Annual poultry industry health checkup

By Lilian Schaer

Features Disease watchLast year was a tough one for poultry health, experts say.

Each year at the Poultry Service Industry Workshop, experts deliver regional poultry health updates. This year’s event included a special avian influenza panel.

Photo: Poultry Service Industry Workshop

Each year at the Poultry Service Industry Workshop, experts deliver regional poultry health updates. This year’s event included a special avian influenza panel.

Photo: Poultry Service Industry Workshop From a poultry health perspective, 2022 will remembered as the year of avian influenza in Canada. But AI wasn’t the only challenge facing poultry producers across the country, noted Dr. Teryn Girard of Prairie Livestock Veterinarians and Dr. Jessalyn Walkey with Production Poultry Veterinary Services in Ontario.

The two veterinarians presented poultry disease updates from Western and Eastern Canada, respectively, at the 2022 Poultry Service Industry Workshop held in Banff, Alta.

“Disease is one of the major things that gets in the way of our production. When it comes to high performance, everything matters, and disease is one of the big barriers to that high performance,” noted Walkey in her presentation. “Health is the difference between stress level and stress threshold and resilience is the capacity to keep performing while facing disease challenge.”

Turkeys

Starvation was the number one commonality affecting meat turkeys in Western Canada. It’s a multifactorial issue, Girard said, caused by issues like poor water quality and availability, poor lighting and barn ventilation problems that keep birds from getting enough feed or water.

Round heart was also reported in Western Canada, usually during the first four weeks of life, with birds suffering from enlarged heart, swollen liver and congested lungs.

“The frustrating thing about this one is similar to starvation in that it could be (caused by) so many things – ventilation, temperature or generics,” Girard said, adding one vet noted improvement by increasing the number of dark hours in some barns to six to eight, from four to six.

The last quarter saw the emergence of colibacillosis in Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta, possibly linked to difficult starts causing immune suppression or water sanitation. As well, a few vets in Alberta and B.C. have been finding coccidiosis outbreaks at four to five weeks of age; in Manitoba, where most turkeys are raised without antibiotics, ongoing challenges include enteritis and E. coli.

According to Walkey, early and late bacterial challenges dominate in Eastern Canada, particularly E. coli, but veterinarians are also reporting enterococcus, staph aureus, necrotic enteritis, gangrenous dermatitis and salmonella. Blackhead and coccidiosis represent additional challenges. In Quebec, reovirus has been an issue, whereas in Ontario, autogenous vaccines have had significantly improved control.

Broiler breeders

Western Canada dealt with high first week mortality this year, caused by supply chain disruptions resulting in chicks arriving on-farm in poor health, early systemic bacterial infections by E. coli and enterococcus, and yolk sac infections.

Egg yolk peritonitis, although stable, was mentioned by vets in three of the four western provinces; E. coli is the primary agent of this problem.

Bacterial lameness is consistently common and seen mostly in males, Girard noted, which suggests excess weight as a cause. Gut integrity could also be a factor, so coccidiosis control may play a role.

“It’s interesting to see how provinces manage coccidiosis differently in breeders – in Alberta, it’s managed more with medication, whereas B.C. relies more on vaccines and in Saskatchewan it’s a bit of a mix,” she said.

Blackhead, although at levels higher than normal, is still low, but has been found in B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan. And management issues continue to pose problems, with three of four western provinces reporting challenges – the biggest being overweight birds, which can lead to femoral head necrosis, staph infections and tenosynovitis.

Bacterial challenges are dominant in Eastern Canada, including early bacterial and pre-lay infections, in-lay septicemia, bacterial lameness in males and salmonella. Vets are also seeing mycoplasma synoviae, mycotic pneumonia and infectious bronchitis virus, of which Delmarva (DMV) is the most common strain. Coccidiosis is stable, but still present, and some cases of intussusception, cannibalism, blackhead and Marek’s Disease are also being reported.

“We’re talking about an amazing amount of bacteria ranging from E. coli to clostridium perfringens to staph – and we’re seeing multi-drug resistant and multi-bacterial infections,” Walkey said, adding that bacterial lameness in males continues to be a problem in Quebec at around seven weeks of age and before or after transfer in Ontario.

Broilers

Yolk sac infection and early or late systemic bacterial infection were reported across Western Canada.

Like broiler breeders, E. coli and enterococcus were the two most commonly cultured bacteria.

“It’s been a tough year for poultry in general with chick shortages and stressed chicks,” Girard explained.

As with broiler breeders, broilers in Eastern Canada are particularly dealing with early and late bacterial infections, led by E. coli but also caused by enterococcus, clostridium, staph, and salmonella.

“E. coli is becoming more complicated; we’re seeing mixed infections and we’re also entering an era of multi-drug resistance,” Walkey said. “It’s both concerning and reassuring to see other provinces documenting this as well.”

Of particular concern is a rise in enterococcus since 2019, particularly in Quebec, and the shift in clinical pattern from kinky back at 28 to 30 days to age to osteomyelitis and septicemia as early as 15 days of age. The good news is that a PCR test for enterococcus is now available through the University of Montreal, she noted.

“Our bacterial profiles and available drugs are shifting. E. coli is highest in chickens, followed by turkeys, broiler breeders and layers and we are seeing the highest concentration of bacteria in yolk sacs, followed by heart and bone marrow,” Walkey said of culture results from her own practice.

On the viral side, inclusion body hepatitis has been the most common cause of high mortality in Ontario with Quebec reporting increases at the end of 2021. Serotype 8b has been the most common strain in both provinces.

Both field and vaccine strains of infectious bursal disease have been major players in Ontario this year, and the industry has been actively increasing screening and on-farm testing. Reovirus is stable to decreasing, with Quebec reporting vertical transmission from U.S.-sourced eggs causing issues between 13 and 21 days of age.

In Atlantic Canada, cecal coccidiosis is top of mind, caused by drug program changes, litter moisture and ventilation challenges. Heat stress also caused issues this year, resulting in mortalities in Ontario and poor growth in Atlantic Canada facilities with inadequate ventilation.

Layers

Egg yolk peritonitis has been stable in B.C. and Saskatchewan but increasing in Alberta, which Girard attributed to possible water quality problems and lack of E. coli vaccine use. Pullet vaccination titres are still an issue, although pullet vaccination has been improving. When pullets coming into production are moved into a layer barn, there can be issues of significant production decrease in the older birds, linked to bronchitis and avian encephalomyelitis.

In B.C., Iinfectious laryngotracheitis has been constant but stable over the last two to three years. Although it spreads and infects easily, mortality is typically low, and recovery is in about one week.

In Eastern Canada, E. coli and other bacteria pose significant problems for layer production. These include early bacterial infections like yolk sacculitis and septicemia, in-lay septicemia, bacterial peritonitis, necrotic enteritis and salmonella. As well, focal duodenal necrosis is common and increasing and infectious bronchitis is reported as severe in non-vaccinated flocks in Quebec.

Atlantic Canada is seeing cases of cannibalism, as well as vets reporting hypocalcaemia and increased starve-outs in a free-run operation.

B.C. floods

The B.C. floods in late 2021 had an impact on all sectors of poultry production in that province. Ten farms in the Fraser Valley were affected, with one farm still renovating almost a year after the event, and general rebuilding is still in progress, including remediation work on the dike and pumping system, and repairs to drinking water and transportation infrastructure.

“It’s been a difficult year for poultry and even though AI has taken over our world, B.C. has been hit really hard and is still dealing with that,” Girard said.

Avian influenza

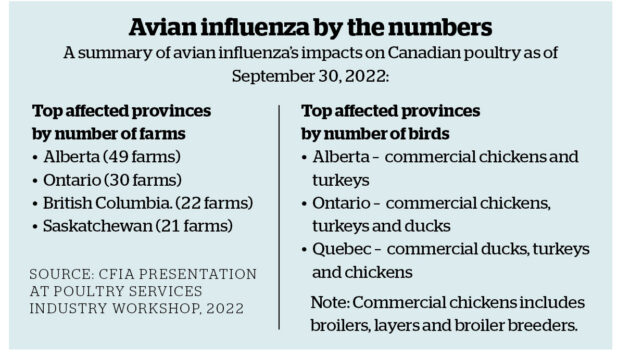

Transatlantic migration of wild birds brought avian influenza (AI) to North America in the fall of 2021. The spike in cases in wild bird populations was soon followed by infections in domestic commercial and small or backyard flocks in Canada and the U.S. in the spring of 2022. After a bit of a lull over the summer months, infections once again trended upwards in the fall.

“When you look at the impacts on poultry in Canada, the total case number continues to increase and we’re seeing a significant number of small flocks affected,” explained Noel Ritson-Bennett, operations manager at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), speaking at the PSIW. “In Western Canada, it came back faster than any of us would have liked to imagine possible. We were hoping for a quieter fall…that doesn’t appear to be the case.”

It’s the CFIA that leads disease outbreak response, and although there have been AI cases in Canada in the past – an outbreak in B.C. in 2004, one infected premise in Manitoba in 2010 and one in Saskatchewan in 2009, for example – this was the first time the agency faced simultaneous outbreaks not just across Western Canada but the whole country.

That broad outbreak pressure, combined with significant travel distances in Western Canada in particular, posed a major challenge for CFIA.

“It is tremendously difficult trying to respond to outbreaks in all four provinces. We don’t have the staff to manage separate incident command centres in all provinces, so we have one command structure and four provincial governments we’re meeting with,” Ritson-Bennett said, adding this makes real-time communications challenging.

At the height of the outbreak in the spring, he estimated CFIA had about 350 of its staff in Western Canada, with some living out of hotel rooms for 60 days or more. And although restrictions were lifting, COVID-19 was also a concern for the response teams on the ground.

Another major challenge was sourcing carbon dioxide for depopulation due to a North America wide shortage of CO2. And even if CO2 was available, trucking it to affected sites was also difficult at times – so much so that, in some instances, scheduled deliveries had to be cancelled as the birds had already died from the virus before the flock could be depopulated, he recalled.

On the positive side, the outbreak has been marked by tremendous support from the industry, including with private veterinarians and staff supporting sampling efforts. Two years of virtual work due to COVID-19 also proved useful, he added, as all the needed infrastructure was already in place, enabling different provinces to work together efficiently.

Disease case studies

Veterinarians across Western Canada track unique cases of poultry disease they encounter in their practices. Here are two particularly interesting examples producers should keep an eye on.

Blackhead in turkeys – B.C. recorded fewer cases of blackhead this past year, although the cases were observed earlier than usual, and a cluster of cases has emerged in the last couple of months.

“This is something to note; as blackhead becomes more common in B.C., we will see it more. We saw it in Saskatchewan last year, so it’s important to be ready in other provinces too,” Girard said.

Morbidity and mortality vary greatly between affected farms in B.C., with some flocks getting really sick and others not as much. Blackhead is a protozoa infection for which there is no real prevention or treatment. Common risk factors include darkling beetles and hot weather.

Infectious bronchitis in layers – In another case, a B.C. producer noticed sub-optimal peak lay level of 90 per cent instead of 97 to 98 per cent, and low production continued after the peak at approximately 80 per cent. Interestingly for a bronchitis case, Girard noted, there was no change in eggshell quality, but during a veterinary analysis, infectious bronchitis California strain was isolated from cecal tonsils.

“That’s a bit scary, as we don’t have a vaccine for that here, so just be aware that it’s out there,” Girard said.

Print this page