Aviary Versus Furnished Cage

By By S. Platz E. Heyn F. Hergt B. Weigl and M.H. Erhard Institute of Animal Welfare

Features New Technology ProductionBehaviour, health and productivity

Groups of 270 Lohmann Silver laying hens each were studied in furnished

cage (FC-S) versus aviary housing (AV-S) systems. In terms of animal

health, egg quality, laying performance ( FC-S 89.4% vs. AV-S 87.0%)

and nest acceptance (> 99%) there was no evidence of a difference

between the two systems.

The behaviour, health and productivity of laying hens in furnished cage and aviary housing systems

|

|

| Comparative studies on behaviour, use of the structural elements offered, as well as health and productive parameters in furnished cage (above) vs. aviary housing systems was studied. Advertisement

|

Groups of 270 Lohmann Silver laying hens each were studied in furnished cage (FC-S) versus aviary housing (AV-S) systems. In terms of animal health, egg quality, laying performance ( FC-S 89.4% vs. AV-S 87.0%) and nest acceptance (> 99%) there was no evidence of a difference between the two systems.

The dust bathing activity of the hens in AV-S corresponded to natural circadian behaviour patterns. In contrast, FC-S hens invariably exhibited incomplete dust bathing patterns on the mat and on the grid floor without any diurnal rhythm. In FC-S 15.6% of all hens used the perches during the light phase vs. 74.9% during nighttime. 26.1% of the hens rested on grid floor in spite of the available perch space 17 cm in width.

Furnished cages

The development of furnished cages was the result of efforts to combine hygienic and economic benefits of cages with animal friendly enrichment of the husbandry environment (e.g., laying nests, perches and dust baths) that enables the animals to achieve hen-specific behaviour patterns. It is important to evaluate the actual welfare status of hens in these novel systems (Blokhuis et al., 2007). This investigation presents the results of comparative studies on behaviour, use of the structural elements offered, as well as health and productive parameters in furnished cage (FC-S) vs. Aviary housing (AV-S) systems.

Study method

Using 540 hens of the Lohmann Silver breed, aged 18 weeks, 270 hens were allocated to six Furnished Cage systems (FC-S, type 715/725, Salmet, Berge), the other 270 animals to three aviary housing systems (AV-S, type natura, Big Dutchman, Vechta). The stocking rate of the three AV-S groups was 90 animals each vs. 45 animals each in the FC-S groups. Each individual animal was provided with 1600 cm2 of useable space (in addition to the nesting area) in the AV-S and 1004 cm2 in the FC-S.

The study examined the question of whether the frequency of nest use correlates with light intensity. Therefore, in each FC-S the hens were offered a bright nesting space located on one side of the barn with an outside light intensity of 193 lx on average, and a dark nesting space on the opposite side with outside 20 lx on average.

In FC-S two Astroturf mats served as sand baths, each with a base area of 1800 cm2, automatically dredged with feed (1000 h, 1200 h, 1400 h; amount of substrate: approx. 35 g). Four low perches ran crosswise to the grid floor and had a length of 125 cm. The distance to the grid floor varied between 13 cm (around the feed chain) and 7 cm (in the middle, around the nipple troughs). Apart from that, two perches with a length of 135 cm were positioned alongside the running area, 22 cm above the grid floor. The total length of the perches was

770 cm.

The three AV-S used were separated from each other by a wire mesh. Along the walls there were eight double laying nests in each compartment with an individual size of 32 x 50 cm, arranged on top of each other in two rows. By direct observation and continuous behaviour sampling in both husbandry systems the frequency of use of the nests for laying eggs and all behavioural elements associated with dust bathing were recorded. Determination of the mortality rate and assessment of the plumage condition by a scoring system of 1 (intact) to 4 (> 144 cm2 of bald skin areas) served as a comparative assessment of the state of health at the end of the study.

Furthermore, the tensile strength of both femur bones was measured post mortem on 36 animals from each husbandry system in a material testing machine (Z005, Zwick/Roell).

Egg weight (n=2405 FC-S, n=2517 AV-S), daily rate of cracked and dirty eggs and eggshell breaking strength (n=420/husbandry system) served as egg quality parameters.

Results

Health Parameters: The cumulative mortality rate in AV-S was 2.9%, vs. 4.8% in FC-S. Pathological examination of 36 hens/housing system resulted in sternal deformities or moderate fatty livers in a range of 45% or 54%, respectively. Breast blisters and lesions occurred in approx. 11% or 8.4%, respectively; salpingitis and inactive ovaries were not observed. Generally speaking, the plumage condition differed between the two housing systems (P < 0.05) and worsened continually in the course of the laying period (FC-S from 1.23 in week 33 to 2.81 in week 69, AV-S from 1.10 in week 33 to 1.87 week 69). Measurement of the tensile strength of bones (n=72/housing system) yielded differences between the housing systems (median FC-S 215.6 N vs. AV-S 227.1 N, P < 0.05).

Productive Parameters: Regarding the overall laying performance, the AV-S group showed a median of 91.7%, vs. 89.5% in the FC-S group. Both groups showed relatively small proportions of mislaid eggs (median 0.28 % AV-S vs. 0.33% FC-S). In FC-S there was a difference between the distributions of eggs laid in nests located at the light (193 lx) vs. the dark (20 lx) side of the barn (28.8% vs. 71.2%, P < 0.001). The median egg weight was approximately the same in both groups (AV-S group 60.95 g vs. FC-S group 60.63 g). The median proportion of broken and cracked eggs was higher (P < 0.05) in the FC-S group, with 1.65% vs. 0.06% in the AV-S group. An overall analysis of the eggshell breaking strength showed differences between the two groups (AV-S 32.87 N vs. FC-S 30.66 N, P < 0.05). The median value of eggshell thickness in the FC-S group was 0.28 mm vs. 0.29 mm in the AV-S group. The FC-S group showed a higher (P < 0.05) portion of dirty eggs (1.06%) compared to the AV-S group (0.06%).

In terms of the chronological course of nest frequentation during the egg -laying period (observation time between 0430 h and 14 00 h) no difference between the two systems could be found. The average daily egg production level was achieved by 1400 h.

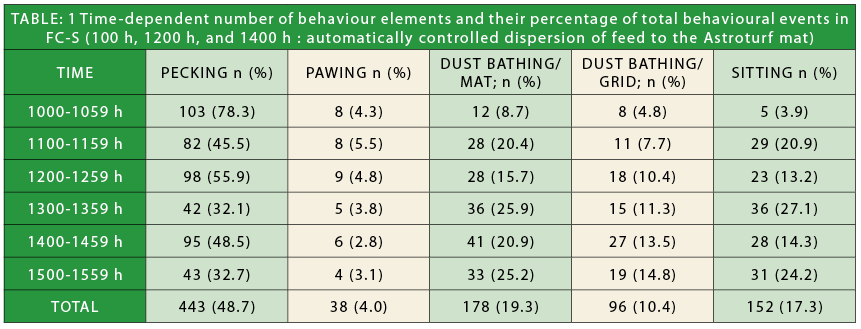

Behavioural Parameters: In FC-S, pecking was the prominent behaviour shown; it occurred more frequently (P < 0.05) following the offer of substrate (98 ffl 4.2 vs. 49 ffl 5.1). In contrast, no correlation existed between the behaviour elements of “dust bathing on Astroturf mats”, “dust bathing on grid floor” and “pawing “, and the offer of substrate (Table 1). Table 1:

|

|

In FC-S all behavioural patterns associated with dust bathing, (pecking, pawing, dust bathing, and sitting) were shown by the hens over the entire period of observation (1000 hñ 1600 h). In AV-S, however, the hens exhibited a diurnal rhythm of dust bathing activities according to natural conditions with a peak level of activity between 1100 h and 1400 h. Regarding duration of dust bathing FC-S group differed significantly to AV-S group (4.77 vs. 14.87 minutes, P < 0.05). Regarding the use of perches in FC-S, significant differences existed between the use during light and dark phase and between the uses of high and low arranged perches. During the light phase an average 15.6% of the hens used the perches compared to 73.3% at night (P < 0.01). 26.7% rested on the grid floor or Astroturf mat during nighttime.

In summary, 67.3% of the hens preferred the lower perches, and 32.7% the higher perches (P < 0.01).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to analyze whether structural elements (nests, perches, and mats for dust bathing) in the system of furnished cages enable laying hens to exhibit typal behaviour while avoiding damage in the technical design offered. Additional parameters regarding health and product quality were evaluated. The study was conducted in comparison with an Aviary system. A high acceptance of the nests, equipped with Astroturf mats, was found in both systems. However, this good acceptance results in a high number of eggs accumulated below the nesting area, so that the eggs may collide with each other resulting in a risk of cracked and pecked eggs. Since > 80% of the eggs were laid in a time frame of 6 h after turning on the light, it is of special importance to have the eggs automatically removed in short intervals during this period. Due to the intentionally different illumination levels of the longitudinal sides of the stall, 71% of the eggs were laid in nests located on the dark (20 lx) side (vs. 29% on the bright side, with 195 lx). This confirms the results of other studies, which state that hens prefer dark places for egg deposition. To avoid an unequal distribution of the eggs laid, which is associated with the danger of cracked eggs, uniform illumination of the hens’ environment within a range of 20 lx must be ensured.

The proportion between high (22 cm, total length 2.70 cm) and low (8.0 cm, total length 5 .0 cm) perches was 1:1.85. The ratio of hens resting at night on the high perches vs. hens resting on low perches was 1: 2 (11 vs. 22) and matches the proportion of the different perch arrangements. The frequency of use of the perches was significantly higher during dark phases vs. light phases. During light phases use varied greatly. An average 15.6% of the hens used the perches, preferring the lower ones. Since these were easy to reach, the danger of being disturbed by other hens increased. Therefore, the perches in this setup fail to meet the hens’ resting requirement. The actual frequency of perch usage during the light phases was considerably lower than the 40-50% stated by Blockhuis et al. (2005). This shows that it is possible to increase perch usage by way of design engineering. However, in spite of increased space offered (17 cm/hen instead of regularized 15 cm/hen) 26.7% of the hens rested at night on the grid floor or the Astroturf mats. Keeping in mind the high motivation of hens to perch (Olsson and Keeling, 2000), it can be concluded that the FC-S in the design studied and the dimensions do not meet the hens’ requirements in terms of typal resting behaviour. The hens’ growing up will increase this welfare-reducing situation. The restricted cage dimensions account for an unfavourable angle of approach, and the possible danger of collision of hens on the perch or cage facilities inhibits the birds’ ability to perch. Hens in AV-S exhibited a circadian rhythm of dust bathing activity with peaks between 1100 h and 1400 h. Hens in FC-S, in contrast, showed all behavioural elements associated with dust bathing independently of time throughout light phases, which does not reflect natural housing conditions (Lindberg and Nicol, 1997).

In the study, pecking was the predominating piece of behaviour, which can be explained by the nutritive character of the substrate offered. Due to the restricted area and offer of suitable substrate for dust bathing as well as the optical stimulus of dust bathing hens (Duncan, 1998) a large number of hens exhibited dust-bathing behaviour at the grid floor of the cage. This is interpreted as an activity, which is not suitable to reduce the motivation of dust bathing (Olsson et al., 2002).

With regard to the multitude of consecutive behaviour patterns within the scope of dust bathing behaviour (van Liere and Wiepkema, 1992), the lack of adequate possibilities to perform typical dust bathing behaviours in FC-S is a point worth mentioning. This conclusion is supported by the absence of a circadian rhythm as observed in AV-S.

Generally speaking, comparison of health and productive parameters resulted in minor differences. Due to the constricted space and reduced mobility, hens in FC-S exhibited a significant inferior plumage condition and lower tensile strength of the femur bone. However, no difference could be found regarding mortality rate and results of post-mortem examination. Considering that the hens were not beak-trimmed the mortality rates of 4.8% (FC-S) vs. 2.9% (AV-S) must be considered satisfactory. Even though comparison with regard to health and egg quality does not yield any serious disadvantage of one system over the other it has to be taken into consideration that normal behaviour is restricted in FC-S.

- Blockhuis, H.J., Finks van Niekerk, T., Bessei, W., Elson, A., Guemene, D., Kjaer, J.B., Levrino, G.A.M., Nicol, C.J., Tauson, R., Weeks, C.A. and van de Weerd, H.A. (2007). World’s Poultry Science Journal, 63: 101-113

- Duncan, I.J.H. (1998). Poult. Sci. 77: 1766 – 1772.

- Lindberg, A.C. and Nicol, C.J. (1997). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 55:113 – 128.

- Olsson, I.A.S. and Keeling, L.J. (2000). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 68: 243 – 256.

- Olsson, I.A.S., Keeling, L.J. and Duncan, I.J.H. (2002). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 76: 53 – 64.

- van Liere, D.W. and Wiepkema, P.R. (1992). Anim. Behav. Sci. 43 549 – 558.

- Weeks, C.A. and Nicol, C.J. (2006). World’s Poultry Science Journal, 62: 296 -307

Print this page