Biosecurity

By Agriculture and Food Innovation Network (AFRI) and Matt Richardson

Features Barn Management ProductionWho – and what – can make a difference

Since the avian influenza outbreak in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley

in 2004, and each time another incident is recorded (most recently in

turkeys in the U.K. ) the B-word continues to make headlines. What

could have been done? Who should have done it? What impacts have been

felt?

Since the avian influenza outbreak in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley in 2004, and each time another incident is recorded (most recently in turkeys in the U.K. ) the B-word continues to make headlines. What could have been done? Who should have done it? What impacts have been felt?

The Food and Agriculture Organ-ization of the United Nations has a 100-word definition of biosecurity which can be summarized as “preventive measures for the management of invasive alien species, genotypes and viruses that threaten livestock, poultry and plants and that can have adverse consequences for human health.”

The truth is, biosecurity is not broadly practised, yet, and in Britain’s recent turkey case, no one can agree on what went wrong. How did the outbreak occur? Who will pay the costs? Will the consumers turn against the product?

In case you haven’t heard, good things are happening across Canada, as the poultry sectors put risk management strategies into place.

Threatening diseases

Over 30 diseases have “emerged” over the past three decades, including SARS, BSE, HIV and AI, which pose severe threats to human health and have already caused significant economic losses in Canada.

In poultry and livestock, according to Ottawa virologist Ed Brown, high-intensity rearing creates a perfect environment for invasive, virulent viruses. A United Nations task force recently identified farming methods that concentrate birds into contained spaces as a primary cause of the bird flu epidemic. Brown points out that although bird flu can spread among free-range flocks by contagious migrating birds, wild bird viruses pose a severe threat only once they enter a high-density operation.

In all cases, the message is the need for integrated action to bolster Canada’s defences. That is why government and industry are working co-operatively to establish programs at all four stages of foreign animal disease “management,” Prevention, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery.

Prevention

Federal and provincial government bodies and livestock and poultry organizations share the responsibility for safeguarding human and animal health by implementing effective preventive measures, both on farms and among the agribusinesses that service them.

Practices that have proven effective in Canada and elsewhere are being incorporated into on-farm food safety plans, or established as free-standing programs like the recent compulsory biosecurity program in British Columbia. Protocols for farm service personnel are being readied for implementation in several areas of the country. CFIA has convened an industry body from across Canada to look at national standards for avian biosecurity.

Prepardness

The Poultry Industry Council, together with the Ontario Livestock and Poultry Council (OLPC), have worked for several years to improve the preparedness of their industry sectors in Ontario. The knowledge that has been developed through a series of annual simulation exercises, first in poultry, and now in other livestock sectors, has been shared freely across the country. Similar exercises are underway in the poultry industry in British Columbia, Quebec, the Atlantic provinces and elsewhere, as a key step in generating discussion and action to prepare for a possible outbreak of significant animal disease.

Organizations like these can act as catalysts to achieve joint action among governmental bodies, producer and service organizations to effect the necessary improvements in biosecurity risk management practices.

Response

Simulations have also provided valuable inputs to response planning, and reviews of “Lessons Learned” from the B.C. outbreak have focused industry efforts on what is most effective, and who needs to be involved. Following the disease simulations in the poultry industries in Ontario, a “Feather Board Command Centre” was formed representing the four poultry boards. This Centre will direct the first-line response when a suspected disease has been identified. The FBCC remains on the job until the incident is dealt with.

Recovery

Recovery requires action in two areas – how quickly can the affected units be back in business, and how are the product losses and costs of cleanup and restart minimized and offset. Poultry boards are investigating which activities and protocols could lead to faster cleanup and repopulation following a disease event. Methods of disposal, including new composting techniques, are researched and utilized.

Private sector insurers

Losses stemming from the 2004 outbreak in the Fraser Valley reached approximately $400 million. Compensation under government programs for lost flocks, the only coverage available to the industry at that time, totalled approximately $60 million, leaving producers and their industry partners exposed to the balance of costs for cleanup, re-establishment of their businesses, and loss of income.

Under OLPC leadership, with funding from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, work is underway to determine whether disease-loss insurance, provided by the private sector, and working in a co-ordinated fashion with government-managed compensation programs, could be successfully launched in Canada.

Initial review of biosecurity and related farm practices on a number of livestock farms across Ontario provided a basis for further study. Statistics on disease experience and industry practices are now being collected and analyzed for use in designing insurance products that could be ready for use in Ontario by the late fall of 2007. If they are successfully implemented in Ontario, they can then be made available across the country.

For private sector insurers to provide disease cover, they first require exposure measurement and assessment of conformance to acceptable preventive standards by individual farmers. Government organizations, re-insurers, insurers and commodity groups will require independent, certified proof of farmer conformance to accredited biosecurity programs.

The outcome will be a win-win for everyone. Better biosecurity means less risk of disease. This will protect Canadian businesses and consumers. The government and industry will be effectively managing risk as committed partners with common goals.

Producer Commitment

Canada already has very good on-farm food safety programs for some species of livestock and poultry, many of which have recently added biosecurity elements. Voluntary programs are becoming mandatory. However, variation in producer adherence to these existing programs remains an issue. Variation from livestock sector to livestock sector is also evident.

Analysis of on-farm risk management data samples in the OLPC studies have identified variation between the best and poorest performers of some 40 per cent. Clearly, with the variation in these findings, some producers are more concerned about biosecurity than others. Some are voluntarily implementing procedures to improve their risk profile; others are not so diligent. Should we be working to improve the performance of the lower-performing participants? Are those who are working diligently wasting their time until all producers, and their service sector suppliers, are meeting minimum standards?

Past-PIC chair and current chair of OLPC’s Insurance Committee, Deborah Whale, is undaunted by the complexity of working across a multitude of organizations to achieve a common goal. She brings a great deal of knowledge of the industry and government infrastructure as well as experience as a successful farmer. She concludes that, “the fact that Canada’s defences against major disease outbreaks are only as strong as the weakest link has made me only too aware that no single government or industry body can be left in isolation to do its own thing. We stand or fall together on this one.”

In a fascinating display of statistical analysis, OMAFRA’s Bruce McNab, working together with CFIA’s Caroline Dub, demonstrates the overall industry effect on the patterns and extent of disease spread under different assumptions of participant variability. In simplest terms, consistent performance in biosecurity among producers in a region, will result in a relatively even spread among farms, all other things being equal.

In addition, the expected outcomes of four scenarios of variability, measured in overall risk of spread among a series of farms, are included in his work.

What becomes clear is that the industry’s risk – our overall risk – can be substantially reduced by success in implementing an industry-wide program that is universally adopted and that brings the risk profile of all participants to a lower level (b and c in Figure 1, page 36.) However, it is also clear that the actions of one lower-risk producer in a related chain of participants (d in Figure 1) even if there are high-risk participants in the same chain.

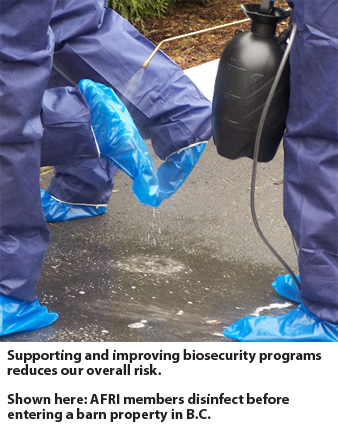

So, working to support and improve those willing participants in their biosecurity programs improves our overall risk.

The evidence strongly suggests the need for compulsory national biosecurity standards for farms and the service sectors. The better our risk management, the more secure the livestock and poultry industries will be. The biosecurity of the industry is only as strong as its weakest link.

Deborah Whale is right, and is supported by Dr. McNab’s analysis. Improving our worst performers is absolutely necessary. Individually, they represent the most significant risk to infection of other farms with whom they are linked – either by supply, or by common service-personnel visits. This is a tough assignment.

But the other conclusion of Bruce McNab’s work is a good-news story. Individual growers who commit to and achieve good biosecurity performance, and thereby reduce risk of disease transmission, will have a positive impact on the probability of transmission throughout the community, despite slow-adopting neighbours.

Yes, effective risk management will contribute to a more bio-secure industry – and that means fewer losses to disease, and lower insurance rates.

Several of the ‘holes in the biosecurity blanket’ were identified in the services sector. Service providers such as feed and fuel suppliers, barn cleaners, equipment sales and services, and many others, travel between farms frequently. Many have inconsistent biosecurity practices – others have none at all. And in their day-to-day activities they are a potentially leading carrier of foreign animal disease.

In the 2005 project, led by Jim Pettit, DVM, for the Poultry Industry Council, a team of consultants at eBiz Professionals of Guelph, Ont., set out to establish a consistent set of biosecurity protocols for use by the services sector. Its goal: to reduce the spread of foreign animal disease among the farms it serves. Funding for the work was provided by the Private Sector Risk Management Program of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

The project team worked directly with service sector organizations, to document their activities before, during and after a farm visit, and to identify all of the possible contamination and transfer points for disease. The goal was to learn from the working groups what standards could be set that all participants could implement, to help in preventing the spread of disease. The meetings continued for the better part of a year, and have resulted in the publication of more than a dozen protocols that each service provider can follow. In fact, all of the protocols and related information are freely available on a website developed for the purpose – www.agbiosecurity.ca. n

Print this page