Biosecurity and avian influenza

By Lilian Schaer

Features Disease watch avian influenza H5N1Experts from different provinces discuss the role of biosecurity in Canada’s outbreak this year.

Experts say diligent attention to biosecurity helped lessen the impact and minimize the spread of avian influenza in Canada during this year’s outbreak.

PHOTO CREDIT: Egg Farmers of Canada

Experts say diligent attention to biosecurity helped lessen the impact and minimize the spread of avian influenza in Canada during this year’s outbreak.

PHOTO CREDIT: Egg Farmers of Canada It’s not over yet, and already 2022 will be one that Canada’s poultry industry is unlikely to forget. It’s the year that brought the latest outbreak of Avian Influenza (AI) to Canada, affecting farms and flocks across the country as well as wild bird populations.

Despite its scope and severity, the crisis could have been much worse. A combination of industry-wide preparedness, earlier outbreaks in Europe tied to migratory bird patterns, and in particular, diligent attention to biosecurity all combined to lessen the impact and minimize the spread in Canada.

We checked in with a few industry experts across the country for their perspectives on the outbreak, particularly with respect to biosecurity.

Dr. Tom Baker is Manager and Incident Commander of Ontario’s Feather Board Command Centre, which coordinates poultry industry emergency response to disease outbreaks. Dr. Tom Inglis is the founder and a managing partner of Poultry Health Services Ltd. in Airdrie, Alberta. Dr. Luke Nickel leads Poultry Health Services’ operations in British Columbia from his base in Abbotsford. Dr. Gigi Lin is a veterinarian with Canadian Poultry Consultants Ltd., also based in Abbotsford, B.C.

What was the scope and scale of Avian Influenza in your province?

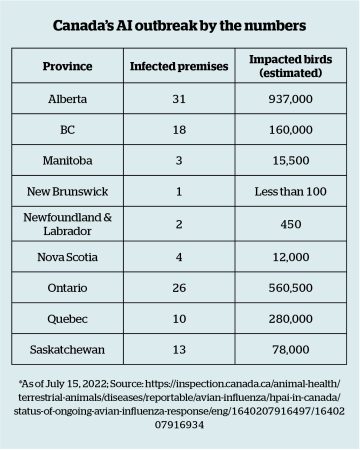

Baker: Compared to 2015, when AI last hit Ontario, this outbreak was more intense and extensive, stretching in clusters from the southwestern tip of the province to the Quebec border. Twenty-six flocks were infected compared to only three in 2015, with wild birds playing a key role. About 23% of affected Ontario flocks were backyard flocks, which is a significant difference from 2015, and we had quite a diversity of flock types affected, particularly ducks and geese. Our last case was on May 18, and recovery is well underway in terms of virus elimination.

Baker: Compared to 2015, when AI last hit Ontario, this outbreak was more intense and extensive, stretching in clusters from the southwestern tip of the province to the Quebec border. Twenty-six flocks were infected compared to only three in 2015, with wild birds playing a key role. About 23% of affected Ontario flocks were backyard flocks, which is a significant difference from 2015, and we had quite a diversity of flock types affected, particularly ducks and geese. Our last case was on May 18, and recovery is well underway in terms of virus elimination.

Inglis: We had the greatest number of cases and birds infected and destroyed in Alberta. We hadn’t seen highly pathogenic Avian Influenza in domestic poultry in Alberta for several decades, so it was new for us to be the centre of the majority of activity. The spread was from wild birds, and we had unrelated outbreaks in different regions. We spent more time talking about aerosol spread instead of infection entering the barn on people. The outbreaks were across the province and across commodity groups, with a mix of commercial farms and backyard flocks.

Inglis: We had the greatest number of cases and birds infected and destroyed in Alberta. We hadn’t seen highly pathogenic Avian Influenza in domestic poultry in Alberta for several decades, so it was new for us to be the centre of the majority of activity. The spread was from wild birds, and we had unrelated outbreaks in different regions. We spent more time talking about aerosol spread instead of infection entering the barn on people. The outbreaks were across the province and across commodity groups, with a mix of commercial farms and backyard flocks.

Lin: It’s been unprecedented not only in Canada but globally with so many cases. Our practice got the first case in B.C. in April; we were lucky the first case was not in a dense commercial poultry area. We had a total of 18 cases in B.C., with four in commercial flocks and the rest in small flocks. It was not as bad as it could have been.

Lin: It’s been unprecedented not only in Canada but globally with so many cases. Our practice got the first case in B.C. in April; we were lucky the first case was not in a dense commercial poultry area. We had a total of 18 cases in B.C., with four in commercial flocks and the rest in small flocks. It was not as bad as it could have been.

Nickel: We’ve had AI challenges in B.C. in 2004 and in 2014, so most producers are up to speed on the consequences of poor biosecurity and what that can cause. The B.C. industry moved to a red biosecurity status before we had any confirmed cases here and that helped us get ahead of it.

Nickel: We’ve had AI challenges in B.C. in 2004 and in 2014, so most producers are up to speed on the consequences of poor biosecurity and what that can cause. The B.C. industry moved to a red biosecurity status before we had any confirmed cases here and that helped us get ahead of it.

What tools or approaches were used to try to contain the outbreaks in general?

Baker: Collaboration between government agencies and industry was key. This was very well done with a lot of communication like webinars with small flock growers and daily updates on calls with industry, which really helped keep awareness up. You can’t control what flies overhead but you can protect your flock and take steps to do so.

Inglis: We were looking at dead bird surveillance as a primary tool as opposed to swabbing all the flocks, which was a major improvement. Producer-collected samples let people test on-farm, and with smaller samples we didn’t use as many resources that were in shortly supply. The testing was also more accurate; we were finding AI more in dead birds.

Lin: Our biggest challenge was that our provincial laboratory had been damaged by the flood last November and it was still closed in April. I must give so much credit to the industry, especially the leaders running the Emergency Operations Centre for the four feather boards in B.C. The conversation started last fall to get all the vets together on AI and prepare, and we went to red level biosecurity before we had a confirmed case in B.C.

Nickel: A lot of practical things were done like setting up extra disinfection areas for vehicles coming on-farm and people going in and out of barns, minimizing the amount of movement between sites and not sharing equipment, for example.

How big a role did biosecurity play in management of the crisis?

Baker: We knew this outbreak was coming so we discussed ahead of time and agreed that we would call for heightened biosecurity across Ontario the first time we saw a suspect case in any domestic poultry flock. We activated that on March 26 with a list of measures and we think that it definitely played a role in preventing spread. Everything contributes; there is no single tactic but the system as a whole works together.

Inglis: I’ve been teaching and working on biosecurity for my whole career and the hardest thing is you never know how bad it could have been, you never know what you could have prevented. Nothing beats real experience, but we’ve done exercises, so we were as good as we could be even though geography is pretty punishing here with the population so spread out.

Lin: It was huge. AI is a contagious disease and with resources so stretched with outbreaks in many provinces, biosecurity is what keeps the virus from going elsewhere. It also helps in dealing with a confirmed outbreak, from how to handle manure to how to deal with culls.

Nickel: It played a major role and was quite successful at minimizing the number of commercial farms infected. People took what industry and vets were telling them seriously and followed precautions. Even little things make a difference, especially in B.C. where farms are so close together. That’s why biosecurity is even more important here.

Which biosecurity practices were found to be most successful and why?

Baker: Most critical is separating flocks from direct or indirect exposure to a contaminated environment. Even if you don’t see wild birds, they may have been there and in cool, wet weather, the virus hangs around. When you think about the possibilities for exposure, that gives a bit more motivation for proper compliance with the measures and you can break that cycle of exposure.

Lin: There isn’t one thing, it’s a combination. I always recommend clients make a checklist for biosecurity that is relevant to their farm; it makes biosecurity more practical and reminds you of what needs to be done to keep disease away from the premise, not just the flock. One factor we can’t control is the natural environment, like wind direction, rain fall, or topography for water drainage, so we have to adjust for that to minimize what is coming into the barn. It’s more complex than just shutting the barn door.

Nickel: It’s everything together. For example, even if you’re the best handwasher but you don’t change your boots, the system can fall apart. The biggest lesson is to make sure you are thinking through why you do things and don’t be in a rush. Try to keep up the practices you’ve learned even after the outbreak. Even if it seems as though biosecurity is a small thing and there are bigger issues at play, it becomes a big issue if your flocks gets the disease.

Looking ahead to the next one

Official industry and government debriefs are still underway, but few early “lessons learned” include:

- Keeping biosecurity front and centre, including through regular refreshers for everyone in the industry

- Adding air flow and filtering to future biosecurity considerations

- Industry staying mobilized and aware of potential risks

- More timely, detailed and transparent communication

- Allocating more resources and surge capacity, especially with veterinarians

- Supporting routine surveillance work and epidemiological studies to boost understanding of AI

Print this page