Housing Hens to Suit Their ‘Needs’

By T.M. Widowski University of Guelph and P.H. Hemsworth University of Melbourne

Features Business & Policy Consumer IssuesExamining what the research shows about behavioural priorities versus needs in layers

Some of the most difficult issues concerning the welfare of hens in

conventional cages have to do with behavioural restriction; namely the

lack of opportunities for hens to perform the following behaviours:

Some of the most difficult issues concerning the welfare of hens in conventional cages have to do with behavioural restriction; namely the lack of opportunities for hens to perform the following behaviours: nesting, dust bathing, foraging and perching. The term behavioural ’need’ was coined over 20 years ago to refer to specific behaviour patterns that may be important for hens to perform and that, when prevented, would result in frustration or some negative psychological state that would cause suffering and impair welfare.1

|

| What hens need: The concept of behavioural “needs” in hens is difficult to define and provide evidence for. So far, studies demonstrate that the ability to nest prior to laying an egg is of higher priority to a hen than other behaviours. Advertisement

|

This concept of behavioural “needs” has been debated because of the difficulties in defining it and in providing evidence for it. 2 Preference tests have been used to identify resources and behaviour that might be important to hens.3 Some studies of motivation identify internal factors (i.e. changes in hormones or physiological state) and external factors (i.e. external stimuli or changes in the environment) that cause the behaviour to occur, while others measure how much a hen is willing to work in order to access a resource that allows her to perform the behaviour under different physiological or environmental conditions.

Deprivation of a specific behaviour is generally considered to be more likely to reduce welfare when the factors motivating the behaviour are primarily internal and when the performance of the behaviour itself rather than its functional consequences are important to the hen.4 Researchers have suggested that behavioural “need situations” or behaviour associated with intense negative emotions likely evolved for those behaviours where immediate action is necessary to cope with a threat to survival (e.g. dehydration or escape from a predator) or reproductive fitness (e.g. nesting).5

Recently, the term “behavioural needs” is being used to refer to “(instinctive) behaviours that are performed even in the absence of an optimum environment or resource,” and the term “behavioural priorities” refers to behaviour (or resources that accommodate the behaviour, for example a nest box or litter) that animals are willing to work for.6-7 It’s been suggested that while nesting was a behavioural “priority,” dust bathing, foraging and perching were all behavioural “needs”.6-7 Lack of opportunity to perform each of these specific behaviours are considered equally to be risks to welfare in conventional cages.7

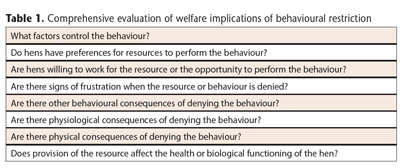

However, any argument for impaired welfare due to restriction of such behaviours would be strengthened by supporting the physiological measurement of frustration, or evidence of decreased health or increased physiological stress.3,8 In the case of both nesting and dust bathing, most research has focused on motivation with little attention paid to the physiological consequences of deprivation. Therefore a more comprehensive approach to evaluating the welfare implications of deprivation of these specific behaviours should consider the quest ions listed in Table 1. In the following sections our current knowledge with regard to these questions is reviewed for nesting and dustbathing.

NESTING

Nesting is elicited by the endocrine events associated with ovulation and presumably evolved with strong links to reproductive fitness. Most hens prefer to lay their eggs in enclosed nest boxes, and the strength of hens’ motivation to access a nest box has been demonstrated in a variety of ways.3,6 Hens have been shown to be willing to squeeze through narrow gaps, push open weighted doors, and pass through cages occupied by unfamiliar or dominant hens in order to gain access to a nest box; these tasks are normally considered to be costly or aversive to hens.

|

When denied access to a nest box, hens are more active, take longer to settle before laying their eggs and perform what has been described as stereotyped pacing.9,10 Researchers have reported a significantly higher frequency of “gakel calls” when hens were “thwarted” from nesting by removing them from nest boxes during the sitting phase of pre-laying behaviour.11 However, this same call, also referred to as the pre-laying call, is typically given during the searching phase of prelaying behaviour when hens are housed in floor pens with nest boxes.12 Therefore it is difficult to conclude whether this vocalization reflects frustration within the context of nesting.

A range of environmental and psychological stressors has been shown to cause delays in the expected time of oviposition with consequent effects on egg shell quality.13 Delayed oviposition is due to retention of the egg in the shell gland (uterus) which is caused by the release of adrenaline. A change in egg shell colour or quality can be used as an indirect measure of delayed oviposition because additional time in the uterus after the cuticle on the egg has been laid down can result in a deposit of extra-cuticular calcium. Oviposition is delayed when the sitting phase of nesting is disrupted.14,15

Surprisingly few studies have used either direct or indirect measures of delayed oviposition or other physiological measures to compare the responses of hens in housing systems with and without access to nest boxes. Recent work by Cronin and Barnett (personal communication) showed that hens with nest boxes laid their eggs earlier in the day at 24 and 30 weeks of age compared to hens in without nest boxes, but this difference was no longer significant after 30 weeks. However, a different study found that eggs from hens in cages without nest boxes, or blocked from using a nest box yielded the same amount of extracuticular calcium as eggshells from hens that were able to lay their eggs in the nest when sampling from 28 through 44 weeks of age.10

In an experiment examining the effects of nest boxes concluded that while 60-80 per cent of hens consistently used the nest box, there were no long-term adverse effects of denying hens access to a nest box on their stress physiology.16 Another study concluded that any effects of nest boxes (and dust baths) on hen welfare were smaller than effects of group size and space allowance, although such furniture, when present, was generally well-used.17

DUST BATHING

Dust bathing is stimulated by a combination of internal and environmental factors.

When birds have been kept without substrate for dust bathing, the latency to dust bathe is shortened and they perform longer and more intense dust bathing.3The sight of a dusty substrate, ambient temperature, light and a radiant heat source also affect hens’ tendency to dust bathe.18,19 External factors can be potent stimuli for dust bathing and the behaviour can essentially be “switched on” under the right conditions.

Groups of birds often perform dust bathing simultaneously, indicating that the behaviour may be socially facilitated, but the role of social factors in a hen’s motivation to dust bathe is still unclear.19,20

Hens prefer to dust bathe in substrates with small particle sizes, but a variety of operant and obstruction tests have shown that hens are not very willing to work for a dust bath. 3,21,22 In furnished cages when an area of litter or sand substrate is provided, a large proportion of hens are observed to perform dust bathing on wire floors, with most of this “sham” dust bathing occurring near the feeder.23

There is very little evidence that hens experience frustration when deprived of dust bathing in substrate. Stereotyped pacing, head flicking or displacement preening has rarely been reported in studies on deprivation of dust bathing. Researchers in one study have reported a higher number of gakel calls during tests aimed at thwarting dust bathing but they also observed significantly less pacing and no differences in escape attempts, alarm cackles or displacement preening during the period of “frustration” compared with “pre-frustration” conditions.11

Few studies have specifically examined the stress response or changes in other physiological measures associated with dust bathing deprivation. No differences between hens in furnished cages with or without dust baths on plasma corticosterone or measures of immune response has been shown.24 To date, the only functional consequence of the absence of dust baths that has been clearly demonstrated is a significantly higher concentration of lipids on the feathers of hens in conventional cages compared to hens housed on litter.25

CONCLUSIONS

While studies of motivation can provide compelling evidence that the performance of some behaviours may be important to the hen, additional evidence, particularly on occurrence of abnormal behaviour, stress physiology and health, is necessary to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of restricting some behaviours on welfare. This is especially important when provision of resources to accommodate behaviour may result in “trade-offs” for other aspects of the hen’s welfare, such as health or hygiene.

Full references are available at www.canadianpoultrymag.com . Click on “current issue” to find this article. Presented at the XXIII World’s Poultry Congress.

Print this page