Chick culling alternatives

By Melanie Epp

Features Emerging TrendsIn-ovo sexing and dual-purpose breeds present challenges and opportunities.

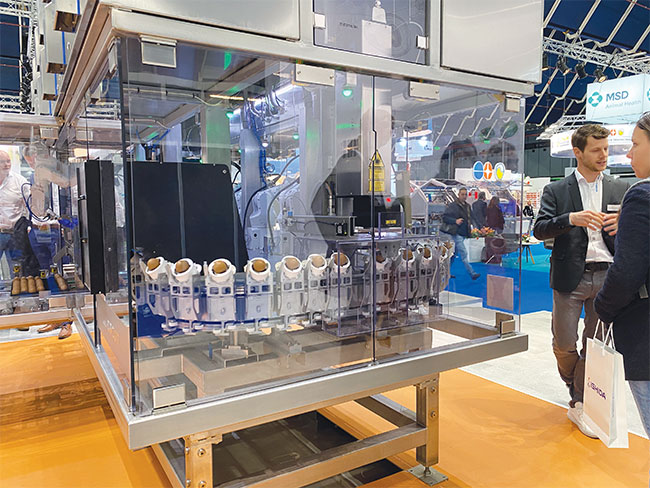

Developed in Germany, Seleggt, displayed here at VIV Europe in June, sexes eggs using hormone-based gender identification.

PHOTO CREDIT: Melanie Epp

Developed in Germany, Seleggt, displayed here at VIV Europe in June, sexes eggs using hormone-based gender identification.

PHOTO CREDIT: Melanie Epp Globally, it’s estimated that the layer sector culls 6.5 billion male chicks each year. In Europe, the culling of day-old chicks has become a politically contentious issue that has promoted policy change in various countries.

While some solutions show promise, others have little environmental, economic or ethical basis. In Germany, for instance, policymakers have been accused of putting the proverbial cart before the horse. A panel of experts gathered at VIV Europe in June to discuss the options: sex determination technology; the raising of male layers; or switching to dual-purpose breeds.

This year, chick culling has or will become illegal in several European countries. Under German legislation, it was banned in January 2022, and it will be banned in France by the end of 2022. Discussions are ongoing in other European countries, including Austria, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Three solutions have been proposed to end the practice: raise dual-purpose birds; raise male hens; or adopt technology that determines sex in-ovo. For the latter, several solutions are either on the market already or on the horizon.

In-ovo sexing technology

Dutch hatchery equipment company HatchTech is co-owner of two technologies: Seleggt and PLANTegg. Carla van der Pol, head of research and development at HatchTech, explains how they work.

Developed in Germany, Seleggt sexes eggs using hormone-based gender identification. Lasers create a 0.3 millimetre hole in the shell of the egg and extract a small amount of allantoic fluid. The allantoic fluid of a female hatching egg contains estrone sulphate, a female hormone. That fluid is placed into a patented marker where it changes colour if estrone sulphate is present. The eggs are sealed after extraction and sorted according to results. Seleggt can sample one hatching egg per second or 3,000 eggs per hour.

It’s designed for 24-hour use and has been on the market since 2018.

Also developed in Germany, PLANTegg uses a small needle to remove allantoic fluid, which is analyzed using PCR technology for gender chromosomes. Once sampled, they are sealed and sorted, and the female eggs are returned to the setters to continue the hatching process. Sex determination is completed in 1.5 hours. PLANTegg says it is 98 to 99 per cent accurate.

Both Seleggt and PLANTegg are in operation in Europe. At the time of her talk in June, Van der Pol said seven million hens had been hatched using the two technologies. Table eggs from these hens are available at 10 different retailers.

“The demand for these eggs at the moment is in Germany, but also in the Netherlands and France,” Van der Pol said. “But there’s upcoming awareness all over Western Europe.”

In the short-term, HatchTech would like to further improve and industrialize the systems to increase the number of hatcheries using them.

“If we can move to an earlier day of incubation that would be preferable for us, both from an ethical perspective, but also from a capacity perspective,” she said. “If you could already analyze your eggs at day zero, you don’t have to incubate any male eggs, and you only have to use half your incubators.”

Currently, German law requires eggs to be sexed by day seven, but there is talk of pushing that to day six. Currently, there is no technology that can determine sex by day six, though.

As HatchTech moves towards day six detection, Van der Pol said they’re facing technical challenges. Eliza and mass spectronomy technology could test allantoic samples at day six, but some improvements are needed to detect hormone levels, as they can be much smaller at this stage of development. PCR tests also work at day six, Van der Pol added, but some compromises will need to be made in terms of cost-price effectiveness and accuracy.

Overall, the researcher sees a bright future for in-ovo sexing technology. “As these technologies become even more streamlined and cheaper, you will see a big advantage in production capacity in the hatchery,” she said. “There will also be economical benefits to using these technologies but we do have to go through these periods of development to get there.”

Another option is Dutch company In Ovo. Co-founded by Wouter Bruins, it has developed a high-throughput screening machine called Ella that samples at very high speed. Using a tiny needle, Ella obtains a fluid sample, and screens the sample for a specific bio marker using Echo mass spectrommetry technology. In less than a second, the gender of the egg is determined. The eggs are stamped and male eggs removed from incubation. This machine currently operates in-line in a commercial hatchery in the Netherlands.

In May of this year, Orbem and Vencomatic Group announced they’re working in partnership to market “Genus Focus”, a fully automated, end-to-end system for sex determination. Using non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Genus Focus determines sex between day 12 and 13 and has a throughput of 24,000 eggs per hour. Two installations with the capacity of 6,000 and 12,000 eggs per hour will be fully operational in France by January 2023.

Pedro Gomez, co-founder and CEO of Orbem, said the technology offers four key advantages: it is safe for eggs and operators; it works with all breeds and egg colours; it’s fast; and, lastly, it’s 96 per cent accurate.

“The big advantage of this setup is that it can be scaled modularly,” said Gomez, adding that their aim is to sex earlier than 12 days. “We believe the earlier, the better, as long as it doesn’t hinder performance.”

Other solutions

Other solutions have been to grow out the male layers or adopt dual-purpose breeds. Peter van Horne, poultry economist from Wageningen University & Research, evaluated both the environmental footprint and economic cost of adopting these solutions in the Netherlands.

There are some 33 million layers in the Netherlands. Sixty per cent of eggs produced are exported, 80 per cent of which goes to Germany. The culled male chicks are not disposed of as waste. Instead, hatcheries receive a small revenue by selling them to zoos, falconers and pet shops as feed.

“It’s a useful destination at the moment, and there are no welfare issues [with culling],” Van Horne said.

If Dutch farmers were forced to switch to dual-purpose production, by Van Horne’s calculations, the industry would require 39 million hens to produce the same number of eggs as the highly productive commercial breeds they would be replacing. The transition would cost the industry an additional €286 million, he said, especially as male layers require 10 per cent more feed.

“My conclusion is the lowest cost to produce eggs is with modern layer breeds,” Van Horne said.

Field data from the Netherlands reveals further inefficiencies in male layer production. It takes 98 days for a male layer to reach 1.5 kilograms. Once mature, they have approximately 17 per cent breast meat and a feed conversion rate of 3.5.

Conversely, broilers take just 42 days to reach a live weight of 2.4 kilograms. They have 25 per cent breast meat and a feed conversion rate of 1.6. At current feed prices, Van Horne estimates an additional cost of €4 per male layer.

Then there’s the question of how to market the end product.

“What do you do with this bird?” asked Van Horne. “Nobody wants it.”

Dutch slaughterhouses have offered four cents per kilogram for layer males, which is even lower than what is paid for spent hens. To meet rising costs, egg prices would need to be lifted one to 1.5 cents per egg, he said. Some companies have further processed male layers into sausage and chicken burgers, but there is no real market demand for these products.

“Consumers will have to pay for this,” Van Horne said.

Sex determination comes with additional costs as well. In-ovo testing requires equipment to sample and separate, plus the additional cost for disposal of male eggs. Including some margin for error, Van Horne estimates it will cost an additional €3.30 per bird, which is similar to the cost of growing out male layers.

But given current feed prices, the cost of growing out male layers would actually be much higher than adopting technology for sex determination, he said.

Van Horne also looked at the environmental cost of switching to male layer production, calculating for regular feed use, land use and energy consumption. He found the carbon footprint of layer males to be three times that of broilers.

“It’s very clear there is a negative carbon footprint,” he said. “It’s also very clear, looking at the environment, that this is not the way to go.”

From economics to ethics

There has been much discussion around the ethics of culling embryos based on whether or not they feel pain. Eddy Decuypere, professor emeritus at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and Wageningen University & Research in the Netherlands, is a neurophysiologist who works with chickens. He discussed the ethical questions around pain reception in embryos at the different stages of development.

The brains of chick embryos develop slowly, Decuypere said. At day 15.5 to 16.5, he said, embryos show high rates of movement, but no higher brain activity. By day 16.5 to 17.5, the first signs of higher-brain activation appear with decreasing movement rates as development progresses. By day 17.5 to 18, all embryos have higher brain activation, and by day 18 to 21, different brain patterns (waking, REM and NREM) begin to emerge.

Pain and suffering from pain can only be present when consciousness is developed, and in chicks, brain function is active at 80 to 90 per cent of embryonic development, Decuypere explained. On the question of moving to earlier and earlier detection, he laughed.

“Forget it. In my view, it’s marketing,” he said. “It’s marketing for companies, it’s marketing for politicians, but it has no scientific basis.”

While discussions continue across Europe, most agree that France has come up with what is currently the best solution. Chick culling in France will come to an end at the end of 2022. Hatcheries will be provided with subsidies to adopt technology that determines sex by day 15. In the case of error, which occurs approximately three per cent of the time, regulars will permit day-one culling. Detection is easier in brown eggs, so because the French prefer brown layers, in-ovo sexing solutions will be cheaper. Dutch poultry economist Van Horne quoted an additional price of €1.20 per bird.

“The French, I think, have found a nice solution and a very pragmatic way to solve the problem,” Van Horne concluded.

Print this page