Cold-weather Ventilation

By Shawn Conley

Features Business & Policy Emerging Trends Equipment Poultry Production Production ProtectionIt’s a matter of timer

Air shouldn’t fall on to heaters, but travel further into the barn before dropping to prevent heaters from running too often. John Menges

Air shouldn’t fall on to heaters, but travel further into the barn before dropping to prevent heaters from running too often. John Menges”Even those who fancy themselves the most progressive will fight against other kinds of progress, for each of us is convinced that our way is the best way.” – Louis L’Amour

This quote by L’Amour applies to all forms of progress, even in our poultry industry. A great example is ventilation, and, specifically at this time of the year, cold-weather ventilation. There have been many significant innovations in cold weather ventilation in the last decade – some you may have heard of but not understood; others you may not have thought worthwhile but they deserve another look.

Timer fans instead of variables for exhaust, sidewall and ceiling inlets, circulation fans, humidity and CO2 sensors, static pressure levels and controller options are just some of the keys to succeeding in cold weather. Heaters are also an important factor, but could easily fill a whole article themselves. For now, it suffices to say that if you are producing a commercial bird today and still using forced-air heating instead of radiant, you aren’t just burning gas, you are burning cash.

Timer Fans and Inlets

If you’ve ever experienced uneven bird distribution, water condensation on walls or wet litter near the walls, the issues stem from variable speed fans and continuous inlet systems.

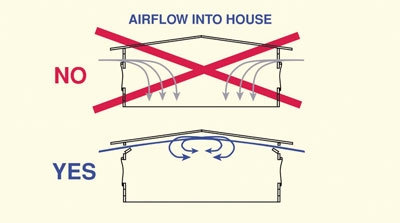

Essentially, when using variable speed exhaust fans, you are trying to ventilate with a constant flow of air. Think of it as a freight train that has to build speed, and you want to stop it as little as possible to make sure it doesn’t lose momentum, but the exact opposite is happening! Your air has no momentum, and falls straight to the floor, chilling your birds and condensing water in your litter. Ideally, the goal is to bring air into the barn at a high velocity along the ceiling, allowing it to preheat and mix with hotter air as it begins to drop.

But, how do we accomplish this?

There are two parts to this: modular inlets and timer fans. Variable speed fans and continuous inlets are a problem, not a solution, in cold weather, and with a continuous inlet system is practically impossible to open a precise amount along its entire length. Looking along the edge of your baffle, it is easy to see how inconsistent the opening is.

Adding modular inlets to the ventilation system allows for precise control of air intake, consolidating the air into a tighter column, giving it the momentum required to shoot over the birds and heaters toward the middle of the barn before descending toward the floor. This is a problem that can be avoided by creating an air column along the ceiling. Imagine how many more heaters are running when cold outside air is hitting the sensors as the air drops just a few feet inside the barn.

The second part is timer fans because you simply cannot create the required static pressure by running air continuously. By running your fans at 100 per cent for 60 seconds out of every 180 to 300 seconds, you enable enough air to be sucked in at high velocity to reach the centre or far side of the barn without reducing the temperature of the barn at bird level.

This strategy keeps the air fresh. The static pressure levels in this system need to approach 0.10 inches H2O, unlike your warm weather levels of about 0.05-0.07. As a rule of thumb, without obstructions, you should get about two feet of air travel for each hundredth unit of pressure.

As well, ceiling inlets offer another level of incoming air control. Not only do they provide precise air volume control, but also they pull air from the attic, which acts as a giant heat exchanger. The air comes into the barn exactly where you want it – in the centre.

Humidity and CO2-based Ventilation

Along with ammonia and carbon monoxide, humidity and carbon dioxide are the main reasons that we have minimum ventilation requirements. Most climate controllers available have the capability to accept sensors for both of these measurements. Ammonia, CO, and CO2 levels seem to follow humidity, so ventilating for it will keep these gases in check.

Everyone is familiar with the effects of high ammonia levels, such as blindness and air sac damage, but high levels of CO are associated with aortic rupture, as well as uniformity and weight gain issues.

Some controllers include programs that will automatically ramp up ventilation as humidity and CO2 increase, while others can be manipulated to run your first-stage fans when levels get too high. By wiring the same fans into two sets of relays, the first set can run your preset fan program and the second can activate the fans whenever humidity and carbon dioxide set points are reached. This is an excellent way to manage ventilation during brooding when little air is needed, and can allow you to keep humidity levels high enough to prevent dehydrating young birds.

Circulation Fans

Stratification of air in poultry barns can cause thousands of BTUs to be wasted. Whether you are using radiant or box heaters, a large amount of heat will immediately rise from the heaters to the ceiling, and not return to floor level.

Fortunately, returning this heat to the birds is a simple process.

You can estimate the number of fans required to de-stratify the air by calculating 10 per cent of the total air volume of the barn and dividing by the CFM of the circulation fan you intend to use. For example: A 250 x 40 foot floor of a barn with a 10-foot ceiling would have a volume of 100,000 cubic feet3 of air. Ten per cent of this is 10,000 CFM. Therefore, with 2500 CFM fans, only four would be necessary. Box fans and basket fans will do the job, whereas tube fans will create more of an “air cannon” effect and not mix the air properly. Ceiling fans can also work well, especially when run in reverse to suck up air and push it out along the ceiling. In open-truss or cathedral-type barns, a fan referred to as a turbulator does a great job of moving air. You can view a video of it on Mike Czarick’s website, www.poultryventilation.com or at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MX9nZSONeBc&feature=player_embedded. In the video, you can clearly see the smoke stays in the peak until the fan is activated, proving the value of circulation fans in moving this heat throughout the barn.

All of these ideas truly are the tip of the iceberg, but hopefully they provide a place to start in your quest to perfect your cold-weather ventilation. I would encourage you to do your own research about the options that are available, but utilizing timer fans, modular inlets, humidity monitoring and circulation fans will make a huge difference.

Shawn Conley is with Weeden Environments in sales and technical service, in Canada amd internationally. He manages projects with many U.S. poultry companies and works frequently with researchers in the industry. Management in pharmaceuticals, a degree in cell and molecular biology and some NCAA and professional basketball preceded his six years working in the poultry equipment and feed-additive industry. Being a former Ontario farm kid, his motivation is to help producers build a strong Canadian poultry industry. He can be reached by e-mail at shawnc@weedenenvironments.com or shawn.d.conley@gmail.com.

Print this page