Fighting Bird Flu

By Carol Moore and Natalie Osborne

Features Health Research Avian influenza – popularly known as bird flu – had the entire world on edge in 2003. There was a surge in the number of people contracting the virus and the hunt for the disease’s origins was global. Biosecurity Poultry ResearchResearchers from the University of Guelph and elsewhere are working towards vaccines for chickens.

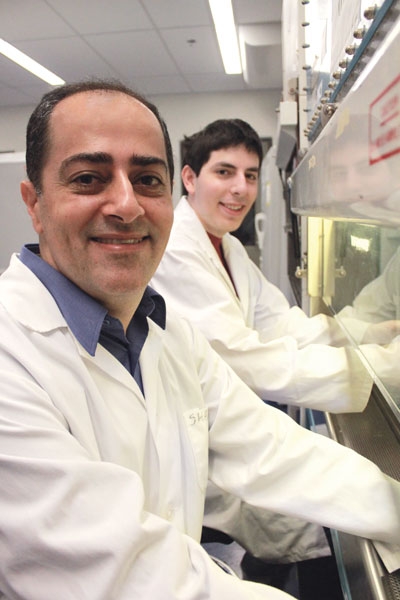

University of Guelph Animal and Poultry Science professor Shayan Sharif (left) – pictured here with Masters student, Michael St. Paul – is leading a team of scientists developing a chicken vaccine that they hope will curb disease transmission between animals before it gets to humans. Photo by Bruce Sargent, SPARK, University of Guelph

University of Guelph Animal and Poultry Science professor Shayan Sharif (left) – pictured here with Masters student, Michael St. Paul – is leading a team of scientists developing a chicken vaccine that they hope will curb disease transmission between animals before it gets to humans. Photo by Bruce Sargent, SPARK, University of Guelph Avian influenza – popularly known as bird flu – had the entire world on edge in 2003. There was a surge in the number of people contracting the virus and the hunt for the disease’s origins was global.

It ultimately fell off the radar screen as the number of reported cases dropped. But the reappearance of avian flu in Hong Kong in November 2010 proves that the threat remains. Even with current surveillance methods, the risk of a pandemic still exists.

Avian flu H5N1 virus does not spread among humans like other similar influenza infections, such as H1N, but it is extremely lethal. Up to half of those infected with the H5N1 strain of avian influenza virus will die.

The Search for a Vaccine

A research team from the University of Guelph and elsewhere is trying to develop vaccines for chickens, to stop disease transmission between animals before it gets to humans.

First, team members need to determine the vaccine’s optimum ingredients.

Team leader Prof. Shayan Sharif, Department of Pathobiology, says the group is looking for avian influenza antigens (viral molecules or molecular fragments) that trigger an immune response. They are using an assortment of laboratory techniques to determine which antigens should be incorporated into the vaccines to generate the most protection against the influenza.

“We want to see if we can contain the viral infection in chickens,” says Sharif. “Once it readily spreads among humans it’s likely that we could see a severe pandemic, because of the high mortality rate.”

Sharif and his team are deciding which antigens to incorporate into the vaccine, based on the level of immune response observed. By looking at the response to specific antigens, the researchers will better understand which parts of the avian influenza virus are involved in generating immunity against the virus. This will enable them to construct the most effective vaccines.

Prototype Vaccine

At this point, the researchers have successfully created a prototype vaccine that is immunogenic – meaning it induces an immune response. However, the presence of immune response does not guarantee protection.

“We are taking this project one step at a time,” says Sharif. “The first step was to see if the vaccine was immunogenic or, in other words, if it could generate immune responses. The second step is to do animal challenge trials to determine efficacy of the vaccine.”

When an animal is infected, it can shed the virus even after the clinical signs of illness have disappeared. Most influenza vaccines are unable to fully prevent this shedding, which can transmit the virus to other animals or even humans. What’s more, birds can shed through both their respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, increasing the chance of disease transmission.

The prototype vaccine is able to reduce the amount of virus in tissue, decreasing virus shedding in infected chickens. Now researchers are working on different formulations that will enhance the ability to limit propagation and shedding of the virus as well as increasing immunogenicity.

“In the case of our prototype vaccine, it looks like we have both immune response and protection,” says Sharif. “The ultimate goal is to reduce clinical signs in birds and transmission of the virus, and we’re hoping to do both.”

Other researchers involved in this project include Dr. Shahriar Behboudi, University College, London, U.K.; Dr. Mansour Haeryfar, University of Western Ontario; Prof. Éva Nagy, and laboratory staff members Dr. Amirul I. Mallick, Hamid Haghighi and Leah Read, University of Guelph.

This research receives support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the Poultry Industry Council, the Canadian Poultry Research Council, the Saskatchewan Chicken Industry Fund and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Print this page