Everybody agrees that there is no good way to depopulate poultry in an emergency but there are times, such as during the outbreak of disease, when mass slaughter or “depopulation” of birds is the only way to protect human health.

So what is the “best” way to depopulate?

The jury’s still out.

Mass depopulation options that are currently available to respond to an

AI outbreak or natural disaster in the United States include cervical

dislocation, the use of carbon dioxide gas (CO2),

which includes whole or partial house gassing, containerized gassing

systems, gassing birds under polyethylene sheeting and other mobile

gassing or electrocution systems, and now firefighting foam.

No one method can cover all circumstances and each method has its pros

and cons. The challenge is to balance the protection of workers and

aggressive disease control with animal welfare issues while finding a

method that is practical, effective and humane.

While animal welfare advocates debate the physiology of the death of

the birds using foam, others continue to raise questions regarding the

practical application of firefighting foam.

The emergency use of firefighting foam was conditionally approved in

the United States in November 2006 for floor-housed poultry but it has

yet to be accepted as a viable option here in Canada.

An Emerging Technology

Bud Malone is an extension poultry specialist at the University of

Delaware. In 2004 he was faced with the challenges of

CO2 depopulation methods during an outbreak of low

pathogenic avian influenza. One of the responders on the disposal team

was also a volunteer firefighter who happened to mention using foam to

fight a fire at a poultry farm, and so the idea was conceived.

A team of University of Delaware researchers began to investigate the

use of firefighting foam as a mass depopulation method in hopes of

addressing challenges that arose during the use of carbon dioxide – challenges such as procuring adequate manpower, training and protecting

the team, disposal of contaminated material and the speed of response

to an emergency situation.

How Foam Works

Firefighting foam was originally used to fight fires as far back as the

late 1800s. The foam is designed to fight forest fires and certain

types of structural fires. The foam concentrate is technically known as

a synthetic detergent hydrocarbon surfactant and it is biodegradable

when mixed with water at the recommended ratios, typically around one

per cent concentration.

The mode of action in fire fighting is the formation of a foam blanket

with a consistency similar to shaving cream, cooling down the fire and

coating the fuel to prevent its contact with oxygen. With poultry, that

same foam blanket covers the flock with a blanket of foam whose bubble

size is small enough to enter the trachea and cause death by hypoxia.

Practical Considerations

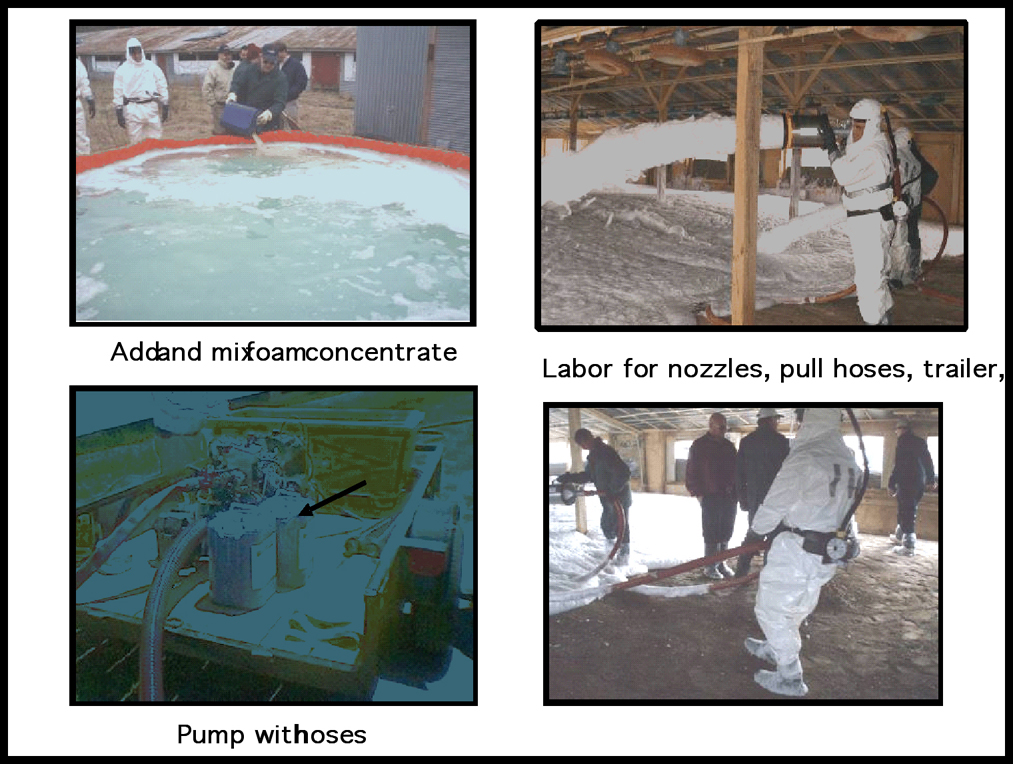

At present there are two technologies available to apply the foam in the appropriate consistency and density.

The aerated nozzle-based system developed in North Carolina mixes water

and foam concentrates in collapsible tanks on the farm. This applicator

is more conducive to use in smaller houses where up to eight

individuals may be required to manoeuvre the hoses and nozzles in the

barn. In a disease control zone this technology would work best for

those houses not actively shedding the virus since it does require more

people coming in contact with the birds.

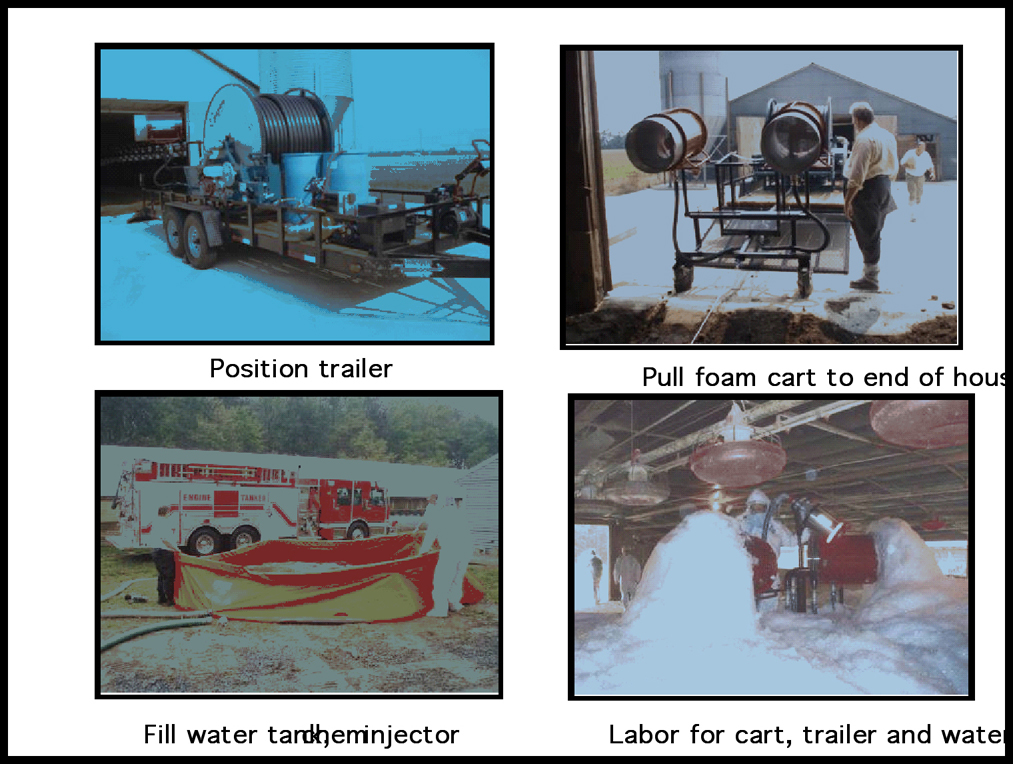

Kifco is an Illinois-based manufacturer and developer of commercial

irrigation equipment that has been working with researchers at the

University of Delaware to develop a high expansion foam generating

system for use in poultry barns called the Avi-FoamGuard. Andrew Baker,

spokesperson for Kifco, explained that the applicator looks like a

large-barrelled searchlight mounted on a three-wheeled trolley.

Baker described how the unit, which costs between $30,000 to $55,000

US, is retracted through the centre of the barn while a generator

delivers a medium-expansion foam with small, dense bubbles. The foam

rolls to the edges of the barn until an overall height is achieved to

cover up the tallest of the birds, which can be up to one metre or more

for large turkeys.

A broiler barn of 40 feet by 600 feet will take 72,000 cubic feet of

foam to fill to a height of three feet and will require 4,250 gallons

of water. The whole procedure for this size of barn would take about an

hour with two people needed to manage the equipment and only one of

those people needs to enter the house.

One of the major incentives to developing foam technology has been to

reduce the human health implications and the complications of working

with gas during zoonotic disease depopulation situations. Once a

responder has suited up with respirators, suits, boots and gloves to

the required level of personal protection and compliance for working

with gas, it’s not so easy to handle either the equipment or the birds.

The labour-intensive procedures that are involved with the four

acceptable methods for carbon dioxide depopulation (whole house,

container, polytent and mobile gassing systems) are avoided with foam.

In addition, the use of foam eliminates human exposure to carbon

dioxide or other gases that may pose safety risks to human health.

When the emergency involves a barn damaged by a tornado or earthquake

and perhaps unsafe to enter, foam may be the only practical option for

mass depopulation.

While firefighting foam is not readily available in large amounts in

Canada, it is commercially available and has a shelf life of up to 25

years, meaning that it can be stockpiled for emergency use as needed.

Carbon dioxide, on the other hand, can be difficult to secure in

adequate quantities in emergency situations.

Water is a potentially limiting factor to the use of foam, both in

terms of supply and quality or hardness. And as for disposal, foam is

compatible with composting of the dead birds.

Animal Welfare Issues

While some consider the use of foam to be humane, others refer to the

process as suffocation and as such find it unacceptable from an animal

welfare point of view. Proponents describe how a gentle wave of foam

quietly fills the house, while opponents claim that the foam just hides

the horrors of the dying birds.

Mass depopulation raises different issues than euthanasia and

unfortunately the issue of animal welfare does get complicated in

emergency situations. According to information on the American

Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) website, “Mass depopulation

refers to methods by which large numbers of animals must be destroyed

quickly and efficiently with as much consideration given to the welfare

of the animals as practicable, but where the circumstances and tasks

facing those doing the depopulation are understood to be extenuating.

Euthanasia involves transitioning an animal to death in a manner that

is as painless and stress-free as possible. The AVMA currently

considers that destruction of poultry using water-based foam is a

method of mass depopulation and not a form of euthanasia. The AVMA

supports additional research to evaluate whether water-based foam can

be accepted as a form of euthanasia.”

Such research is ongoing as the technology develops.

Bud Malone explained that his research team has addressed the concern

that the foam may “drown” the birds. Through pathological examination

of dead birds they determined that no foam actually entered the lungs.

Death is caused by blockage in the trachea: the foam bubbles trigger

the rapid onset of hypoxia.

When carcasses were examined to compare death by foam, which physically

induces hypoxia, and carbon dioxide, which chemically induces hypoxia,

the lesions were consistent: the birds died by similar mechanisms.

Further research using blood analysis for corticosterone levels as an

indicator of stress has shown no difference in the birds’ stress

response between the depopulation methods.

Advocates of the use of carbon dioxide or other inert gases believe

that the gas renders the bird unconscious before death by hypoxia;

therefore, the addition of inert gas to the foam may help to avoid pain

or distress.

Malone’s original intent was to fill the foam bubbles with

CO2 gas. The research team studies, however,

showed that adding the gas did not reduce the time to death for the

birds. The use of foam alone is the safer method of mass depopulation

in terms of human health.

Mohan Raj is a senior research fellow in Food and Animal Science at the

University of Bristol in the U.K. His research is focused on effective

but humane slaughter of animals. Referring to euthanasia, he points to

a legal requirement of stunning methods to induce an immediate loss of

consciousness until death, and he maintains that any method of killing

should be without avoidable pain or distress.

To that end, Raj’s research continues to look into to addition of gas

to the foam. He points out that the foam needs to be robust enough to

feed through the house but the bubbles need to be fragile enough to

deliver the gas. In one trial he filled the foam with nitrogen, which

left the birds dead within 40 seconds, but the birds did experience

convulsions that need further trials to evaluate. Whether such wing

flapping is a sign of conscious suffering is not yet known.

Many questions remain unanswered, but if scientists can develop the

techniques and technology to include inert gases without increasing the

human health risk due to gas exposure it may further reduce some

welfare concerns.

Trial Runs

Foam was used for the first time in large-scale depopulation in West

Virginia in April and July of 2007 in response to the detection of low

pathogenic avian influenza in turkeys at two separate farms. Bud Malone

describes walking into a worst-case scenario: the large, market-ready

birds weighed in at 18 kilograms and required a depth of 1.2 to 1.5

metres of foam.

What did the response teams learn?

“These two foam depopulation events provided a great learning

experience and the opportunity to build on our knowledge base when

using this technology in the future,” said Malone.

He suggested three areas that need to be addressed after these events:

more training of qualified resource people is needed to operate and

maintain the mechanical systems and implement the proper procedures for

foam depopulation, and ample water supply of satisfactory quality and

an adequate supply of the proper type of foam concentrate need to be

sourced and delivered.

In July 2007, firefighting foam technology came to Canada. Ontario, to

be more precise. Dr. Harold Kloeze, co-chair of the Humane Destruction

Committee with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), was there.

As far as Kloeze was concerned, it failed. No one had counted on the

high limestone content of Ontario water that resulted in the foam not

foaming. He suggested that the foam method may be, “great under certain

conditions, but they may not exist here.”

Further research is needed to determine if a particular type of foam

concentrate may work better with hard water or if softening the water

is the answer.

Kloeze points to significant differences between the U.S. and Canadian

poultry industries that led to foam technology being, “probably not as

applicable here as there.”

For example, the infrastructure is not the same. In Delaware,

single-storey barns will house tens of millions of birds on earthen

floors where the use of plastic to seal the barns for

CO2 on such a large scale may be impractical. Here

in Ontario our barns are smaller and designed to keep out our Canadian

winters, which means they are also better constructed to keep in carbon

dioxide for use in the case of emergency depopulation. As well, many of

our barns are multi-storey buildings that are not designed to handle

the huge weight of the water involved in the foam depopulation method.

“Local solutions are needed,” says Kloeze. “Our industries aren’t the

same.” To that end, what he would like to see in the near future is an

inventory of housing types so that appropriate depopulation methods can

be evaluated and prescribed.

There are also practical dispensing problems with the foam which limit

its use at this time: while it pumps in well to open houses it doesn’t

flow around barriers such as cages, creating air pockets and reducing

the effectiveness of the process.

Conclusions?

For the Canadian poultry industry? There are no conclusions yet. The

debate continues. Kloeze says that the CFIA do not have a protocol at

this time for the use of firefighting foam and experts are awaiting the

results of further U.S. research.

In the U.S., “the recent conditional approval of water-based foam by

the USDA and endorsement by AVMA gives the poultry industry another

option for mass depopulation of flocks,” said Malone. “All methods used

for mass depopulation, particularly for zoonotic diseases, must take

into consideration, and balance, poultry welfare and human health; and

must minimize biosecurity risk and logistical challenges.”

At least firefighting foam offers another option for depopulation, and

while no option will ever be entirely palatable everyone seems to agree

that we’re just doing the best we can.

References:

American Veterinary Medical Association, Use of Water-Based Foam for the Depopulation of Poultry (2006).

http://www.avma.org/issues/policy/poultry_depopulation.asp

Malone, B., Benson, E., Alphin, B., Van Wicklen, G., and Pope, C., Methods of Mass Depopulation for Poultry Flocks with Highly

Infectious Disease (2007) Proceedings to Symposium on

Emerging Diseases, Queretaro, Mexico.

Print this page