Euthanasia: The Human Toll

By Karen Dallimore

Features Farmer Health/Safety Health Business/Policy CanadaFailure to make the right decision doesn’t impact just the animal in question

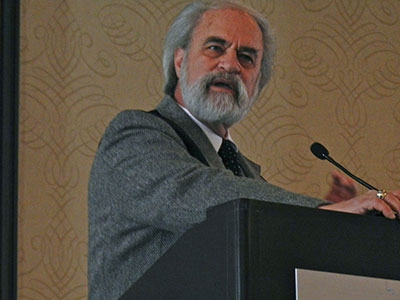

Dr. Jan Shearer, DVM, says that veterinarians suffer a huge emotional toll from the decisions and circumstances around euthanasia. Karen Dallimore

Dr. Jan Shearer, DVM, says that veterinarians suffer a huge emotional toll from the decisions and circumstances around euthanasia. Karen DallimoreThe room went silent for a moment as Jan Shearer fought to keep his composure, unable to speak. “I struggle sometimes to give this presentation,” the veterinarian from Iowa State University told a gathering of Farm and Food Care (FFC) delegates at a meeting in Guelph earlier this spring.

His presentation was about what he called the “caring and killing paradox” – the emotional toll of being called on to perform euthanasia, but not always for humane or medical reasons.

Veterinarians struggle with euthanasia for the sake of convenience. For example, a dog is no longer wanted because the owner has redecorated the house and the dog doesn’t match the colour scheme anymore. “Do I send this person out the door and possibly send this animal to a terrible death?” he asked. But on the other end of the spectrum, what about when an owner wants to continue treating an animal regardless of the animal’s quality of life, only because they can’t let go?

Dealing with the destruction of healthy animals creates a moral stress for the veterinarian, whose life is devoted to maintaining the well-being of animals. This can create a condition not dissimilar to post-traumatic stress disorder, called perpetration-induced traumatic stress. “It’s a very real issue,” said Shearer, “one day a healer; the next day an executioner.”

One study in the United Kingdom has revealed that veterinarians are three times more likely to commit suicide than the general population. Shelter workers, laboratory technicians and even young people in 4-H clubs are exposed to the caring and killing paradox, marked by depression, grief and other destructive behaviours that can include alcohol and drug abuse. “It takes a toll,” said Shearer, “a real toll.”

Shearer described the difference between human and animal cognition by quoting Bernard Rollin, a philosophy professor at Colorado State University: “In the animal mind – there is only ‘quality of life.’ It’s painful or it’s not, hungry or not, thirsty or not.”

Humans, on the other hand, will endure short-term negative experiences for the purpose of achieving long-term goals. “To be the animal’s advocate we have to keep these things in perspective,” said Shearer.

The euthanasia procedure can be stressful for a caregiver when the animals are suffering as well. “In a perfect world, we would preserve all life and relieve all suffering by medical or other means,” said Shearer. “Reality is, there are many conditions in animals, whether caused by injury or disease, that result in excruciating pain and/or horrible suffering that cannot be relieved by any other means than euthanasia.”

Either way, as a veterinarian, Shearer looks for a so-called “good death,” where life is ended without pain or distress to the animal. “This requires a technique that induces immediate loss of consciousness followed by cardiac and respiratory arrest which results in a loss of brain function and death.”

“It’s complicated,” he said, adding that the emotional aspects are harder to deal with than the actual procedure; “the decision is not always black and white.” No one likes or wants to do it, and all are afraid of the possibility of acting too soon.

Research is improving euthanasia procedures and the Iowa State University website provides extensive information on euthanasia, including such aspects as equipment maintenance.

“Killing can be kind,” said Shearer, again quoting Bernard Rollin. “Better a week too early than a day too late.”

Print this page