To Trim or Not to Trim?

By André Dumont

Features Health Turkeys Business/Policy Canada Poultry Research ResearchUniversity of Saskatchewan research provides new insight into turkey toe trimming

Hank Classen is a professor at the Department of Animal and Poultry Science of the University of Saskatchewan. His research shows toe trimming may not be necessary on heavy toms. courtesy of André Dumont

Hank Classen is a professor at the Department of Animal and Poultry Science of the University of Saskatchewan. His research shows toe trimming may not be necessary on heavy toms. courtesy of André DumontToe trimming in turkey production is a well-established practice, but is it really necessary? Last November, professor Henry L. (Hank) Classen presented his research team’s findings at the AQINAC poultry conference in Drummondville, Que. Assisted by graduate student Jocelyn Fournier; Classen investigates behaviour and performance of treated and non-treated turkeys.

Classen pointed out that existing research on toe trimming was rather outdated. “The genetics of these birds has dramatically changed since the 1970s and 1980s. The technology used to trim toes has also changed.”

Because of this significant evolution in turkey production, several important questions remained unanswered. With toes being important for balance and mobility, how do shorter toes affect birds with considerably more breast muscle than 30 years ago? Now that Nova-Tech Engineering’s Microwave Claw Processor has replaced surgical scissors or cauterizing hot blades, do birds suffer less from the toe trimming procedure?

Classen’s research was based on the hypothesis that toe trimming can decrease carcass scratching without negative effects on bird welfare. The effect of toe trimming was measured on production criteria (growth, feed efficiency and carcass damage) and bird welfare criteria (toe length and variability, toe healing, gait score/stance and behaviour).

Classen said there was a need to assess animal welfare other than by measuring carcass damage from scratching and condemnation. Treating toes using microwaves may reduce bacterial infection, but could the trimming be too severe?

The experiment was conducted on groups of 32 Hybrid Converter hens per pen, from zero to 15 weeks of age, and groups of 17 Hybrid Converter toms per pen, from zero to 20 weeks of age. Two treatments were compared – no toe trimming and toe trimming – using the Microwave Claw Processor. The birds were grown to ages older than what is common practice in Canada but comparable to world standards.

|

| Chart courtesy of University of Saskatchewan

|

Results

There was no significant difference in body weight between treated and non-treated hens after 15 weeks. However, at 20 weeks, untreated toms did weigh around half a kilogram more than treated ones.

A closer look at body weight gain over time revealed that both treated and untreated toms had comparable body weight gain for the first 70 days, but things changed as the birds got bigger. “This lends itself to the idea that the treated birds were somewhat reluctant to go to the feeder,” Classen said.

For both hens and toms, treated birds had a reduced feed intake from zero to seven days. According to Classen, this suggests that birds are affected by the treatment.

Treated toms also had a reduced feed intake at 126 to 140 days, confirming the hypothesis that there is a reluctance to feed and grow to genetic potential.

However, in agreement with previous experiments, the overall feed to gain ratio seemed not to be affected by toe trimming. Mortality was higher with treated birds, but in the context of the experiments, the difference was not statistically significant.

Of much greater concern was the number of treated toms that by the age of three weeks had a rotated tibia, a condition that can be found in birds that suffer physical damage to their legs because they are exposed to slippery surfaces. In this case, researchers suspect the cause may be the absence of claws on straw bedding.

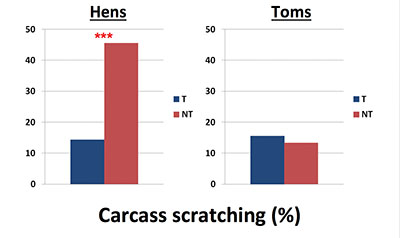

The experiment’s most interesting finding relates to scratching. With hens, a very significant reduction in carcass scratching was observed among treated birds. Among the toms, there was very little carcass scratching in both treated and non-treated groups. “At 20 weeks of age, those toms weigh more than 20 kilograms. They are big birds. It’s possibly their size alone that reduces the potential for scratching,” Classen said.

As for toe length, it turns out treated birds have toes that are about eight per cent shorter. Toe regrowth is very variable. A close look at toes shows that by 14 days, most of the healing is done. In three out of four samples, bacterial colonies were found in treated toes, suggesting the microwave treatment is probably not a complete barrier to bacteria entry. But overall, the treatment was found to be consistent and effective.

Researchers were surprised to find that when encouraged to walk, both hens and toms showed good mobility despite their large size. However, during the first week, treated birds did have a reduced activity level. “These effects were basically gone by the end of a week,” Classen said. “The effect was slightly less in hens than in toms, but the bottom line is that these birds probably experience some type of discomfort or pain.”

Because the toe is innervated (it has nerves that can send pain signals), there is undoubtedly pain caused when severing it with microwaves, Classen explained. “There is no question that these birds probably need a little additional care after the treatment.”

Conclusions

Although the research was conducted on a small flock in experimental infrastructures, conclusions may be relevant to commercial turkey breeders.

In the case of hens, toe trimming is recommended despite welfare issues early in life. Classen says that this is counterbalanced by reduced scratching.

Researchers recommend against toe trimming toms, especially those grown to heavier sizes. There was indication of pain after treatment, reduced growth at later ages and an increase in rotated tibia. Most importantly, untreated toms did not suffer more carcass scratches. “For toms observed in this experiment, we have negative things that add up, and nothing positive to counterbalance.”

This research was sponsored by the Canadian Poultry Research Council, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and Lilydale.

Print this page