Hypereye: A game changer

By Melanie Epp

Features Production Poultry Production Poultry Research Specialty ResearchCanadian technology that identifies bird gender in-ovo could be the answer to one very big issue in egg production.

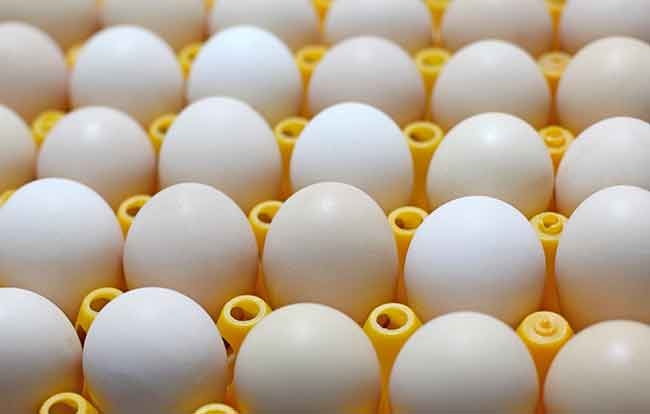

The “Hypereye” will reduce waste by identifying which eggs are male and infertile, allowing only fertile female eggs to be incubated. Fotolia.

The “Hypereye” will reduce waste by identifying which eggs are male and infertile, allowing only fertile female eggs to be incubated. Fotolia.Every day nearly 62,000 cockerels are culled in Canada. That’s 22.5 million birds each year. While the number sounds shocking, it is the harsh and unavoidable reality of Canada’s egg industry. In the developed world, that number reaches over a billion chicks. The birds that commercial egg farms purchase are bred specifically for egg, not meat, production, which means that while the females are highly coveted, male chicks have absolutely no value.

This is not only a serious animal welfare issue, but also an issue of waste. But technology developed by the Egg Research Development Foundation (ERDF) could change all that.

Hatcheries in Canada run a tough business. According to Tim Nelson, Chief Executive Officer of the Livestock Research Innovation Corporation (LRIC), when you take into consideration their losses, they run at 50 per cent efficiency. For one, some 10–15 per cent of all eggs are infertile, and hatcheries are forced to dispose of them as waste. Of those that do hatch, cockerels make up 50 per cent. The chick must then be identified, culled and disposed of by the hatchery. On top of the waste and animal welfare issues this raises, the hatchery must foot the bill for their incubation, as well as the labour and energy associated with raising them.

In 2007, the industry started working towards a solution. Egg Farmers of Ontario (EFO) has been funding research for a new technology, tentatively called “Hypereye,” that uses hyperspectral imaging to identify infertility and gender in day-of-lay eggs. If successful, Hypereye could be a game changer for Canada’s egg industry.

Hypereye uses spectroscopy, which is technology that allows hatchery personnel to identify eggs that are infertile. More importantly, though, it allows them to determine gender of the day of lay. Since day-of-lay eggs are essentially the same as regular table eggs, early identification could mean a new source of eggs. The potential, said Nelson, is huge.

Dr. Michael Ngadi, a food and bioprocess engineer at McGill University, is the head researcher on the project. In a recent interview, he explained how the Canadian technology differs from similar technology being developed around the world. A team in Germany, he said, is also using spectroscopy, although their approach is much different.

“We combine spectro-image data, so that’s why we call it the hyperspectral imaging,” explained Ngadi. “It’s a combination of broad spectral image signatures that we get from the egg. Then we put that through a fairly complex mathematical analysis where we are using some deep learning techniques to identify or relate those spectral and image data to the specific attributes that we are looking at – in this case, whether it is fertile or not and whether it is male or female.”

Dr. Ngadi said that they have chosen not to go into the infrared range for a number of reasons, mostly because he doesn’t see it as commercially feasible to operate at that wavelength. “Also because you will not be able to get an image at that wavelength,” he added.

Hypereye is almost ready for market. In fact, Nelson said that it could be ready as early as mid-2017. At present, the bench-scale model operates at an accuracy of 99 per cent. On a commercial scale, Hypereye must be able to process 30,000–50,000 eggs per hour. Currently, it’s nowhere near that speed, said Nelson, although he’s confident that speed won’t be an issue. “It’s just a case of ramping up the software,” he said. “Speed is important, but accuracy is more important. Right now we’re not worried about speed.”

The Poultry Industry Council in Ontario first provided funding for the project in 2007. Preliminary results were so successful that EFO decided to invest in further research, which is now being conducted through the McGill University in Montreal.

Currently, ERDF is looking for a qualified commercial partner who will assist taking the technology into production, and then market and service it around the world. ERDF believes that there will be considerable interest in the technology, especially since the approach they take keeps the eggs intact. Other systems, explained Nelson, involve invasive DNA testing. Not only is DNA testing time consuming, but it also requires putting a hole in the egg. There is greater risk of contaminating the eggs with bacteria and transmitting disease between eggs, and partially incubated male eggs and incubated infertile eggs have to be destroyed.

Since Hypereye will enable hatcheries to determine gender and infertility on the day of lay, eggs need not be wasted. Theoretically, said Nelson, the egg industry could take a large number of hens out of production. This is unlikely, though, especially as new egg markets are opening up. One such market, said Nelson, is the pharmaceutical industry. In recent years, EFO committed $1 million to Relidep, an antidepressant drug that requires thousands of fertile eggs each day. Nelson said the food processing market will take them as well.

Harry Pelissero, EFO’s general manager, says Canadian egg producers need not worry about production loss. “The non-female eggs could be used either for other uses such as table or breaker markets, vaccine egg production or for production of anti-depressants,” he said. “Given the ever-increasing use of eggs as a source of protein, existing egg farmers should not be worried about any reduction of egg production as a result of the implementation of this process.”

While the announcement is an exciting one for the industry, it could be a while before Hypereye is available commercially for large-scale operations.

“There are a whole lot of variables in the industry that we need to account for when we are actually putting this thing out there,” said Nelson. “Age of flock may make a difference, what the flock’s being fed may make a difference, and genetics of the flock may make a difference. So there’s a whole lot of things we have to take into account.”

The long and the short of it, though, is that the technology is there. “And because this is day-one and because it’s non-intrusive, it’s really important technology,” said Nelson.

Pelissero agreed. “We are getting closer to building a prototype, testing and will be in a position begin to take orders within the next two years,” he concluded.

Print this page