With food safety among the top concerns of Canadian consumers these

days, industry and governments alike are looking for better ways to

ensure it – including irradiation of animal carcasses and expanding its

use to more food products.

Food irradiation is an effective tool for removing pathogens and it has the science to back it up, but consumer acceptance is the stumbling block

With food safety among the top concerns of Canadian consumers these days, industry and governments alike are looking for better ways to ensure it – including irradiation of animal carcasses and expanding its use to more food products. “I think it’s time an informed public looks at all the information and makes a decision about irradiation,” says Rick Holley, “in light of the fact that contaminated animal carcasses are an important factor in causing food borne illness outbreaks.” Holley is an industry consultant, professor of microbial ecology of food spoilage at the University of Manitoba, and member of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency academic advisory panel.

|

| Not Always Accepted. Treating raw meat and poultry with irradiation is an effective tool for virtually eliminating bacteria such as E.coli, and Campylobactor but Canadian consumers are wary. It’s used in the U.S., but irradiated meat must be clearly labelled as such.

|

Irradiation of carcasses, he believes, should be used along with many other practices to ensure safe meat is delivered to consumers. “I liken the technique to pasteurization in the way that it was established a long time ago, and although pasteurization did cause some changes to the food, but the benefits were quickly seen to far outweigh any detractions,” Holley says. “Irradiation is a major solution to Campylobacter contamination in poultry, and we can make great strides in food safety if we use it to treat poultry carcasses.” Holley points to studies in the U.S. where 18 per cent of whole chickens and 45 per cent of turkeys were Salmonella positive, and a whopping 95 per cent of chickens were Campylobacter positive. In the EU, he says Salmonella contamination of broiler flocks has been found to be up to 66 per cent.

The U.S. Center for Disease Control echoes these views. “Treating raw meat and poultry with irradiation at the slaughter plant could eliminate bacteria commonly found raw meat and raw poultry, such as E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Campylobacter,” states the agency on its website. The Center also says irradiating prepared ready-to-eat meats like hot dogs and deli meats could eliminate the risk of Listeria from such foods and, in addition irradiation could eliminate bacteria like Shigella and Salmonella from fresh produce.

The safety of irradiated foods has also been endorsed by the World Health Organization, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Health, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food products approved for irradiation in the U.S. began with wheat flour in 1963, pork, fruit, vegetables and spices in 1986, and poultry products in 1992. Also currently approved for irradiation in the U.S. are prawns and ground beef. Ron Eustice, executive director of the Minnesota Beef Council and an irradiation proponent and educational researcher, says the volume of irradiated foods marketed in the U.S. annually is estimated to be 175 million pounds of spices and botanicals, 15 million pounds of meat, and 25 to 30 million pounds of produce. Other countries that have begun to irradiate food include France, the Netherlands, Portugal, Israel, Thailand, Russia, China and South Africa.

Expansion of the use of irradiation to carcasses and other food products in the U.S., says Eustice, “will depend on several factors including future outbreaks, use and effectiveness of other interventions and litigation.” The greatest opportunity for use of irradiation lies in the area of imported produce, he says. “This market is growing dramatically because of USDA agreements with several nations.”

To date in Canada, products that have been approved for irradiation treatment are potatoes, onions, wheat, flour, whole wheat flour, whole and ground spices, and dehydrated seasoning preparations. The process for approval of irradiation of specific new foods in this country begins when a petitioner provides Health Canada with a submission, which must contain sufficient data, generated inside or outside Canada, for scientific and technical review to demonstrate the efficacy of the irradiation treatment and the safety of the resulting food products. “When the safety evaluation is complete, if the submitted data is considered satisfactory, then Health Canada can consider beginning the regulatory work necessary to legally enable the use of irradiation on the requested food,” says Health Canada media relations officer Philippe Laroche.

Chicken-and-egg situation

The Canadian Poultry and Egg Processor’s Council (CPEPC) is also supportive of the technology. “We believe irradiation is a good tool with good science behind it, and we’d like to see its use approved for poultry carcasses,” says CPEPC president and CEO Robin Horel. “However, before we would make an application to Health Canada for that, consumer attitudes would need to change.”

|

|

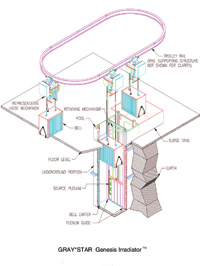

| Irradiation kills organisms that cause foodborne illness. As in the heat pasteurization of milk, the irradiation process greatly reduces but does not eliminate all bacteria. Irradiated poultry, for example, still requires refrigeration, but would be safe longer than untreated poultry. The energy source is either gamma rays (produced by a radioactive element such as cobalt) or electrons (produced by electricity). Electron radiation breaks up the bacteria’s DNA, making it impossible for the bacteria to reproduce or continue living. Iowa State University Photo courtesy of GRAY*STAR, Inc., Michigan |

Moving forward with poultry carcass and poultry product irradiation, in Horel’s opinion, hinges on promotion and education from a source that Canadians strongly trust as a first step. “If consumers don’t see irradiation as a plus, as a selling feature, then none of my members would use the technique and want it on the packaging,” says Horel. “Health Canada seems to be ok with the science, but we want them to come forward to say so to the consumer.”

When asked about whether Health Canada would undertake public education and/or promotion of irradiation of poultry carcasses or poultry food products, Laroche says the department does not promote the use of any particular product or technology. “However, Health Canada does try to educate the public about food safety in general as well as specific technologies that may be used to help ensure food safety,” he says. “For example, Health Canada maintains a document on its website entitled ‘Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Food Irradiation.’”

Laroche notes that Health Canada is the ‘regulator,’’ and as such, its role with respect to new technologies like irradiation is only to review the scientific information to determine safety and effectiveness. However, he adds “Health Canada is looking at the public understanding and perceptions of food irradiation…[and] continues to review all available information from Canadian and international sources published in research journals on irradiation to inform policy development.”

Outbreak prompted irradiation support

However, in the ‘Independent Report prepared for the Government of Canada’ after the Listeria outbreak in summer 2008, one of the recommendations reads “Health Canada should review its approval processes and fast track, where appropriate, new food additives and technologies that have the potential to contribute to food safety giving particular attention to those that have been scientifically validated in other jurisdictions.” Furthermore, as the Toronto Star’s new services reported in August 2008, “Dr. Jeff Farber, director of Health Canada’s Bureau of Microbial Hazards, said the government is considering approving the irradiation of meats by early 2009.” When questioned about this statement, Laroche says “It is impossible to say whether the availability or the use of food irradiation would have prevented the Listeria outbreak. In theory, irradiation can reduce the amount of bacteria present in treated foods at a given time. However, depending on the stage of production at which point a food is irradiated, and the handling of the food following irradiation treatment, they can become re-contaminated. Irradiation does not, and should not, replace good manufacturing practices.” That is something no one disagrees with. “Irradiation must be positioned as an additional step and not a replacement for existing technologies,” says Eustice.

It should also be noted that prions, the protein particles associated with BSE, are not inactivated by irradiation, except at extremely high doses, and irradiation does nothing to eliminate viruses. Holley also lists the stability of plastic packaging to irradiation and oxidation of fats as concerns. He adds that at the recent CPEPC Symposium in Saskatoon in June, Dr. Scott Russell from the University of Georgia suggested it would require 120 irradiation facilities across the U.S. to irradiate all the poultry in the U.S., and his alternative approach is to treat poultry carcasses with chemicals like chlorine.

Education is key

Like Horel, Eustice sees education of the public as critical. “The level of support for irradiation increases dramatically with education,” he says. His research (with universities such as the University of Wisconsin-Stout and University of California at Davis) shows that after people have received information on irradiation, “it is realistic to expect 85 to over 90 per cent approval for the technology.” “Once people are informed, they accept irradiation,” agrees Holley. “The price to pay is minimal, the technology is well established, so why not?”

Holley has recently received funding from the Canadian Beef Cattle Research Council to begin studying irradiation of beef carcasses in conjunction with a researcher at Health Canada. “We will look at survival of non-O157:H7 toxigenic E. coli in a study that will last several years,” he says. “We will subject beef cuts inoculated with six strains of E. coli to irradiation, and follow them through normal processing to patties.”

If we want to have an immediate effect on foodborne illness in this country, Holley concludes, “we should be irradiating poultry carcasses. With its use, human cases of foodborne illness caused by Campylobacter (the largest contributor to illness from contaminated food) would likely be reduced by 25 per cent or more.” Holley believes Health Canada should reconsider its role and try to coordinate public education efforts. However, he accepts that “If the government of the day does not want to move forward, Health Canada will make no such move. Unfortunately, it may take another food- borne illness crisis or two to see action.”

Print this page