Leading the Pack on Biosecurity

By David Schmidt

Features Business & Policy Farm BusinessB.C. ready to launch its new mandatory producer program

Three years after an avian influenza outbreak decimated the Fraser

Valley poultry sector, the British Columbia poultry industry is finally

starting to roll out its new poultry biosecurity program.

Three years after an avian influenza outbreak decimated the Fraser Valley poultry sector, the British Columbia poultry industry is finally starting to roll out its new poultry biosecurity program. The program will be mandatory for B.C.’s 318 chicken, 130 table egg, 69 turkey and 57 hatching egg licensed producers and act as a pilot for the rest of the country.

Three years after an avian influenza outbreak decimated the Fraser Valley poultry sector, the British Columbia poultry industry is finally starting to roll out its new poultry biosecurity program. The program will be mandatory for B.C.’s 318 chicken, 130 table egg, 69 turkey and 57 hatching egg licensed producers and act as a pilot for the rest of the country.

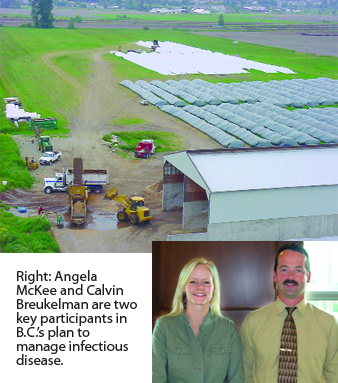

“I started chairing the B.C. Poultry Association biosecurity subcommittee in fall, 2004, and this has been ongoing since then,” says Abbotsford hatching egg producer Calvin Breukelman, adding “the whole project took longer than I hoped for.”

In early 2005, the sector received commitments or up to 3.25 million dollars in federal and provincial funding to develop and implement a biosecurity program and emergency response plan. The funding was intended to cover developmental and initial delivery and audit costs and provide assistance for producers to implement the new biosecurity requirements.

The British Columbia Poultry Association decided to follow the Environmental Farm Plan (EFP) model so they hired Niels Holbek and Ron Bertrand, co-coordinators of the B.C. EFP program, to also co-ordinate the new biosecurity program.

“Our task was to help get this program put together and off the ground,” Bertrand explains. “We were to develop the workbook and reference materials, help with administration of the money and review producer applications for funding.”

Bertrand and Holbek worked with the B.C.PA, the four marketing boards, allied trades, the provincial and federal departments of agriculture and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to develop the standards.

“The program has two basic goals,” explains delivery co-coordinator Garth Bean. “One is to keep an infectious disease from getting into a production unit and the other is to keep it from getting out of a production unit if it’s there.”

For program purposes, each production unit has been identified as a “Controlled Access Zone” (CAZ). It almost always includes only one species, although it may often include more than one barn. A CAZ is not the same as a farm, which could include two or more CAZs if, for example, the various barns are on two sides of a public roadway or a farm has separate production units for layers and turkeys or layers and chicken.

After almost a year of discussion and debate, the program has been pared down to 18 mandatory standards in four areas. They are (abbreviated):

Farm Access

• There must be a secure barrier at each access point to the CAZ. The barrier can be as simple as a chain, although gates are preferred. While secondary access points must be locked at all times, the primary access point need only be lockable. The primary access point should also be deep enough into the property to allow vehicles to get completely off a public road.

• Each access point must have approved biosecurity signage.

• Primary accesses must have hard surfaces (e.g., pavement) or hard-packed gravel without any potholes.

• Primary accesses must have an approved cleaning and decontamination site with pressurized water for both vehicles and personnel.

• The CAZ must be clean and free of organic debris, e.g., manure, which can be transferred onto footwear, tires or vehicle undercarriages.

Barn Access

• Barns must be locked when unoccupied.

• All barn entrances must have approved restricted access signs.

• All poultry barns must have an anteroom at each primary entrance. The anteroom must provide a distinct separation between the “outside” and “inside” areas. It must include a disinfectant hand-cleaning station and footbath and must allow for a change of boots and outerwear. A free-range farm anteroom must be at least a covered area with a footbath.

• Barn entrances and anterooms must be clean and free of debris.

Flock Health Management

• There must be health records for each flock, which include daily mortality counts, feed intake and egg production records, veterinary and diagnostic reports and any response to an unusual mortality rise. Any addition or removal birds to or from a flock must also be recorded.

• Poultry mortalities and cull eggs must be handled and disposed of in an approved manner, such as on-farm incineration or composting. If mortalities are taken off-farm, they must be moved in disinfected, sealed containers.

Farm Management

• Each farm must have an effective pest control program.

• Each farm must have standard operating protocols to prevent contamination of feed and water sources.

• All poultry-related equipment and materials entering or leaving the CAZ must be clean and decontaminated.

• All farms must have a manure management strategy that documents how the manure was used and/or who transported it off-farm.

• All producers and farm employees must receive regular on-farm biosecurity training.

• Each farm must have Standard Operating Procedures for on-farm biosecurity. These must cover such topics as self-quarantine procedures, farm access, access maintenance, cleaning and decontamination procedures, pest control, manure management and mortality disposal.

• Each unit must maintain a visitor and activity log book that details all actions taken and all visitors to the premises. Visitors do not include regular farm employees and people travelling directly to and from a farm residence.

Planning workbook

To help producers meet the standards, a planning workbook similar to that used in the EFP program has been developed. The workbook begins with a sample poultry farm site layout that helps producers determine their own CAZ(s). It then goes through a series of 75 questions which help producers determine where the standards are being met, where action is required, and where the minimums could be “enhanced.”

“Enhancements” are a key component. For example, in the case of farm access, having a farm residence outside the CAZ is an “enhancement” rather than a requirement. Similarly, shower-in, shower-out facilities in an anteroom are an enhancement rather than a requirement.

Not all questions apply to every producer. For example, some are specific to egg handling, while others apply only to free-range operations. The workbook also includes an extensive reference guide that provides background and complete details for each standard and offers examples of basic and enhanced measures.

Planning advisors

As delivery co-coordinator, Bean, who also co-ordinates the EFP program for the B.C. poultry industry, is co-coordinating a group of nine planning advisors who will help producers walk through the checklist and develop a farm-specific biosecurity program that meets the required standards. Each of the advisors is already a certified EFP advisor specially trained in the requirements of the biosecurity program.

Producers are not required to use a planning advisor, but Bean can think of no reason not to.

“It’s no cost to them and I think the farmers will find it of value,” he says, pointing out use of a planning advisor at least partially fulfils the requirement for biosecurity training. He also hopes producers use the opportunity to complete both the biosecurity and the EFP program, since many of the requirements in the two programs overlap.

“Less than half of B.C. poultry producers have completed an EFP program,” he notes.

There is also considerable overlap between the biosecurity program and the poultry industry’s on-farm food safety programs.

“Chicken growers have very limited work to become compliant because most of their requirements are already in the Safe, Safer, Safest program,” Bean notes.

“The process is bringing clarity to both the biosecurity and food safety programs,” Bertrand adds.

FUNDING

Once a producer has gone through the checklist, he or she can apply for funding to implement measures required to meet the standards. The program will provide one-third funding for approved measures to a maximum of $5,000/CAZ. Although the application must be approved before a producer can proceed with the measure, the producer must complete the measure and pass a compliance audit before being reimbursed.

Although producers can apply for funding for both basic and enhanced measures, only basic measures will be funded until Oct 16th.

“In mid-October, we will review the applications and if it looks like all the money has not been used for basic measures, we will look at funding enhanced measures,” Bertrand said, adding it is unlikely basic measures will use up all the available funding.

Bean believes this is another reason to combine the biosecurity and EFP programs, noting measures which qualify as EFP Beneficial Management Practices can receive funding under that program. The EFP program not only has a higher per farm cap, it usually offers a higher funding percentage.

The program is intended to be mandatory for registered producers and is therefore being incorporated in the B.C. Broiler Hatching Egg, Chicken, Egg and Turkey board orders. The six board inspectors (three chicken and one each for egg, hatching egg and turkey) will then conduct compliance audits on each farm.

AUDITS

Although the inspectors did mock audits of an egg farm and a turkey farm in January, BCBHEC inspector Angela McKee expects the official audits will begin in June.

“Initially, we are going to rely on Garth and his group to tell us who’s ready for an audit,” she said.

While each of the boards has it own inspector(s)/auditors, McKee says they intend to work together. “We realize there are farms with multiple commodities and our aim is not to audit the farm more than once.”

While the biosecurity audits will be separate this year, the hope is to do a single audit of both the biosecurity and food safety programs next year.

“We are keeping the programs separate but as an auditor, I won’t ask the same question two or three times.

Biosecurity will just become an addendum to food safety,” McKee says.

Eventually the two will become one. As the B.C. representative on the national avian biosecurity advisory committee, McKee is meeting regularly with the CFIA to develop an integrated national system.

“We’re reviewing what’s in the national food safety programs and how the biosecurity program can be incorporated in them,” she notes.

Breukelman hopes that will eventually happen, saying “logistically it makes the most sense.”

In the meantime he believes most producers will not have much difficulty meeting the standards since “most of these protocols are just routine and most producers who are in the food safety program already have a lot of this in place. The biggest issue will be in determining traffic flow. How do you as a producer come onto your own farm, how do your vaccination and catching crews come in and out and so on.

“The most onerous requirement will be the paperwork. Farmers hate having too much paperwork.”

Breukelman also provided concrete examples of how the protocols translate into on-farm practices and what producers could use the funding for, using his own farm as an example.

“I want to put in an automatic gate opener which will be a lot easier for me as a hatching egg producer, I need to put flow drains in my anteroom and better sheathing on the walls to make it easier to clean and I need to bring pressurized water from my barn over to the decontamination site.”n

Print this page