Modern Broilers

By Chance Bryant technical manager North America west region Cobb-Vantress Inc.

Features Broilers Health Poultry Production ProductionThe old management rules don’t apply

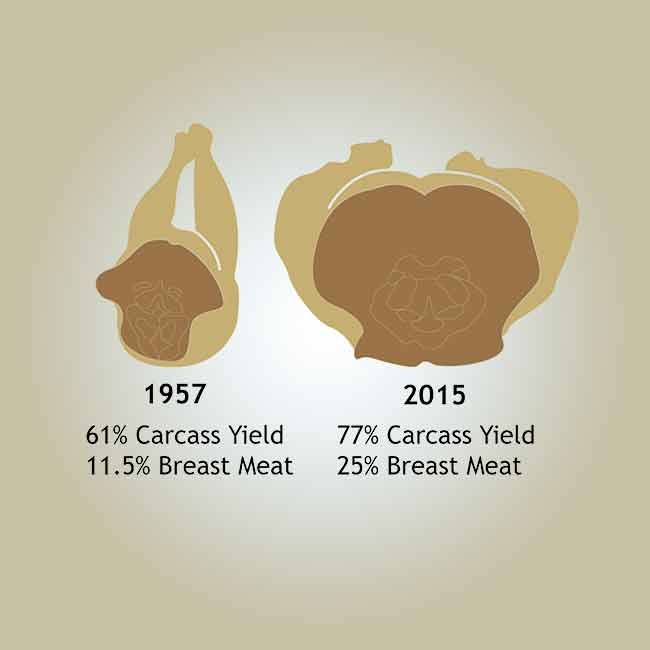

The broiler of today is considerably bigger and more efficient than decades ago. Yet, many of the standard management practices we use today originated in the 1980s. Those same rules simply don’t apply today.

The broiler of today is considerably bigger and more efficient than decades ago. Yet, many of the standard management practices we use today originated in the 1980s. Those same rules simply don’t apply today.

Every year, we strive to bring innovative solutions to every facet of the poultry industry, including genetics. As birds continue to evolve, so too must our management practices.

In 2016, pullets, hens and broilers are vastly different genetically than they were 30 years ago. Today’s birds want to grow faster. They are more feed efficient. And these traits are passed down through breeding stock.

When comparing benchmarks such as average daily gains (ADG), weight at 42 days of age and meat on carcass, broilers in 2010 were roughly 50 per cent larger than they were in 1980.

Yet many of the standard management practices we use today originated in the 1980s. Those same rules simply don’t apply today.

The following tips on how to manage 21st century birds are important for everyone throughout the complete production line – from grandparent (GP) to processing and everything in between.

New Housing Parameters

As we have seen progression in poultry genetics, housing has also needed to change to accommodate a more efficient and larger bird.

In older facilities, everything was manual. They were smaller in capacity, more labour intensive, less efficient and the birds weren’t kept as comfortable. Today, houses are controlled exclusively with computers – managing the ventilation, temperature, feed lines, water and lights – allowing birds to realize their full genetic potential.

And as demand increased, farms grew and houses often contained more birds or total pounds. Manual systems could not have kept up with today’s ventilation systems, which include bigger, more efficient fans, complex air inlet systems and controllers with multiple settings to account for changes in temperature throughout the year.

Ultimately, it comes down to creating the best environment for birds. The better the birds’ environment, the better the end product will be. Therefore, making investments in housing updates or additions now will pay for itself in the long run.

New Management

While broilers have nearly doubled in size over the last 30 years, breeding stock weight standards have changed very little. The only way to achieve those weights is through extremely precise management techniques.

All birds want to be broilers by nature and want to eat and grow. It is our job to restrict the pullet/hen weight to a similar weight as 20 to 30 years ago so they will still produce eggs. With genetic improvements weighted heavily toward broiler production, it’s harder and harder to keep the pullet/hen from trying to grow too quickly.

More Feeder Space

In pullets/hens/broilers, uniformity is key to efficient production and having healthy flocks. Yet, because today’s birds convert feed more efficiently and grow faster, they need proper feeding space more than ever before.

Giving pullets and hens adequate feeder space – ideally, having available 11.5 – 15 cm per bird (4.5 – 5.5 in.) on chain system and 12 to 14 birds per pan on pan system – ensures that birds eat the same amount at the same time. Managing the intake, spacing and timing reduces competition for food, resulting in better uniformity and feed efficiency.

Because broilers are growing more quickly, getting feed management correct from the start is more important than ever. In 1967, brooding (the first seven days) equated to only 11 per cent of the bird’s total 63-day lifespan that it took to achieve 4.4 pounds. Today, brooding is 21 per cent of the bird’s total grow-out of 33 days to achieve 4.4 pounds. With a shorter lifespan, there simply isn’t time to correct mistakes made in that first week.

Water Needs Have Increased

Today’s 35-day old broiler is more like a 50-day old broiler 30 years ago. We’ve already examined several ways this impacts the birds’ needs, and water is no different. Birds need more water because they are developing more quickly. Broilers drink at a ratio of 2 to 1 in relation to water to feed consumption. Thus, if water is restricted, the birds will not eat the needed feed to grow properly. When the lights first come on, it is an extremely high demand time for water. Monitor house meters during the first two hours after the lights come on to ensure all houses are getting

adequate volume.

For pullets and hens, the need for water spikes right after feeding. Water systems should be able to provide approximately 11 to 12 gallons per 1,000 birds for the three hours following feeding. However, antiquated systems cannot keep up with this volume and only provide birds with about five to six gallons per 1,000 birds. That’s only half of their actual need. For newer houses or retrofitted water systems, plumbing needs to be able to handle the peak volume during feeding, not just the overall flow throughout the day.

The results of insufficient water are dire in pullets/hens:

- Increased possibilities of choking birds.

- Difficulty achieving the proper weight.

- Extended cleanup time of feed intake.

- Excessive slat eggs, because birds stay at the feeder/water longer and don’t go to the nest in time.

- Reduced peak egg productions.

Complex Ventilation Systems

We cannot ventilate houses the way we did years ago because of the growth of the bird. Modern ventilation systems have numerous components to provide the optimal environment. They monitor the levels of ammonia, carbon monoxide (CO2), and dust inside the house. They control the temperature as well as relative humidity (RH), which keep the birds comfortable and the litter dry.

To create the best environment for birds, it’s crucial to first understand basic principles of ventilation.

- Static Pressure (SP) – For every .01 of SP air is thrown ~61 cm (2 ft.)

- Relative Humidity (RH) – For every 11.1 C (20 F) the temperature increases, RH decreases by 50 per cent.

These are the three “must-haves” of minimum ventilation:

- Must have correct SP for your building

- Must have correct air inlet door opening

- Must then determine proper run time to control humidity in house

Getting any one of these components wrong could lead to unsuccessful ventilation. Always use the company-provided ventilation rate charts of your particular system, but consider factors such as outside temperature and RH to adjust as needed.

Stir fans are also a key piece in maintaining an even temperature throughout the house to break up stratification of hot and cooler air. This also keeps litter dry by controlling the moisture level throughout the house.

Greater Heat Stress

We have controls throughout the chicken house to monitor the temperature. However, that doesn’t take into consideration the temperature of the birds.

The most important factor is the bird’s core body temperature, especially during feeding time when birds are in such close proximity and prone to excitement.

For pullets and hens, managing temperature at feed time is crucial for proper feed intake, optimal performance and peak production. Be aware that birds are eating in areas of the house that typically aren’t monitored by the controller temperature sensors and are congregated tightly together during feeding, producing lots of BTU’s. Overheating at this time can cause excessive mortality, increased floor/slat eggs and poor performance. Ventilation/air flow should be increased during this time to manage bird temperature.

In broilers, we should pay special attention to bird temperature once they become fully feathered. Feathers act like an insulation and make it more difficult for birds to release excess heat. One misconception is that just because you grow small birds, over-heating isn’t a problem. The truth is that because you can place more small birds in any house, they actually produce more heat than larger birds that are less densely placed at the same respective age.

Over and over again, we see examples of ways that pullets, hens and broilers have dramatically evolved over the past 30 years. And with that we must constantly adapt and fine-tune our management practices – as well as the housing facilities – to meet the needs of these new, larger and more efficient birds. By providing birds with the optimal environment, we can better realize their genetic potential while maximizing performance and production.

Print this page