Optimizing Genetic Gain

By Ben J. Wood Hendrix Genetics Ltd. Kitchener Ont.

Features Business & Policy TradeReconciling reproduction, yield, and body weight

Reconciling reproduction, yield, and body weight in a nucleus turkey breeding program

|

| PROFITABILITY OF PRODUCTION Ben Wood (above) explains that by using a selection index based on factors impacting profitability, the nucleus turkey breeder aims to breed a product that optimizes the profitability of production at each level of the chain. |

|

Balanced breeding is the catchphrase used by all of the primary breeding companies, but what this means or how it is developed is less understood. Here, I will describe the development of the economic values used by Hybrid Turkeys (a division of Hendrix Genetics Ltd.) to assist in setting its breeding goals.

The breeding goal should take into account all the economic impacts on production and also some factors that do not, yet these non-economic factors can also have an impact in the market and on breeding goal.

The commercial turkey

industry has a well-defined structure with implicit input costs and

returns and for this reason it is well suited to economic modelling.

The behaviour of the system can be described in terms of mathematical

equations that define the relationships between production variables.

The input variables must be reasonable (and validated) to give the

results power but given this proviso the importance of each trait in

the breeding objective can then be defined.

A model that accurately describes integrated commercial turkey

production should by definition apportion the appropriate selection

weight to each trait. The following model estimates margins using

commercial production and processing costs together with processing

plant production returns.

|

|

|

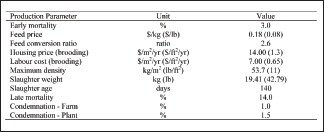

| TABLE 1. MANAGEMENT AND COMMERCIAL PRODUCTION BASE PARAMETERS |

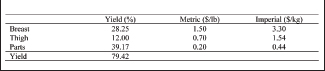

TABLE 2. CARCASS YIELD (% OF LIVE WEIGHT) AND CARCASS COMPONENT VALUE |

Breast meat yield, feed conversion and body weight have significant impacts on the margin; similarly, the reproductive traits (egg production, fertility and hatchability) also have an effect on profitability through their impact on commercial poult cost. By using a selection index based on factors impacting profitability, the nucleus turkey breeder aims to breed a product that optimizes the profitability of production at each level of the chain but that ultimately optimizes profitability of the whole integrated company.

PRODUCTION MODEL

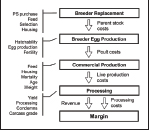

Turkey production was evaluated as a whole system with each component contributing to profitability through the supply chain (Figure 1). Commercial poult cost is a function of the cost of obtaining parent stock hens and rearing to capitalization, level of parent stock tom selection, costs through lay, number of eggs produced, fertility and hatchability.

|

| FIGURE 1. SUPPLY CHAIN WITH SIGNIFICANT INPUTS AT EACH LEVEL (MODIFIED FROM WOOD AND BUDDIGER 2007) |

The cost in conditioning until selection includes feed and housing (taking into account maximum growing density), labour costs and mortality along with parent stock poult costs. The cost of a selected breeder candidate is increased proportionally to the number of parent stock selected minus the revenue generated from the commercial processing of non-selected breeder parents. Post-selection (assumed 20 weeks) the birds still need to be kept until the start of production. Costs through this period are principally housing and feed costs taking into account once again the density the birds are kept under and the expected mortality at which time the cost of a capitalized breeder can be calculated.

Through the laying period the cost of feed, housing and labour need to be calculated against the time in lay and laying density. Additional cost is involved in investment in parent stock and rearing costs before obtaining a return in commercial poult production. Once these costs are calculated, the poult cost is then a function of these costs spread over the number of eggs produced corrected for fertility and hatchability.

Model equations for commercial production and processing are scaled to a common unit of cost and profit per live weight delivered to the processing plant. Poult cost previously calculated is adjusted to account for birds that do contribute to returns but are lost as mortalities in production. Brooding and commercial housing cost are calculated using the maximum density in each, slaughter age and brooding and slaughter weights.

Maximum housing densities were included with housing described in terms of cost/area/year to better reflect the change in capacity with different slaughter weights. Feed cost is calculated using the expected feed conversion, slaughter weight and feed price. An adjustment is made for birds taken from the commercial house but lost due to condemnation, consequently adding to the cost of production without a resulting increase in revenue. The total cost of production per live weight delivered can then be calculated as the sum of the cost of feed, housing, adjusted poult cost plus the added correction for birds lost to condemnation divided by the slaughter weight.

The cost in processing a carcass was calculated as the sum of the fixed overhead cost per bird and a variable cost related to the speed and efficiency of the line. The total cost of processing is then divided by the slaughter weight. Revenue generated from the processed bird is a function of the yield and the value of the meat yielded from each carcass. The total return per weight processed is then the sum of these values. The margin for production is then calculated as the value of the processed meat subtracting the cost of production and processing.

MODEL PARAMETERS

Commercial base values for production are shown in Table 1 with these figures validated against industry values (Agri Stats Inc, 2007). Base carcass composition and the value of each component of the carcass are shown in Table 2. The carcass parts value was simplified to only include breast, leg and parts with latter comprised of a composite of the lower value components of the carcass with wing, rack and giblets. Individual values for these elements add little to a margin analysis given the relatively small value compared to the breast and thigh.

RESULTS

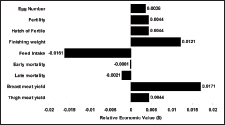

The economic values (EV) for a one unit change in a trait can be calculated and in the strict sense these values should be used to calculate the index and goal in a breeding program. An easier method to visualize the importance of each trait is to use the relative economic values, which take into the amount of genetic variation present and give an indication of the change that could be achieved.

The relative economic values are shown in Figure 2. From the figure, the importance of bodyweight, breast meat yield and feed consumption (or conversion) has on margin, and consequently, the relative economic value is clearly visible. They all have similar and relatively large economic values compared to the other traits. The reproductive traits had a significant but relatively smaller economic value compared with feed, weight and yield.

RESULTS OF INDEX SELECTION

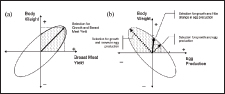

The overall result of selection for a combination of body weight, yield and egg production can be described in terms of the genetic relationship or correlation between the traits. The relationship between body weight-yield and body weight-egg production are positive and negative, respectively. The relationship and the result of selection based on a combination of selection based on a balanced objective are shown in Figure 3.

The figure displays two dimensionally the possible outcomes of selection when there is either a positive (a) or negative (b) correlation between two traits. When there is a positive correlation, as for example between body weight and breast meat yield, selection for either trait will result in a strong selection for the other trait with the greater response depending on the economic value of each trait.

In contrast, negatively correlated traits selection in one trait can lead to a decrease in the other such as increasing body weight at the expense of egg production. The middle ground, selecting for decreased body weight gain whilst maintaining or increasing egg production is the heart of balanced breeding. Using the example of two traits it is easy to visualize but when we move above two or three traits the number of dimensions cannot be visualized and we rely in the economic values calculated to place the appropriate weight on each trait to optimize the genetic gain.

To obtain the correct balance across all the traits in the breeding objective, appropriate weights must be apportioned to each when making a selection decision. This is further complicated when we consider that the economic values previously calculated are at the parent stock level for reproductive and commercial level for production traits. Reproductive traits expressed in the female line are often the result of a two-way cross and the commercial product is a further cross such that it can be the combination of three or four pure lines.

Transfer of the economic values must be such that the sum of the selection weights in the pure lines (or pedigree birds) closely matches that calculated for the whole integrated balanced breeding objective. Matching the selection weight of each line is required to produce the balanced parent stock and commercial product.

|

| FIGURE 2. RELATIVE ECONOMIC VALUES FOR TOM PRODUCTION IN AN INTEGRATED TURKEY COMPANY |

|

| FIGURE 3. SELECTION BETWEEN TWO TRAITS AS VISUALISED IN TWO-DIMENSIONAL GRAPH WITH TRAITS WITH POSITIVE (A) AND NEGATIVE (B) CORRELATION (MODIFIED FROM WOOD 2007) |

CONCLUSION

Feed intake, body weight and breast meat yield have a major impact on the profitability of integrated turkey production and consequently have relatively large economic values on which to base index selection. Of lesser value but still significant are the reproductive traits expressed in the breeder flock and mortality expressed in the commercial flock.

The economic values show the clear trend in the industry towards growing turkeys to increasingly heavier weights for further processing. The significant value of reproductive traits, particularly egg number, shows that a turkey selection goal must include some level of selection pressure on reproduction. With four-way cross-breeding, the challenge is to translate the economic value at the commercial and parent stock levels into separate breeding objectives for pure lines whose genetics constitute one half of the breeding stock or one quarter of the commercial bird.

REFERENCES

Agri Stats Inc. 2007. Monthly Turkey Reports, Fort Wayne, IN.

Wood, B.J. 2007. Genetics – where can we take it? International Poultry Practice. 21:17-19.

Wood, B.J. and N. Buddiger. 2007. Calculation of economic values for turkey breeding using a production model. Association of Animal Breeding and Genetics. 17:45-48.

Print this page