Perinatal broiler feeding research project

By Lisa McLean

Features Nutrition and Feed Gut healthProtein common in milk may help early gut growth in broilers.

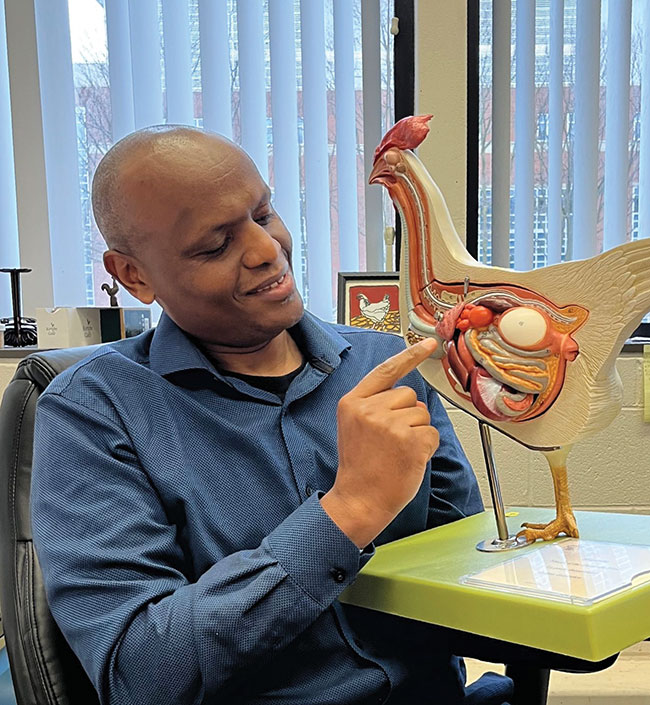

Dr. Elijah Kiarie holds the McIntosh Family Professorship in Poultry Nutrition at the University of Guelph. PHOTO CREDIT: Dr. Elijah Kiarie

Dr. Elijah Kiarie holds the McIntosh Family Professorship in Poultry Nutrition at the University of Guelph. PHOTO CREDIT: Dr. Elijah Kiarie The first 10 days of life are crucial for a broiler chick’s fragile digestive system, and exposure to harmful pathogens can lead to poor growth and health issues. As the industry phases out preventative antibiotics, researchers are looking for new ways to make a bird’s digestive system stronger, faster – using a protein that is commonly found in milk.

Dr. Elijah Kiarie of the University of Guelph is working with epidermal growth factor (EGF), a protein that helps with healing. It’s activated when it binds to EGF receptors that are found along the length of the small intestine in poultry.

“One of the many ways to make a chicken’s digestive system more robust without relying on antibiotics is to develop the gut quickly,” Kiarie says. “We want young chicks to eat and absorb nutrients as quickly as possible in those first 10 days, so they are stronger and more developed.”

Starting with the egg

As part of Kiarie’s work, he has been testing the most effective way and time to deliver EGF to enhance a bird’s intestinal tract. First, he had to confirm when EGF receptors appear in a chicken’s small intestine so he could take advantage of accessing them as early as possible.

Kiarie administered EGF in ovo, directly into the egg, and investigated the presence of EGF receptors at various stages from days 17 to 21. “What we found is that the EGF receptors only appear on day 21 — when chicks hatch. Once we understood that, we realized it would be more effective to apply EGF directly to feed,” Kiarie says.

The challenge with chickens

The small intestine is lined with villi, tiny hair-like projections that help absorb nutrients. Rapid growth of the small intestine in the first 10 days of a chick’s life is an indication of better gut health. Kiarie says by day seven, a chicken’s small intestine typically comprises about seven per cent of its body weight.

“The challenge with chickens is that they must be able to consume enough nutrients to form their gut in the first 10 days after hatching, and it takes almost three days after hatching for them to access their feed,” says Kiarie. “Our goal is for chickens to develop a more robust small intestine as quickly as possible so they can digest more food.”

EGF in feed

Kiarie’s team fed groups of chickens diets containing four different concentrations of EGF. They compared their results with a control group — one that used antibiotics and one that did not. All chickens were fed their designated diets and brought to market weight.

“If you improve villi, chickens can express more enzymes, and if they express more enzymes, they should be able to digest more food,” Kiarie says. “The birds receiving EGF had healthier, heavier small intestines – but we saw no other advantages.”

In an unexpected twist, all birds – regardless of diet and the use of antibiotics – consumed the same amount of feed, from day zero to market weight. Kiarie notes that while the birds fed EGF had better intestinal health, all birds in all groups were physically identical. “We went back to the drawing board, to focus on the first 10 days,” Kiarie says. “And we wanted to represent farm conditions.”

This research is funded by the Canadian Poultry Research Council as part of the Poultry Science Cluster which is supported by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada as part of the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. Additional funding is provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Print this page