Poultry Barn Meteorology

By Shawn Conley

Features Bird Management Production Environment Poultry Research ProtectionManaging air quality through humidity control

Shawn Conley writes that when it comes to minimum ventilation, monitoring humidity can be the ultimate tool to manage air quality. Maintaining humidity levels of 50-70 per cent can create ideal gas and particulate concentrations in the barn.

Shawn Conley writes that when it comes to minimum ventilation, monitoring humidity can be the ultimate tool to manage air quality. Maintaining humidity levels of 50-70 per cent can create ideal gas and particulate concentrations in the barn. The old saying “It’s not the heat; it’s the humidity” can be tweaked to apply to a lot of problems in poultry barns: It’s not the dust, the ammonia, the carbon dioxide or the carbon monoxide; it’s the humidity.

Over-ventilating can result in dry, drafty conditions with an unnecessarily high heating cost, while under-ventilating can cause excessive litter and air moisture, and negatively affect bird performance. When it comes to minimum ventilation, monitoring humidity can be the ultimate tool to manage air quality. Maintaining humidity levels of 50-70 per cent can create ideal gas and particulate concentrations in the barn.

One gas that is important to address is carbon monoxide. Although carbon monoxide is generally not lethal to poultry until it reaches levels of 3,000 parts per million (ppm), it can cause measurable distress at 600 ppm, and has been shown to cause ascites around 70 ppm in poultry. It is actually more of a problem for humans than for birds. In reality, heater maintenance will affect the concentration of the gas more than ventilation for two reasons: first, increasing ventilation brings in more cold air, which requires the heater to run more, and second, oxygen levels aren’t reduced enough to allow toxicity to become an issue. Since carbon monoxide is linked to oxygen, it is vital to mention that ventilating to ensure adequate oxygen is not necessary. Air is 21 per cent oxygen, and birds require only six per cent to survive. To provide enough for 20,000 day-old birds, only 16 cubic feet per minute (cfm) of ventilation is required, and normal ventilation rates are over 1,500.

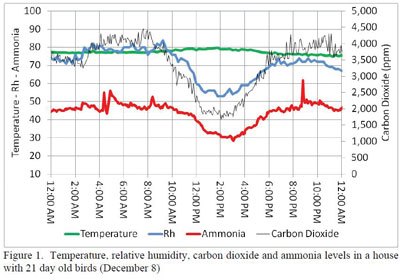

For humidity control, we need to look at how the gases that follow humidity will be at acceptable levels as long as we maintain appropriate humidity levels. The first of two gases that can dramatically affect bird performance is carbon dioxide: a gas that has essentially no effect on performance up to about 6-8,000 ppm. However, at levels exceeding 8,000, performance starts to decline marginally, while above 10,000 ppm, weights can be reduced by over 10 per cent. The target for carbon dioxide based on these numbers should be a maximum of 5,000 ppm. As seen in Figure 1, if humidity levels are maintained at under 70 per cent, levels above this number should never occur, and therefore, humidity control will result in carbon dioxide control.

It is easy to see in Figure 1 that not only does carbon dioxide follow humidity, but ammonia does as well. I don’t need to rehash all the issues that can result from high ammonia levels, but keratoconjunctivitis and air sac issues are a couple that come to mind. Lesions on the eyes due to high ammonia levels quickly cause blindness, and destruction of the cilia lining the respiratory system make it nearly impossible for birds to expunge particulates and bacteria from air sacs. In inoculated birds, Newcastle disease has been shown to infect 100 per cent more birds at 50 ppm of ammonia than at 0 ppm1. The threshold for live weights also seems to be 50 ppm, with close to eight per cent lower than at 25 ppm, whereas feed conversion rates increase by four per cent and mortality is nearly four times that at 25 ppm. There is a theory that because ammonia increased more quickly (4 ppm / min) in relative terms than carbon dioxide and temperature (0.7 F / min), and because oxygen barely decreased in 20 minutes with no fan activity, in power failure situations it is actually ammonia that causes catastrophic mortality.

Ammonia, by far, is the biggest concern, but it is not a practical method to manage ventilation. Ammonia monitoring equipment is expensive and not consistently reliable, so humidity is looked upon as the management tool.

Figure 1: Plot of temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide and ammonia. Mike Czarick, 2012.

Humidity Sensors

Humidity sensors to attach to a barn controller are relatively inexpensive for the benefits they provide, and allow for accurate tracking of humidity data. If it is established that humidity is too high, ventilation levels can be tweaked higher until a balance is achieved. Using gas to increase heat production and warm incoming air might be a necessary evil to get below 70 per cent humidity. The decision must be weighed against bird performance. An essential piece of information to understand is that increasing temperature by 20 F doubles the water holding capacity of the air as it enters the barn, so boosting the target temperature can more effectively reduce humidity than increasing air exchange, and lessens the chance of chilling or drafting.

Keep in mind, however, that humidity’s affect on litter moisture is a cumulative one. Taking advantage of higher daytime temperatures and lower outside humidity by reducing ventilation in the nighttime hours and increasing it during the day can save a lot of money on gas.

Figure 2: Graph of carbon monoxide versus bird age for 20,000 broilers. Brian Fairchild, 2012.

DUST

But there is another side to this story, namely particulates, or in other words, dust.

There are a few reasons a barn can have dust problems, and there are some facilities where the only solution is to use dust clearing technologies like sprinklers, for example, conventional and aviary layer barns, light restricted breeder replacement barns and heavy activity turkey finishers. But in most commercial meat production barns, the majority of dust control can be accomplished through proper ventilation management, and by this I mean humidity management. Not only does dust carry bacteria, but also it can irritate the membranes of the system and increases transmissibility of disease.

High dust levels are also generally an indicator that ventilation levels are too high, and in turn, too much heat is being generated, consuming gas. Taking into consideration all the previous data provided about the other factors in air quality – carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, oxygen and ammonia – if we pull back ventilation enough to elevate humidity above 50 per cent, we should be in good shape. As we do this, we must remember that levels above 65-70 per cent can drastically hurt bird performance, so it is very important not to overcompensate for dust, and consider alternative dust control measures if it is not practical or possible to get levels up.

As with all poultry-related topics, it is difficult to adequately explain all of the ins and outs of ventilating based on humidity, but it is worth the time to do some further research and develop an understanding of what moisture does to a barn.

Consultation with an expert can go a long way. Making use of monitoring equipment will give you incredible insight into what is actually occurring in your barn, and is an invaluable tool. And don’t forget, when it comes to minimum ventilation, it’s not the gases and the dust, it’s the humidity!

1 Miles et al., 2004.

Shawn Conley is with Weeden Environments in sales and technical service, internationally and in Canada. He manages projects with many U.S. poultry companies and works frequently with researchers in the industry. Management in pharmaceuticals, a degree in cell and molecular biology and some NCAA and professional basketball preceded his six years working in the poultry equipment and feed-additive industry. Being a former Ontario farm kid, his motivation is to help producers build a strong Canadian poultry industry. He can be reached by e-mail at shawnc@weedenenvironments.com or shawn.d.conley@gmail.com.

Print this page