ABBOTSFORD, B.C. — There was never a time, Calvin Breukelman says, even

in the darkest moments, when he ever imagined his dream of remaining in

the poultry industry was dead.

ABBOTSFORD, B.C. — There was never a time, Calvin Breukelman says, even in the darkest moments, when he ever imagined his dream of remaining in the poultry industry was dead.

ABBOTSFORD, B.C. — There was never a time, Calvin Breukelman says, even in the darkest moments, when he ever imagined his dream of remaining in the poultry industry was dead.

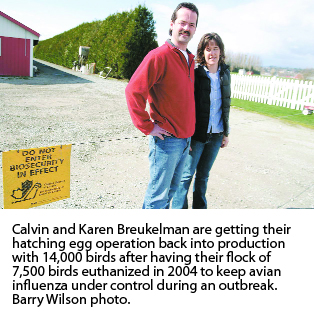

And there were many dark moments for the 38-year-old broiler hatching egg producer and poultry farm manager as avian influenza ravaged his farm and neighbourhood in 2004.

There was the Sunday morning, March 28, after almost two months of evidence that the flu was around, and his neighbourhood was labelled high risk, when he walked into his barn and noticed that his flock seemed different.

By that night, 20 birds in his flock of 7,500 were dead. By the next morning, 150 were dead and many others were listless.

“It is your worst nightmare. I was afraid to go into the barn for fear of what I’d find.”

March 30, when trucks arrived to gas his flock was a dark moment. Almost as dark was when he went into the barn that morning and saw a flock, lively and loud just a day before, now sick and dying.

“It was obvious the flock was deathly sick and there was just a feeling of helplessness,” he said. “I cared for them. They were living creatures. It was awful to see and to hear the silence.”

And when media arrived, when inspectors in biohazard suits were on hand and when the family felt the eyes of the neighbours were on them, there were many dark moments.

“It was a very emotional time,” said Calvin’s wife, Karen. “You felt your privacy was being invaded. You felt everyone was looking at you. You began to feel you had a disease yourself.”

To make the isolation worse, she was not allowed contact with members of her family also in the Fraser Valley poultry business. They could meet only on neutral territory at her mother’s house, not on their respective farms.

“It was very stressful, a lousy time,” Karen said.

But Calvin said he never totally despaired. As president of the British Columbia Broiler Hatching Egg Producers’ Association, he turned his attention to helping his neighbours remain optimistic that they would survive the crisis and to helping the Canadian Food Inspection Agency deal with what became a massive cull of 70 million birds.

“I never ever thought this was the end,” he said. “I knew there would be tough stretches but I knew this was not something that would break us.”

The tough stretches included 14 months out of production and an estimated loss of $100,000.

The Breukelmans are just now getting back to full production with 14,000 birds in their hatching egg operation.

And there are many lessons learned.

He is a leading advocate of strict biosecurity practices within the industry and of vigilance against disease.

There are clothes changes between visits to different barns, regular washings and strict controls on who can enter the barns.

It has increased costs and management hours “but the alternative is losing public confidence in the industry. We have seen the results of that.”

Breukelman said changes must be made in the Health of Animals Act to ensure that farmers who are ordered to have animals destroyed because of reportable diseases receive adequate compensation.

“There are gaps in the present system that have to be fixed and we will be pressing the government to deal with that.”

It could also help having agriculture minister Chuck Strahl living in the neighbouring riding that also felt the effects of the avian flu crisis.

Breukelman said the 2004 episode has made him more sensitive to the growing reports of the spread of bird flu through Asia, Africa and into Europe and warnings that it could resurface here. There are scare reports of a possible mutation of the strain into a human form that could cause a pandemic.

He is frustrated by what often seems like public and official overreaction, a failure to distinguish between more lethal and more benign strains of bird flu.

“It’s not that the industry is turning a blind eye and saying there is no risk,” said Breukelman. “But we have to assess real risk and not overreact.”

He says biosecurity precautions practised in the industry are light years ahead of what existed when he first got into the poultry business in 1989.

“We are doing what has to be done.”

Despite all that has happened, Breukelman said he would make the same choice again to get into the poultry business.

“We both love the business,” he said. “Hatching eggs has been good to us. I’d have no hesitation in getting into the industry again, even knowing the risks that I now know.”

This article was originally published in The Western Producer, March 30, 2006. It has been reprinted with permission.

Print this page