Pest Supplement: Current trends

By Treena Hein

Features Barn Management ProductionPopulation and control strategy updates for mites, flies and more.

In Ontario, there are reports of high populations of rats infesting poultry farms over the past year. PHOTO CREDIT: Poultry Industry Council

In Ontario, there are reports of high populations of rats infesting poultry farms over the past year. PHOTO CREDIT: Poultry Industry CouncilIt’s an approach that’s time-honoured and still holds significant value in pest control: a multi-pronged strategy is a very effective way to manage serious pests like mites, flies and more in the barn. Are there new products and strategies, however, to add to the tool kit, and what threats are of most concern right now in Canada? We contacted several experts to get their views.

First, let’s look the severity and risk level for mites in Canada. Bill Vaughn notes that while there’s no indication that Poultry Red Mites (PRM) and Northern Fowl Mites (NFM) are on the rise, they do remain a sporadic threat. “When farms have the infestation, it is very difficult to control,” says the global director of poultry products marketing at MSD Animal Health (the name for Merck Animal Health outside of U.S. and Canada). PRM, he adds, are also vectors for disease. “Dr. Jenny Nicholds, formerly a practitioner in Canada and now at the University of Georgia (clinical associate professor of avian medicine in the College of Veterinary Medicine), has recently presented a paper proving this,” he says.

This paper, presented recently at the 2018 Proceedings of the American Association of Avian Pathologists, reported on a situation of increased mortality on a Saskatchewan broiler breeder farm. Nicholds, who is still a poultry extension veterinarian at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S), performed necropsies on two flocks. Treatment for a bacterial infection with antibiotics was met with relapse. There was also an apparent increase in the burden of existing PRM. Both the increased hen mortality and mite population had followed the prohibition of carbamates, notes Nicholds, a class of insecticide previously used on this farm for mite control as part of an integrated pest management program.

Nicholds provided E. coli isolates from mites, sick birds, healthy birds and the environment to Dr. Joe Rubin in the department of veterinary microbiology at U of S, and he determined the isolates from sick birds and mites were closely related. Nicholds concluded a final diagnosis of E. coli septicemia, vectored by, and secondary to, parasitism by PRM.

Nicholds notes that PRM were first identified in Saskatchewan in 2013. “They only come out at night, so depending on type of facility, you won’t notice them until there is a big population,” she notes. “In situations where an unfamiliar creepy crawler is observed, the first thing to do is identify the creatures you have. In the case of mites, they could be grain mites or other species that are not poultry pests.”

PRM spends most of its life cycle in the environment, while NFM spends its entire lifecycle on the bird. This impacts the best approach to control, Nicholds notes. Simply put, you have to get the drug to the bug. “For NFM, you can apply the correct product to the birds and/or have them dust bathe in it, depending on product label indications,” she says. “For PRM, it’s going to be crack and crevice treatment.”

Until recently, many mite application options for poultry barns have been quite labour intensive. Additionally, Nicholds notes that between resistance problems and bans on certain classes of treatment, options are also becoming increasingly limited. However, new options are now here. Nicholds says new research has provided adequate information to allow the CgFARAD (Canadian global Food Animal Residue Avoidance Database) to provide withdrawal recommendations for the off-label use of an avermectin product in poultry (Ivermectin).

Administration of this product through drinking water is much easier than spray application and/or dust bathing. Use of these products, however, is still associated with a meat and egg withdrawal time, making it an impractical option for commercial layer flocks.

Another alternative is a fluralaner product (Exzolt), which is licenced in 40 countries for treatment of PRM and has been used in Canada under an Emergency Drug Release. Nicholds says in Europe, it has a 14-day meat withdrawal and zero-day egg withdrawal. She adds that it was used “with great success” on the breeder operation struggling with PRM that was the focus of the study mentioned above, and according to ongoing monitoring efforts using AviVet mite traps and software, the operation remains free of PRM today.

Increasing the heat in the building between flocks is also a way to reduce populations of PRM, says Nicholds, but at the same time, we must remember that some buildings can’t achieve a very high temperature. Specialized pest control companies can bring sources of supplemental heat. Nicholds says the goal is generally 140°F for 30 minutes, but if you can’t achieve that, go as high as you reasonably can for as long as you can. Caution should obviously be practiced, recognizing that not all equipment can withstand sustained high temperatures.

Biosecurity is another big piece of the mite-control puzzle, adds Nicholds. Producers should avoid moving equipment and birds between farms or barns, and mice and rats must be kept away. In Ontario, Al Dam, poultry specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, says he’s heard about high populations of rats infesting poultry farms over the past year. As far back as 2017, fast-growing populations of rats were also reported by CBC in southern Ontario and warm winters were listed as a cause.

Mites, house flies and more

Like mites, house flies can also carry diseases (as well as parasites like mites) and can potentially travel between barns and even farms. Indeed, they have been found to possibly carry 100 organisms that include human and chicken pathogens, and can be a contributing factor in the spread of these microorganisms, notes Simon Lachance, professor of veterinary entomology and pest management in organic systems at the University of Guelph, Ridgetown Campus. These can include, he says, Salmonella and E. coli.

For control of red mites, house flies, darkling beetles and other pests in poultry barns, Lachance notes that it’s important to reduce moisture in manure as much as possible. “Everything [related to water] needs to be examined,” he says. “Water leaks or condensation problems should be checked for and fixed, feeders must be kept at appropriate heights, and then there’s proper ventilation, and so on.”

Lachance and his colleagues have studied the strategy of adding various substances to manure to reduce house fly populations.

“We tried boric, citric and acetic acid, lime, diatomaceous earth and found that boric acid worked quite well, but there is no commercial product on the market for this.”

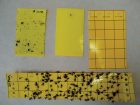

For flies, insecticide sprays can be used on poultry barn walls, granular bait trays and sticky tape can be hung as well. “There are fungal biopesticides that have been shown in studies to work, and while they take a while longer to kill flies, they are another tool that should be used,” Lachance notes.

“They affect flies with another ‘mode of action’ and using several modes of action is important in not only control but in prevention of resistance development in pests. There are various chemistry ‘groups’ in conventional pesticides and then there are biopesticides that employ fungi and other things.

“Resistance can, however, develop even in bioproducts. Sticky tape should be used in conjunction with sprays and will catch any resistant flies. The sticky roll tape that stretches horizontally works the best.”

Biological methods for houseflies

Summarized from ‘House Fly Control in Poultry Barns ’:.

“Parasitic wasps are very small, do not sting people and usually go unnoticed. There are several species of wasps used to control flies. They are purchased as a mixture determined by barn conditions and geographic location. Using several species of wasps provides better control as they have different habitats, temperature tolerances and searching behaviors for seeking out fly pupae.

The Hister Beetle is also a predator of house flies. Larval and adult stages feed on house fly eggs and larvae. The beetles can survive in both wet and dry manure. This biocontrol method works best at operations with longer production cycles. Similar to parasitic wasps, pathogen-free beetles can be purchased in large quantities from a commercial supplier.

Barn application of nematodes have been relatively unsuccessful. The nematodes’ poor survival rate and limited movement makes them a less-than-optimal candidate for biological control programs for flies.”

Merck’s four-step approach for poultry red mites

- Monitor population of red mites to determine the optimal time to treat

- Do a biosecurity audit to help assure that the treatment program will be successful long term to minimize reintroduction of mites

- Treat with approved products, applied carefully and accurately

- Conduct follow-up monitoring to determine the success of the treatment, with follow-up treatment as needed.

Print this page