Production: Egg Labelling and Hen Welfare

By Kimberly Sheppard

Features Layers Production Alternative poultry housingWhat does it all mean?

What does it all mean? The pros and cons of conventional and alternative housing and moving forward

About once a week, give or take, “eggs” show up on millions of shopping lists across Canada and beyond. At one time, shopping for eggs required little more thought than adding this item to the list. Not so today. We are now presented with numerous “value-added” options, meaning the product in question has been upgraded in one form or another, and consumers have the choice of paying a premium for a product that goes beyond the standard.

About once a week, give or take, “eggs” show up on millions of shopping lists across Canada and beyond. At one time, shopping for eggs required little more thought than adding this item to the list. Not so today. We are now presented with numerous “value-added” options, meaning the product in question has been upgraded in one form or another, and consumers have the choice of paying a premium for a product that goes beyond the standard.

Today, egg cartons on store shelves may be stamped with labels such as organic, omega-3, vitamin enhanced, vegetarian, free-run, free-range, premium quality – or combinations thereof; “Cage-Free Eco-Omega 3™.” And the list is likely to grow. In a time where consumers are becoming increasingly concerned about the effects of their purchases on their health, the environment and on animals, it’s easy to become confused by the definitions of these choices, and therefore where money is well spent.

Not only does this confusion lead to difficult decision making, but decisions can be made about products without knowing the facts. This is especially applicable to welfare-added egg varieties such as free-run and free-range (alternative systems) versus the most common variety – eggs from conventional cages, which represent around 98 per cent of the Canadian table-egg market.

Before delving into some of the considerations to be made with respect to hen housing and welfare, let’s start with a primer on the most common systems. Conventional cages are commonly known as “battery cages” because they consist of tiers of batteries/individual compartments. The hens are typically kept in groups of two to six, which mimics the group size that would be established by free-roaming hens. The cage is typically made of welded wire, and the floor of the cage is sloped so the egg can roll out.

Space suggestions for the most common systems can be found in The Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets, Layers and Spent Fowl; In conventional cages, 67 square inches per bird is suggested for white (smaller) hens and 75 square inches for brown (larger) hens. Although the hens are kept in natural group sizes, the density of the group is higher than would occur naturally and the hens therefore have difficulty with fully stretching or flapping their wings or standing in an alert posture. Because the floor area is small, the hens get very little exercise.

In free-run and free-range systems the hens are not confined within a cage, but have access to the entire floor and structures within the poultry house. The hens therefore have a greater range in which to walk around, and also have access to nesting boxes and possibly perches. In free-range systems the hens also have access to the outdoors when weather permits. Free-range systems, however, have limited use in Canada due to our climate, and increase the risk of disease transmission by wild birds and animals, as well as predation.

For cage-free housing systems, the Code of Practice recommends more space per bird. Compared to space allotments in conventional cages, in free-run systems the recommended space per bird almost doubles where the flooring is all-wire or slats (132 and 147 square inches for white and brown hens respectively), and more than triples with all-litter floor systems (264 and 295 square inches for white and brown hens respectively).

For many people who learn how the majority of laying hens are housed, it seems intuitive that hens should be kept in a cage-free system where they are at liberty to perform a variety of natural behaviour. This behaviour includes nesting, dust bathing, perching, stretching, wing flapping, foraging, and walking about.

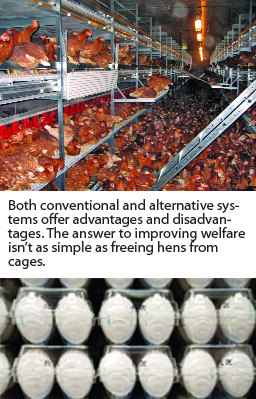

However, the answer to improving laying hen welfare is by no means as simple as freeing hens from cages. The infrastructure of today’s laying operations is complex, and includes established housing systems that have been expertly developed over the past several decades to produce eggs economically with the aid of intensive breeding, optimal nutrition, and optimal lighting programs for year-round egg production.

In fact, intensive breeding programs that have been focussed on developing hens with high egg production have changed not only production, but also hen behaviour in general. Certain “natural” behaviour may not be as important to the hen as it once was due to a highly domesticated status (think of the ways in which a Golden Retriever is quite unlike its wolf ancestors).

Likewise, other behaviour has become problematic, especially when hens are kept at the high densities of today’s production systems. A continuing demand by the general public for cheap eggs means that high hen density is a necessary component of egg production regardless of the production system employed. Even with all-litter floor

systems, which provide three times the recommended space of conventional cages, hens are housed more densely than would occur naturally.

Whereas hens kept in conventional cages remain in small stable social groups, cage-free systems house much larger groups, and hen aggression becomes a problem. Aggressive encounters can result in severe injury,

especially to hens that are more likely to rank low during attempts to establish a hierarchy.

Feather pecking can also become a problem, and can occur in conventional cages or cage-free systems. This abnormal behaviour can quickly spread throughout a group leading to high rates of injury, death and cannibalism. To help mitigate this problem, hens are usually beak-trimmed.

From an environmental and cleanliness perspective, conventional cages are typically designed in tiers, below which a conveyor belt carries manure away. Alternatively, the manure falls into a pit. This keeps the hens and their eggs

cleaner, and the hens are less likely to become diseased as a result of contact with their feces.

In cage-free systems, separation from manure is sometimes achieved by installing slatted floors. However, for hens to reap full behavioural benefits from an alternative system, there should be an area of litter on the floor for them to scratch and forage in. This litter quickly becomes contaminated with manure, which in turn contributes to higher dust, pathogen and ammonia levels in the air.

Physical health can also be affected by the production system, with hens in conventional cages experiencing a higher incidence of metabolic disorders and brittle bones due to lack of exercise, which is a severe welfare concern. In cage-free systems, bones are stronger, but a higher incidence of fractures occurs during the laying cycle.

Toe injuries and foot lesions also occur in conventional cages, due to constantly standing on a sloping wire floor, and cage-free systems result in a lower incidence of these problems. In contrast, it is more difficult for caretakers to see and attend to sick or injured birds in cage-free systems, but conventional cages facilitate this.

So, given the variety of issues associated with both conventional cage and cage-free systems, which is the better option for the hens? This is a loaded question to which opinions vary widely. One approach to answering this depends on learning which behaviour is most important to today’s domesticated hens, and therefore which elements of a hen’s environment we can forgo in the name of economics.

Firstly, housing hens with more freedom of movement and in larger groups while maintaining good welfare depends on breeding genetic strains that have lower aggressive tendencies, and on determining ways of eliminating feather-

pecking. It also depends on the willingness of consumers to pay the increased cost of eggs from cage-free systems.

In fact, research has shown that when consumers are asked if they would pay more for cage-free eggs, the majority says “yes.” However, when faced with the decision to make a purchase, they choose the cheapest option. This demonstrates that improving welfare while keeping costs low is paramount to effecting change.

Furthermore, eliminating cages may not be completely necessary if, from the hens’ perspective, all the necessary elements for behavioural expression are provided, and exercise is possible. For example, it has been found that hens in conventional cages become extremely frustrated each time they lay an egg (essentially once a day) because they do not have an opportunity to nest. This frustration is shown by agitated pacing and escape behaviour which lasts for two to four hours before an egg is laid. Providing a nest-box within the cage can solve this.

Likewise, adding well-designed perches to cages and more space for walking and standing on various surfaces improves foot health and bone strength. Foraging motivation may be satisfied by providing foraging substrate to scratch and peck at, and may help to reduce feather pecking. Adding these features to a cage system is referred to as “enrichment” and the resulting alternative cage designs are referred to as “furnished cages.”

Keeping hens in larger enriched cages also maintains the benefits of separating them from their manure which translates to healthier environmental conditions. Social groups within cages are also more stable than in cage-free systems. Health checks are easier to perform and labour is reduced, which keeps costs for the producer, and therefore the consumer, as low as possible.

In conclusion, there is no easy solution to the drawbacks of conventional cages, and alternative systems currently have drawbacks as well, although solutions are being investigated. Because consumer behaviour drives the market, however, purchasing eggs from any welfare-added alternative system sends a message to the egg industry that some consumers are willing to pay for improved welfare and provides industry with the support and incentive to continue moving toward systems that promote improved welfare more quickly.

This article was originally published in CCSAW News, the biannual publication of the Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, University of Guelph. n

Print this page