Intensive Composting Delivers Benefits

By Paul MacDonald

Features Manure Management ProductionA recent research project in Pennsylvania shows benefits

A recent research project in Pennsylvania shows that having an intensive composting system – as part of an overall manure management program – can deliver extra benefits in pest control in poultry operations

From flies to rodents, pests can sometimes be among the more serious problems facing a farm, and manure management on the farm. But for livestock operations encountering pest management problems, the solution can sometimes be as simple as developing an Integrated Pest Management plan, making it a part of the overall manure management plan, sticking to it – and sometimes sticking to it in an intensive fashion.

From flies to rodents, pests can sometimes be among the more serious problems facing a farm, and manure management on the farm. But for livestock operations encountering pest management problems, the solution can sometimes be as simple as developing an Integrated Pest Management plan, making it a part of the overall manure management plan, sticking to it – and sometimes sticking to it in an intensive fashion.

Recent research work done by extension educators Gregory Martin and Clyde Meyers from Penn State Cooperative Extension, with Paul Patterson from the Penn State Poultry Science Department, shows the benefits of not only having composting as part of an Integrated Pest Management plan, but that doing composting intensively can deliver extra benefits in pest control. The researchers found that improved poultry manure composting techniques can reduce flies and other pest populations significantly in commercial poultry production houses.

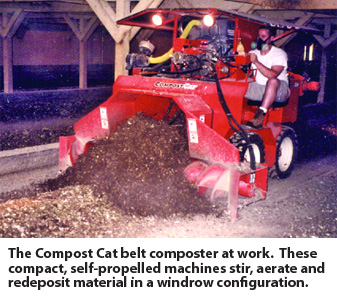

During their experiments, a mixture of poultry manure and other material – including hardwood shavings, chopped paper and straw – was mixed to create natural compost. Conducted inside chicken houses, under standard conditions, the compost was mechanically turned using a Compost Cat machine.

“By feeding the compost through the Compost Cat belt composter every two to three days, we were able to raise the temperature to an average of over 125 degrees F in some cases,” explained Gregory Martin. “The high temperatures killed the flies in the pupae stage, thus decreasing fly populations in a non-chemical way.”

Their overall goal was to increase the carbon content of the manure material and help dry the material at a faster rate, all of which takes its toll on the fly population.

Of the different types of materials, chopped straw was found to be the most effective. Chopped paper absorbed too much water, becoming lumpy. And while wood shavings were effective – lasting longer in the compost piles – the researchers found that chopped straw resulted in the higher heat profiles required to best kill fly larvae. In the trials, the paper and straw was run through a bale shredder, blown onto the manure pile, and then incorporated with the Compost Cat.

This method of composting to reduce pest populations can serve as a valuable component of a poultry producer’s overall Integrated Pest Management program. IPM aims to manage pests – such as insects, diseases, weeds and animals – by combining physical, biological and chemical tactics that are safe, profitable and environmentally compatible, says Martin.

The project was funded by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture and carried out on two poultry operations in the state. Both are commercial operations, with large housing (250,000 layers+) and manure pits. The layers were white leghorn hens, on a standard corn/soy-based diet.

While pest control is of interest for all livestock producers, it is a more pressing priority in areas that have higher concentrations of livestock production, such as Lancaster County, Penn., where Martin is located. The state still has large stretches of open rural land where ag operations are located, but development is increasingly encroaching on farm land.

“We have a concentrated population of people and concentrated ag operations in Pennsylvania,” explains Martin. “We have 300 poultry operations, 1,800 dairies and a number of horse operations in Lancaster County alone.” Considering the variety of livestock, manure handling from different types of animals is happening on an ongoing basis.

With the pace of development in the state, livestock operations – in some cases large poultry operations of 250,000 to 500,000 birds – can be in close proximity to residential sites.

In some situations, farmers – facing tough economic times – have sold off strips of their land for homes, with the owners knowing full well they are going to be living near a poultry operation.

“The problem often surfaces with the second and third owners of those houses, people who have no idea how poultry is produced in the country, and they are expecting zero dust, zero odors and zero pests,” says Martin.

Martin and his colleagues have been involved in a number of poultry litter and manure projects in the past, with this most recent project seeking to get better control over pests, specifically flies.

“It involves amending the manure while it was being composted in the poultry house. We wanted to help dry out the material at a quicker rate than you would normally see in a poultry house.”

Martin noted that they are following up on previous work done by Charlie Pitts, an entomologist at Penn State, and others showing that intensive composting can be a very effective method of killing fly larvae and pupae in manure piles.

While they understand and support the use of chemicals and additives when they are called for, the researchers were looking to encourage pest reduction through cultural practices, such as changing composting methods.

“Non-chemical practices can reduce fly numbers, and they also help keep chemical resistance down in the flies. So if someone ended up having to use chemical control, the applications are more effective because there hasn’t been a build-up of chemical resistance. It’s amazing how fast chemical resistance can build up in a fly population.”

The practical solution they have come up with is to make the environment hostile to fly breeding, at virtually no extra cost to poultry producers.

“We’ve shown through our research that it’s either break even, or that there might even be some cost savings, to go the cultural change route, even with the cost of compost turning equipment and operations.”

Martin noted that, overall, effective manure management lies at the core of any good pest management program.

“Manure is the ready medium for houseflies. By maintaining ‘good’ manure – with consistency and dryness – the environment for fly breeding is reduced considerably.

“An Integrated Pest Management program should be a part of any producer’s manure management program, no matter what kind of livestock you are talking about. Just as they are managing for livestock growth, feeding and manure management, they should have a pest management program that includes flies, rodents and any other pests that would be likely to attack their livestock.”

The lack of an IPM could mean producers are stuck playing catch-up, he noted, which has its own consequences. “Their neighbors may not be tolerant of what they are doing. If the flies get out of control, the neighbors can get very vocal. We’ve seen some farmers come under fire for the level of flies the community is experiencing.”

Martin added that with the “right” – at least right for flies – conditions, things can get out of hand in as little as a week.

“It’s that quick. If you get a sizeable infiltration of flies into your chicken house, it doesn’t take much for them to take control of the house, so to speak, especially in a wet situation where there are water leakages in the house.”

Martin tells of one particularly challenging situation. Walking into the bottom of the chicken house, he could see water dripping from above the cages into the manure pit. “The manure was so wet, it looked like a swimming pool and on the surface you could see the shimmering of all the fly larvae working through all that manure. You knew that this was just going to explode into a large outbreak of flies.”

The explosion of flies occurred and it took this farmer well over a month to get control of the house back. The water leaks all had to be fixed, the manure had to be dried as much as possible. But because the manure was so wet, it eventually had to be spread in a liquid form in an unpopulated area. “It was just like soup it was so liquid.” And all of this hardly created good relations with the neighbours.

That said, such situations are rare, Martin noted, with most producers working to be professional in terms of poultry management and land stewardship. “It’s the attitude of the producers that will make or break an operation. I’ve seen some very conscientious producers who are always thinking of Integrated Pest Management, who are always ahead of the curve, trying to predict and prevent, rather than trying to catch-up and fix problems on their farm.

“Having a predictive model is the best way to go, whether you are talking about Integrated Pest Management, disease prevention or taking care of the equipment on your farm. It’s always less costly than playing catch-up where you are always trying to fix problems that appear.”

Martin notes that it can be tough to convince poultry house operators to try the cultural methods first, before using chemicals. Operators are looking for cost-effective solutions to fly problems, and are not necessarily interested in having to perhaps hire another person to spend time handling the composting.

“It does take a certain amount of time and expertise to do this,” says Martin. “You have to train someone to do it properly, and to run the machinery, and make an investment in the machinery.”

But the payoffs are there in a reduction in flies, and also reductions in beetle and rodent populations. In the latter case, all the tilling of the compost disrupts their nesting sites.

The intense composting technique can also serve as a very effective stop-gap measure for those operations thinking of investing in new housing. Much of the new poultry housing now being built incorporates belt-type manure handling. The manure falls on a moving belt, and air flows over it, assisting in the drying of the material.

But this brand new housing requires a good deal of capital investment and for those operations looking to better handle their manure now, intensive composting represents an excellent option, says Martin.

Martin urged operators to look into incorporating carbon – wherever they can find it – to enhance and increase heat production in their compost piles.

And on a practical basis, he advised operators to get a good composting thermometer, with a long enough stem to go all the way into the compost pile and determine the temperature at the base. Martin himself uses a compost thermometer with a three-foot stem.

He also advised that if operators are not going to immediately spread compost material or manure, to cover field stacks. They used plastic sheeting in their research trials. “If there are fly larvae in the pile, when they emerge, they will be under the tarp. The sun beats down and will heat up the pile and help cook any larvae that migrate to the top. The cover acts as another composting cycle.”

This article was originally featured in Manure Manager magazine; reprinted with permission.

Print this page