Raiding the Henhouse Raises Awareness

By Leslie Ballentine

Features New Technology ProductionRaises Awareness

For some animal activists, breaking the law is a part of the job. For

others, lawbreakers make their job easier. Ontario’s farm community

recently witnessed this first-hand, after a Guelph area egg farm was

hit with three nighttime break-ins last summer.

For some animal activists, breaking the law is a part of the job. For others, lawbreakers make their job easier. Ontario’s farm community recently witnessed this first-hand, after a Guelph area egg farm was hit with three nighttime break-ins last summer. Fortunately for the Farmer, the break-ins did not escalate into serious crimes – such as the sabotage and arsons that were occurring in the area at the time. The farm was also spared costly and disruptive animal releases like the 1997 Chatham fur farm break-ins. But for the egg industry and farm community at large, the incidents should serve as a wake-up call.

For some animal activists, breaking the law is a part of the job. For others, lawbreakers make their job easier. Ontario’s farm community recently witnessed this first-hand, after a Guelph area egg farm was hit with three nighttime break-ins last summer. Fortunately for the Farmer, the break-ins did not escalate into serious crimes – such as the sabotage and arsons that were occurring in the area at the time. The farm was also spared costly and disruptive animal releases like the 1997 Chatham fur farm break-ins. But for the egg industry and farm community at large, the incidents should serve as a wake-up call.

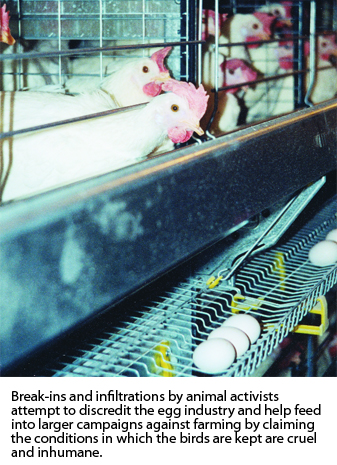

Filmed break-ins and infiltrations have been happening in other countries for several years. These illegal intrusions, done to gather evidence of alleged conditions, are publicized by activists and used for a variety of pressure campaigns and fundraising. During the past 18 months, U.S. activists have been turning their cameras on egg farms. Criminal trespass and bird thefts have been reported at farms in New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and California. So, it was simply a matter of time before Canadian activists would copy their U.S. counterparts.

As chance would have it, the Guelph break-ins came to light weeks later at an Ontario Farm Animal Council (OFAC) sponsored security conference, but only days before the raids and damning allegations made mainstream news.

The “story” first broke in a University of Guelph independent student newspaper called the Peak. Complete with photographs allegedly taken at the farm, the unidentified activists claimed the break-ins were necessary to “successfully expose the cruelty involved in Canadian egg production.” The anonymous account did not explain why vandalism and theft was also necessary but did claim a request to tour the farm had previously been denied. The target was well chosen. Not only did it involve a well-known farm that has been giving student tours for years, but the owner is also a poultry veterinarian affiliated with the University’s teaching and research community. The barn itself was an old facility slated to close in December.

The Guelph raids, as elsewhere, were an attempt to discredit the industry and to feed into larger campaigns against farming. While the break-ins most certainly occurred and police reports were filed at the time, the location of the disturbing images and alleged conditions cannot be confirmed. Accurate or not, the story served to damage the reputation of a respected veterinarian and cast the egg industry in a bad light. The damage would have been limited to a small student readership had it not come to the attention of a Canadian Press (CP) reporter or the Canadian Coalition for Farm Animals (CCFA).

A CP newswire story published a month after the Peak, reported that an unnamed student “at one of Canada’s premier animal research facilities” broke into the farm and wrote the anonymous account of “what he called a nightmarish situation involving dead birds in aisles and filthy, defeathered birds in cramped cages.” The inflated story went on to say that the student later said his “undercover investigation,’’ was modelled on similar ones done in the U.S.

The story continued that “the break-ins provided a rare look at what activists claim are the hidden horrors of egg barns in Canada,” saying they are no better than those in the United States despite industry claims to the contrary. The CP story ran days after the well-publicized ruling by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission against the U.S. industry’s “Animal Care Certified’’ seal on egg cartons. A ruling that came after alleged footage of U.S. egg barns was used by activists in a formal complaint that “the label misled consumers concerned about cruelty to hens.”

The allegations continued when Canadian Coalition for Farmed Animals and Vancouver Humane Society spokesman Bruce Passmore told media the photographs showed “standard conditions.” This despite his admission that members of his animal rights group have never been allowed into egg barns during their regular operations. Passmore also said his organization was convinced of the images’ authenticity. However, the organization had no information on the identity of the individual who obtained them, he said.

Several days following the CP coverage, a poorly attended press conference was held in Toronto. The CCFA called the conference to promote the still and video footage allegedly taken during the break-ins, and to ramp up their two-year campaign to force retailers to label eggs that come from caged hens.

Most journalists correctly chose to not run a story since the allegations were made anonymously and could not be substantiated. Even PETA celebrity spokeswoman, Pamela Anderson, couldn’t jumpstart media interest when she was pulled in to lend her name to the campaign. In fact, the story received far more coverage in the farm press than it did in the mainstream media. However, the footage, accompanied by an “Investigative Research Report” has been posted on the CCFA website for the Internet world to see.

Little did the farmer know that his break-ins could make the headlines or web pages. And had he let his commodity group know at the time, he might have saved himself many added troubles. Not only could the industry have provided earlier assistance, but his industry partners would have also been better prepared to respond.

Sometimes it might seem that an incident is not worth reporting. With growing rural crime, incidents are sometimes not taken as seriously as they might be. Even if an incident is reported, it can be hard to get police to come out to investigate. And when they do, activist incidents can be overlooked as unconnected crimes. That was what happened in this case. It took those in the industry to connect the dots, but not before the damage was done. The break-in shows the importance for producers to not only report to local police, but also to their commodity organization and farm animal council.

Sharing information along with on-farm security can also help to prevent activist crimes. In the U.S., producers run their own Neighbourhood Watch program. This centralized national reporting system for on-farm incidents has proved valuable both for farmers and police investigators. Suspicious requests for tours along with suspicious visitors and any illegal activity such as vandalisms and break-ins should always be reported promptly.

That’s because what happened at the farm may happen to someone else and could even happen again at the same farm. Crime, animal disease threats and, now, activist actions are all good reasons for on-farm security. Locking barn doors and having good security measures can go a long way in deterring unwanted visitors.

Despite the concerns, farmers will and should, continue to offer public tours and to keep the public informed. People don’t need to use illegal methods to find out what happens on

our farms.

Leslie Ballentine served as the founding executive director of the Ontario Farm Animal Council (OFAC) and is a former communications specialist with Egg Farmers of Ontario.

She now runs Ballentine Communication Group specializing in issues research and analysis and strategic communication consulting. She has 20 years of experience in dealing with animal welfare and animal rights issues.

This article first appeared in the February 2006 edition of OFAC Outlook, the quarterly newsletter published by OFAC.

Print this page