Sunrise Farms

By David Schmidt

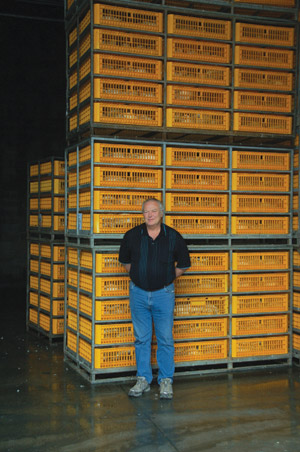

Features Profiles ResearchersPeter Shoore’s processing plant in Western Canada

How did a Vancouverite of Scottish heritage who studied classical music

in the Netherlands for seven years become an icon in the Canadian

chicken industry?

“Fate” says Peter Shoore, who is celebrating the 25th anniversary of

Sunrise Farms, formerly called Sunrise Poultry. “It’s a case of being

in the right place at the right time.”

|

With a knack for the chicken processing business and the right timing,

Peter Shoore has built the largest individual chicken processing plant

in Western Canada

How did a Vancouverite of Scottish heritage who studied classical music in the Netherlands for seven years become an icon in the Canadian chicken industry?

“Fate” says Peter Shoore, who is celebrating the 25th anniversary of Sunrise Farms, formerly called Sunrise Poultry. “It’s a case of being in the right place at the right time.”

After earning his doctorate in music in the mid-1970s, Shoore decided to return home rather than remain in an overcrowded Europe. Deciding he couldn’t make it as a classical musician, Shoore went to work in his father’s small cannery where, among other things, he canned whole chicken.

That led to an offer from White Spot, a chicken-based restaurant chain then owned by General Foods, to run their small money-losing chicken processing plant in Surrey, B.C. He was an instant success.

Peter Shoore has increased capacity at Sunrise Farms from 25,000 to 600,000 birds/week, including a hatchery, further processing plant and a massive live haul fleet to the operation.

|

“It clicked with me,” Shoore says. “Operating a chicken processing plant turned out to be something I was really good at.”

The plant was located on leased property, with the lease set to expire in early 1983. After General Foods made a failed half-hearted attempt to buy the property, Shoore was prompted by his mother to make an attempt of his own.

It was the first of many “gutsy moves” Shoore has made over the past 25 years. In fact, his holding company is fittingly called “High Noon Enterprises.” (Shoore’s various operations are structured as separate companies, which are in turn owned by the holding company. “My employees are on profit-sharing plans and I only want them to benefit from the company they’re directly involved in rather than the whole operation,” Shoore explains.)

When the lease expired, Shoore simply told White Spot, which itself was in the process of being sold and which remains one of his customers, the lease would not be renewed, effectively daring them to remove their equipment. They didn’t – selling it to him instead.

At the time, the plant was about 20,000 square feet and killed about 25,000 birds/week. It has since grown to 120,000 square feet and now kills over 600,000 birds/week.

While still number three overall in British Columbia. (Lilydale and Hallmark are both bigger processors), Sunrise’s Surrey plant is the largest individual chicken plant in Western Canada. Shoore’s operations also includes a hatchery in the Fraser Valley, a former beef plant which is now used primarily for packaging and storage, a further processing plant in Abbotsford, a massive live haul fleet and, most recently, a hatchery and processing plant in Lethbridge. Among them, the various operations employ about 1,000 people. Shoore also owns three broiler farms in the Fraser Valley.

Shoore admits his timing to get into the business couldn’t have been better, displaying the B.C. Chicken Marketing Board’s annual production graphs to prove it. After flat production in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the market “went stupid” in 1983. Production has increased almost every year since and is now triple what it was 25 years ago.

Others may call it lucky, but Shoore prefers to think “we created the wave.” Unlike many others, he thinks the end is not yet in sight.

“We see a lot more growth in raw,” he says, “it would require looking for new markets but the will to do that doesn’t seem to be there in Canada.”

While he recognizes feed prices have skyrocketed and are putting the brakes on growth, he believes that is only temporary. He insists the increased feed costs are actually good for chicken, saying “the more expensive feeds become, the more reasonable chicken becomes.”

He points out that not only is chicken a much more versatile meat, meaning it can be used in a wider variety of dishes than beef or pork, but it takes only two pounds of feed to produce a pound of chicken, as compared to four pounds of feed for a pound of pork and eight pounds of feed for beef.

“Our company is always pushing for more growth. Eventually the hog price will go up and when it does, a lot more chicken will be required.”

Because chicken supply is so tightly controlled, he decided “the only way for us to grow is through further processed.” He therefore built his further processing plant. His forseight was justified: Opened in 1997 with one line, it now operates three cooking lines. The products are sold in both retail and HRI (hotel, restaurant, institutional) markets across Canada.

Shoore sees an opportunity to grow the business in the further processed and raw markets.

|

The further processed plant is just one of Shoore’s innovations. In 1991, Sunrise was the first processor in Canada to go to a tray-catching system, which is not only used with automated catching machines but also allows automated loading of the killing line.

Shoore has seen tremendous change in the past 25 years, not the least of which is change in the chicken itself. When he started, chicks were sexed and it took cockerels 6 weeks and 3 days and pullets 7 weeks and 3 days to reach 3.8 pounds live weight. Today mixed flocks reach the same weight in just 32 days.

“If we sexed the birds, we could probably bring cockerels in at 28 days,” he states, adding he expects production time to continue to shorten a day/year for the next five years. “We now worry about the size of chick which goes to the barn and the actual time it gets delivered and later picked up.”

While he has faced few adversities in his 25 years, Shoore admits he was stumped by when the avian influenza outbreak hit in 2004. “That was my most difficult time in the industry because I literally didn’t know what to do. I left it up to my managers and they decided to bring in birds from outside. It was logistical nightmare but it worked.”

While AI was an expensive lesson for all sectors of the industry, Shoore doesn’t believe the lesson has been learned.

“I don’t think anyone has done a good enough job of preventing another recurrence. Producers don’t have any better biosecurity now.”

While AI remains a huge threat, urbanization may be an even bigger threat. It not only faces farmers, whose practices are under siege by increasingly urbanized neighbours, but also the processing plants whose once relatively isolated locations are now surrounded by more upscale “clean” industries and even urban residences. Yet Shoore does not relish the prospect of moving.

“If they told (the processing plants) tomorrow we were gone, where would we find land with adequate water and sewer?” he asks.

Shoore admits B.C. processors and B.C. producers continue to have a running battle over price, but has little sympathy for complaints that grower returns are insufficient.

“The fiscal year of our own farms ended in April and we had a record year,” he claims.

He suggests producers having a tough time making it should look inward. “I see returns from a good producer to a bad producer are quite different. There is also a big discrepancy between feed companies. Producers need to put more pressure on there.”

After 25 years in the business, Shoore is giving more responsibility to his upper management and starting to groom his son to take over.

“He just finished his first year at the University of the Fraser Valley and we want him to get an MBA.”

His son is also learning every aspect of the business.

“He has worked on the catching crew, done chores on the chicken farm, done all the jobs in this plant and is now working in the hatchery.”

But that doesn’t mean Shoore intends to quit the business anytime soon. “I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I retired. I hope they carry me out of here.”

Print this page