Technology: The ‘Crackless Egg’

By Treena Hein

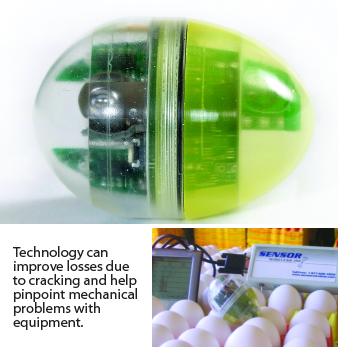

Features New Technology ProductionTechnology can improve losses

Real-time wireless sensor technology provides instant identification of trouble spots that cause cracking on egg farms

Having a way to easily and immediately measure im-pact jarring of eggs as they move through the barn in order to minimize cracking may seem to some farmers like a far-away dream. However, several Canadian poultry producers are using the Crackless Egg,™ a technology created by Sensor Wireless Inc. of P.E.I., to make that dream a reality.

Having a way to easily and immediately measure im-pact jarring of eggs as they move through the barn in order to minimize cracking may seem to some farmers like a far-away dream. However, several Canadian poultry producers are using the Crackless Egg,™ a technology created by Sensor Wireless Inc. of P.E.I., to make that dream a reality.

Simply put, the Crackless Egg mimics a real egg in shape, size and weight as it travels from the chicken to packing tray, ready for shipping. Travelling along conveyor belts and elevators alongside real eggs, the Crackless Egg wirelessly transmits immediate real-time data on the level of impact it receives to the farmer via a hand-held device. (The technology can also measure other factors such as temperature and pressure.)

The hand-held displays a graph indicating every instance the Egg receives an impact jar above a given threshold versus time, allowing the farmer to make immediate adjustments that decrease the jarring real eggs receive. This data can later be downloaded to a computer for permanent record keeping, if desired.

Darryl Drain, Farm Manager at Drain Poultry in Tweed, Ont., is “very pleased” with the Crackless Egg they purchased in spring 2007. He says “Even in our best barn, we lowered our reject rate. I didn’t believe that was possible.” In addition to using it on an ongoing basis at their two operations (55, 000 birds total), Drain says they are also using the Egg to guide them in completing upcoming renovations. “We have three types of cages,” he says. “We wanted to try and see which system is giving us the best results.” The system indicated by the Egg as “worst” will be renovated first.

Drain says that although he would rather answer the question of financial savings due to the Egg once he has a year of records, he says so far it has provided a 0.5 per cent or better reduction in cracking in every barn. “In the long run,” he says, “that saves a lot of money.”

Chris Monden, who raises more than 61,000 layers at his Unicorn Farms near London, Ont., calls the Crackless Egg “a great investment because it goes on forever.” Monden has been using the Egg for about two years, and says that adjustments he has been able to make because of Egg feedback have improved his average losses of 3.2-5 per cent by a minimum of 0.25 per cent every flock run. “That’s very significant,” he says. Monden also believes the Egg will become even more important as his equipment ages. “That, to me,” he says, “is where it really will make the

difference.”

Gray Ridge Egg Farms (L.H. Gray) of Strathroy, Ont., first purchased an Egg in 2003, and then traded it in 2006 for a newer model. Leanne Cooley, poultry nutrition specialist, and Bill Wareham, producer relations, say “The overall operation and performance of the Egg has been very good.” They add “It is fair to say that there is benefit, not only to established operations, but also to those setting up new cage and conveying equipment, making adjustments on timing, or installing mechanical egg packers. There are numerous applications.” Gray Ridge also has future plans to use the Egg in grading operations. “We did not initially believe this to be possible,” say Cooley and Wareham. “However, Dave McNally [Agricultural Sales Specialist at Sensor Wireless] suggested that exposure to wash water would not affect performance of the Egg.”

In terms of measurement of savings, Cooley and Wareham say, “We have always kept a close watch on trends from flock to flock. The Egg provides a tool for us to not only react to a ‘spike in cracks’ as we call it, but also to proactively perform routine checks on equipment and identify issues before they become a significant problem. Quantifying value from proactive maintenance is challenging.” They also find it difficult to generalize about savings in older versus newer equipment, but do observe that “issues such as timing of egg transfers can cause cracks in [either].”

SPECIFIC ADJUSTMENTS

Drain says that he can best sum up what the Egg means to his operation by saying “It gave me eyes of a different sort and took off my blinders … In our best barn, the newest, I found some things that hadn't been maintained. You look at the machines in a different way. We found some other things that were very simple to fix, things we weren't looking for.”

One situation identified by the Egg that especially stands out for Drain involved a wire out of place, resulting in eggs on a belt “getting smacked by other eggs.” He says “I don't know how I would have found out about it. This would have gone on for possibly a long time …That saved us some money right there. We might have noticed, but it was quicker with the Egg.”

Monden has found that his Egg picks up on potential jarring problems at three points along conveyors and elevators before moving into the packing machine, where there are four more potentially problematic transfer points before the eggs go into trays. “You can’t always see these points,” he notes, “or you can see these points, but can’t always tell what the stresses are.” Monden says he makes immediate adjustments such as adding foam for cushioning or slowing transfers. He adds that using the Egg is critical in minimizing impact every time he gets the conveyors and elevators running again as he sets up for each new flock. “I run it through as a set-up precaution and then use it two to three times per run,” he says.

Cooley and Wareham say, “The instant data provided by the Egg permits rapid identification of areas or equipment requiring maintenance. Maintenance is typically conducted at the time a problem is identified, and then the Egg is used again to verify the effectiveness of the repairs or modification.”

COST RETURN, CHALLENGES AND TECHNICAL SUPPORT

Although determining cost return is not easy for Drain at this point, having used the Egg for only about six months, he estimates it as “probably two years.” He says he saved a bit by buying his Egg at a farm show. Monden says he will achieve cost return for his Egg in under five years. Cooley and Wareham say, “Our cost return is not the determining factor when we evaluate the success of this product. Our goal is to provide service to the producer and to provide the best quality product to the consumer.”

In Drain’s opinion, an egg farm needs to be a certain size to make purchase of an Egg cost effective. Monden agrees: “If you have 30, 000 birds, it’s well worth it.”

Although he has had no problems in Egg operation, Drain warns that you can’t just unpack the technology and finish a proper assessment in 10 or 15 minutes. “You need to separate some time just to do it,” he says. “It took three hours or so to go through each row and section, with 12 rows per barn.” Drain adds that the Egg features many more data management and analysis features than he would ever use. n

Print this page