Poultry vaccination developments

By Treena Hein

Features Breeders Broilers Layers TurkeysNew efforts to shorten the withdrawal period and other emerging issues.

Shortening the withdrawal period for infectious laryngotracheitis vaccines has been a hot topic in Canada for the last few years.

PHOTO CREDIT: Markus Spiske, Unsplash.

Shortening the withdrawal period for infectious laryngotracheitis vaccines has been a hot topic in Canada for the last few years.

PHOTO CREDIT: Markus Spiske, Unsplash. At this point in time, infectious laryngotracheitis (ILT) is more of a struggle for broiler producers in Canada than it is in other nations, and experts say that’s due to the current vaccination situation. In December and January, there was a small epidemic of ILT in the Niagara region of Ontario, but ILT is a disease that poultry producers across the country have to face each year.

The virus can lurk in barns, be spread in many ways between farms and can also appear on a farm when older chickens become stressed. That is, the virus is carried in the birds’ bodies in a dormant state, similarly to the herpes virus in humans, and if a particular bird is stressed, the virus can become active in that bird, be shed into the environment and spread. All of this makes eradication of the disease difficult.

Vaccination is an excellent way to manage the disease, but change needs to occur for that strategy to work. At the hatchery, it’s not standard practice in Canada to vaccinate day-old broiler chicks for ILT, as it’s expensive and may be unnecessary. At the broiler or layer farm, if infection in a flock is a concern, birds can be vaccinated on or after 17 days of age, a point in time when maternal antibody interference no longer has the potential to make the vaccination ineffective.

However, right now in Canada, the withdrawal period is 21 days (as it is for all other poultry vaccines). This conflicts in broilers with the processing point, typically at 34 days but it can also occur a few days before that. Experts say the withdrawal period, therefore, needs to be reduced, as it has been in other countries.

Indeed, shortening the withdrawal period for ILT vaccines has been a hot topic in Canada for the last few years. Control of the withdrawal period falls under the purview of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). “What CFIA has told the industry is that it follows the U.S. government on this issue, but the U.S. industry is not interested [in a shorter withdrawal period] because flocks there are processed at least around 42 days of age versus most Canadian broiler flocks at an average of 34 days,” explains Babak Sanei, manager of veterinary services for poultry and medicated feed additives at animal health firm Zoetis. “There is no robust data to show where and how this 21-day period was initially adopted.”

Canadian Animal Health Institute (CAHI) president Catherine Filejski adds that the 21-day withdrawal period policy was likely initially implemented in Canada because the majority of veterinary vaccines used here are imported from the U.S. She notes, however, that although “there has been little pressure” within the U.S. to change the regulation there, “this situation is beginning to change.”

Steve Leech, director of food safety and animal health at Chicken Farmers of Canada (CFC), explains that “similar vaccines have a zero-day withdrawal in the European Union, Australia and New Zealand.” CFC has requested that CFIA review the 21-day withdrawal period because, as Leech explains, it’s “an arbitrary number, and is now causing issues as the industry tackles animal health, welfare, pathogen and antimicrobial use reduction strategies.”

Vaccination of adult birds for ILT aside, the 21-day vaccine withdrawal period that now exists in Canada also prevents the administration of a vaccine booster, required for many vaccines at about the 20-day mark. One example of this is the booster for the infectious bursal disease (IBD) vaccine. “A booster would be given at day 18 to 21,” Leech explains. “Without the booster, immunity is lowered and flocks can break with IBD and have secondary infections in the week or two prior to shipment.”

Progress towards a solution

At the beginning of 2021, CAHI launched its Priority Animal Health Needs (PAHNs) initiative, aimed at identifying species-specific needs for veterinary products (including vaccines), barriers (regulatory and otherwise) to making these products accessible to Canadian producers and innovative solutions to improve accessibility. PAHNs also aims to develop the partnerships between the animal health industry, the veterinary community and commodity sectors to better understand how regulatory burdens are impacting animal health and welfare in Canada, and the creation of opportunities for veterinarians and commodity groups to voice concerns.

“PAHNs will also be an ongoing CAHI initiative,” Filejski says, “with annual identification of priority needs for products, which will also serve to track changes and trends in both health needs and product availability for our stakeholders and our regulators.”

For the poultry sector, CAHI has requested input from the Canadian Association of Poultry Veterinarians (CAPV) on priority health needs for all poultry species. Once that input is consolidated, CAHI will reach out to producer associations to obtain their input and then gather information from CAHI’s member companies on the barriers to registering these products in Canada.

Filejski says initial discussions with both Health Canada’s Veterinary Drugs Directorate and the Canadian Centre for Veterinary Biologics (CCVB) of CFIA have yielded enthusiastic support for the PAHNs initiative, and confirmed the commitment of leadership in these organizations to find innovative approaches together.

However, Filejski says, “A high priority need for vaccines with a 0-day withdrawal period was identified before the PAHNs initiative was even officially launched.” This would reduce antimicrobial use, result in better health for Canadian flocks, increased food safety through better control of zoonotic pathogens such as Salmonella, and improved competitiveness for Canadian poultry producers. Discussions about a path forward, involving CAHI, CCVB, CAPV, CFC and vaccine companies, are slated to start in the coming weeks, Filejski says. “Stay tuned to CAHI for developments.”

Innovative teaching tool

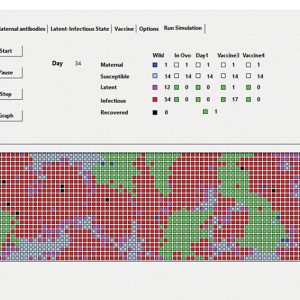

Quebec veterinarian Robert Charrette is now updating a simulation tool he created for farmers, veterinarians and others that highlights the effect of vaccination timing and more on broiler immunization success. He developed the tool many years ago with data and concepts from Daniel Venne, CAPV co-director and director of poultry health at Quebec poultry company Couvoir Scott. The tool has been used in presentations in other countries as well as in Canada and was presented at the World Veterinary Poultry Association Congress.

On the screen, users can see various flock simulations that show how vaccination (the act of giving vaccines) does not necessarily equate to immunization (effective vaccination). Many factors, as seen in the tool, can affect vaccination success, including quality of barn cleaning between flocks, level and uniformity of maternal antibodies within a given flock, use of different vaccine types, vaccination timing, biosecurity breaches and more, for diseases such as infectious bursal disease (Gumboro) and ILT.

The tool clearly demonstrates how vaccination at 19 to 21 days (if the 21-day withdrawal period is shortened) would help with immunization effectiveness in Canadian broiler flocks, which generally have high level of maternal antibodies. Those wanting to see the simulation should contact Charette at robert.charette.mv@gmail.com.

Other vaccine developments

In terms of additional vaccine concerns in Canada, Leech notes that development for a necrotic enteritis vaccine is a top priority, both for industry antimicrobial use reduction and pathogen reduction.

Filejski adds that additional poultry vaccine needs in Canada are in the process of being formally identified through PAHNs. “Initial input has indicated a need for protectotype approaches to vaccination against infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) to reduce the level of IBV disease in chickens in Canada,” she says. “A variety of IBV vaccines currently commercially available in the U.S. cannot be brought into Canada because these are live vaccines. Again, stay tuned for more.”

Print this page