Blast from the Past

By Jacob Biely University of British Columbia

Features New Technology ProductionFrom Canada Poultryman, August, 1937. Originally entitled “The Use of Batteries”

The use of cages for poultry has been much in the news in recent years. Seventy-three years ago cages were also making news, but in a very different way.

The use of cages for poultry has been much in the news in recent years.

Seventy-three years ago cages were also making news, but in a very

different way.

|

| Photos from our august 1937 Canada Poultryman issue: The above photo had the original caption “you get clean eggs from battery layers.” In 1937, cages were not used on a commercial scale in Canada but were utilized in England and parts of the U.S. Advertisement

|

In recent years a new interest has been created in the management of laying hens through the use and adaptation of laying cages. This means, of course, that each bird is confined to an individual coop throughout the laying period. This practice is radically different from the old established custom of keeping hens in flocks and of at least giving them the freedom of the poultry house and yard. While the laying cage system is not common, as yet, on commercial poultry farming in this country, it has been practised to a considerable extent in England and certain sections of the United States for some years. A number of large plants of more than 1,000 birds are in operation in the state of Washington, whereas several smaller commercial units are being established in this province.

Of course, the idea of individual coops or cages for laying birds is not by any means a new or recent one. They have been used for experimental purposes for many years at different research stations.

A good many birds, utilized for experimental work at the University of British Columbia, have been successfully kept in cages for months at a time. In each case, satisfactory egg production has been obtained when the birds have been fed a balanced ration.

DAY OLDS TO EIGHT-WEEK-OLDS

During the past seven years several thousands chicks have been raised up to eight weeks in battery brooders at the Poultry Nutrition Laboratory of the university. Without these brooders it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to conduct feeding tests. In many instances, depending upon the type of ration used, the growth and health of the birds so raised have been excellent. In fact, in one experiment an average weight of more than 1.75 pounds was obtained in Leghorns at eight weeks. Furthermore, the mortality was lower than that of two per cent of the baby chicks started in the batteries. Contrary to popular opinion, the chicks confined to the battery brooders have not shown any toe or feather picking.

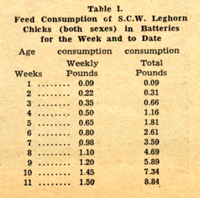

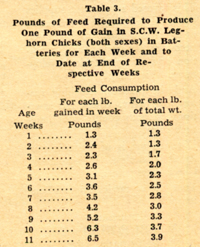

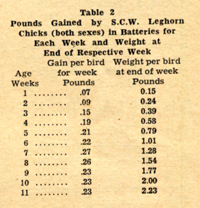

The average weight of chicks reared in the battery brooders is generally higher than that of chicks reared under ordinary commercial conditions. Feed consumption and growth of White Leghorn chicks raised in batteries are shown in the original published tables 1-3 on page 45.

CHEAPER TO RAISE PULLETS

The problem of carrying through in batteries pullets from six to eight weeks to the laying stage is somewhat complicated, involving as it does the use of expensive equipment and accommodation and special management. For these reasons young growing pullets can be more economically and more easily raised on grass range.

|

| Cover from our august 1937 Canada Poultryman issc

|

With the approach of fall, or as soon as the pullets begin to show sexual maturity, they are transferred to laying cages. The laying pullets are kept in cages as long as they are productive, or until they go into a natural moult the following fall.

Year-old pullets that have been laying well throughout the year are, as a rule, allowed to moult under natural conditions. Upon completion of the moult, the yearling hens are returned to the laying batteries. However, on some farms, the moulting pullets are handled as potential breeders; i.e., they are given eight to 10 weeks to recuperate and are allowed free range. Following such treatment the birds go into the breeding pen in apparently splendid condition. The results in many cases have been quite satisfactory from the point of view of fertility, hatchability and livability of chicks. Whether this practice can be successfully carried on year after year remains to be seen.

CONFINED BIRDS CONTENTED

There is considerable difference of opinion regarding the general use of battery cages. It may be said without contradiction that those who have had personal experience with cages are, on the whole, very well satisfied with them. In many cases egg production is reported to be comparatively higher in the laying cages than when the birds were allowed the freedom of the house. Furthermore, it would seem, from personal observation, that controlled pullets are just as contented as those kept under ordinary conditions.

|

| In the August 1937 issue of Canada Poultryman this was deemed the “Laying House of the near future.” It would feature central heating and air-conditioning.

|

Within the last two or three years the practical possibilities of laying cages have been amply demonstrated. The successful management of birds in laying cages is now a matter of acquiring experience and of applying common chicken sense. It must not, however, be thought that the laying cage system runs itself. On the contrary, it requires more careful planning and attention than does the ordinary laying-house system.

The pros and cons of laying cages for large-scale commercial poultry farming are at present a lively subject for discussion in the English poultry magazines. Considerable interest in this phase of the poultry industry is now being shown in British Columbia. An interesting commercial exhibit is being planned for showing at the next Canadian Pacific Exhibition.

Cages for backward birds

The writer believes that laying cages could be usefully employed to a limited extent on all commercial poultry farms as a supplementary means of salvaging individual birds that ordinarily would be neglected and eventually discarded from the flock. Birds that are “off condition,” timid or underdeveloped in comparison with their mates; birds that are suffering from prolapsis, pick-outs, feather picking or bruises; and birds that are affected with chronic coccidiosis, roundworm or tapeworm infestation, etc., would be better off if segregated from their penmates. In the laying cages they could be individually conditioned or treated and, upon recovery, returned to the general flock. It is remarkable indeed how quickly the birds respond to treatment when confined individually. If kept in laying cages they are completely protected from abuse by other birds and have free access to feed and water with very little exertion.

A bird that is off condition is not likely to fight its way to the mash hopper or water trough to get its share, or to look to scratch grain in the litter, or to get the required amount of green feed, shell and grit from self-feeding hoppers. These, and other difficulties, are obviated when the bird is confined to the laying cage, where it may have a chance to recover instead of huddling itself in or being driven to some corner of the house and gradually wasting away.

The problem of mortality and excessive percentage of culls is at present of the greatest significance to the poultry industry. It would seem possible to curtail some of these losses through the use of laying cages. In the writer’s opinion the average commercial poultry farmer could make good use of laying cages for the purpose described above, viz., as an aid in securing greater efficiency from his flock through the salvage of birds that otherwise might be a total loss.

|

|

|

Print this page