Easing the transition away from antibiotics

By Lilian Schaer

Features HealthGut health programs aid shift to antibiotic-free broiler production, new study shows.

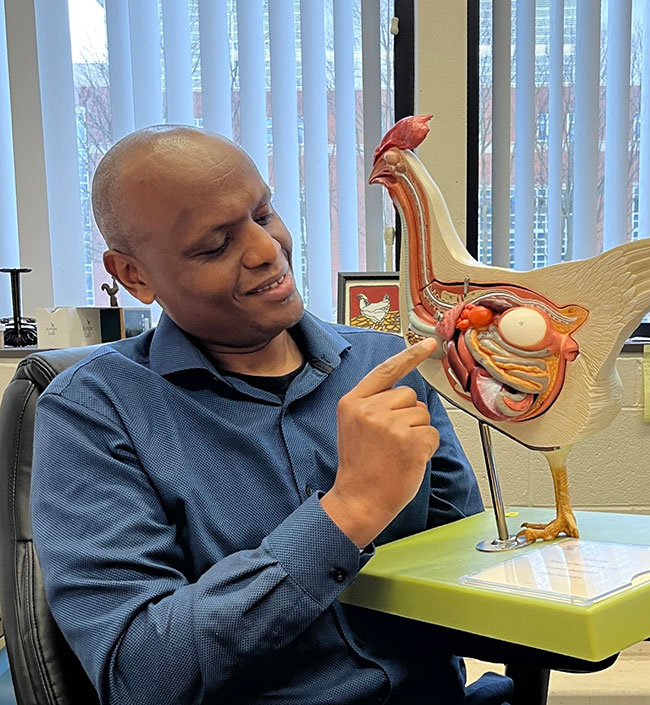

University of Guelph researcher Elijah Kiarie co-led a study with Lisa Hodgins, monogastric nutrition manager at New-Life Mills, evaluating commercially available gut health programs for broilers.

PHOTO CREDIT: Elijah Kiarie

University of Guelph researcher Elijah Kiarie co-led a study with Lisa Hodgins, monogastric nutrition manager at New-Life Mills, evaluating commercially available gut health programs for broilers.

PHOTO CREDIT: Elijah Kiarie New research from the University of Guelph shows that broiler chicken producers can transition to production systems with minimal or no antibiotics without impacting bird performance.

Given global concerns around antimicrobial resistance, Canadian poultry producers are adapting their production practices to meet mandated reduction and elimination of antibiotics that have long been used in production.

Gut health programs are seen as key in maintaining bird health and performance when antibiotics are no longer used or used to a lesser degree. But a lot is still unknown around how different feed additives perform in commercial settings.

Elijah Kiarie, associate professor of monogastric nutrition in the Department of Animal Biosciences at the University of Guelph and holder of the McIntosh Family Professorship in Poultry Nutrition, and Lisa Hodgins, monogastric nutrition manager at New-Life Mills, led the research that evaluated commercially available gut health programs for broilers to gain a better understanding of what impacts they have on birds.

“So many feed additives claim to have health benefits, but when you go to industry, everyone has a lot of questions. Generally, we only test one additive at a time, but producers will often use them in combination,” Kiarie explains. “So, we want to know how they interact, how can we help industry navigate these changes and is the feed we are providing viable.”

“Commercial nutritionists like me are challenged to create gut health management programs that use less or no antibiotics – and gut health programs are even more important now,” Hodgins adds. “So, we were looking to benchmark growth and performance of birds reared on commercial gut health programs, and measure their performance, gut physiology, plasma biochemical profiles, and bone attributes.”

Three programs evaluated

As part of the project, the research team evaluated three commercial gut health programs that represent most of Canada’s poultry production: conventional; raised without medically important antibiotics (RWMIA); and raised without antibiotics (RWA).

In the conventional program, some use of antibiotics designated as medically important to human health is allowed. The RWMIA program allows no use of medically important antibiotics and the RWA program allows no use of antibiotics of any kind.

The first significant trial of the three gut health programs was carried out on nine commercial broiler farms in Ontario, starting in May 2019 and continuing to June 2020. Three commercial farms were assigned to each gut health program and each farm was followed for six consecutive flocks. In total, 1.15 million birds on commercial farms were part of the project.

The same three programs were evaluated in a research setting at the Ontario Poultry Research Centre at the University of Guelph’s Arkell Research Station from late March to May 2020. Here, 2,304 male and female birds were followed from placement to day 42.

In both the commercial and research settings, birds were fed commercially available three-phase feed programs for starter (0 to 14 days), grower (15 to 28 days) and finisher (day 29 to slaughter) periods. Diets for RWMIA and RWA flocks were supplemented with butyric acid and a bacillus-based probiotic, and RWA diets also contained fumaric acid, dehydrated yeast, yeast products, thymol, eugenol and vanillin.

“All three programs used enzymes and products that are commercially available and would be used by feed companies,” Hodgins notes.

The researchers observed some differences in breast attributes, plasma metabolites and gastrointestinal responses. But, overall, birds on all programs showed similar performance. This illustrates that gut health programs are effective at maintaining bird performance and that any identified differences did not impact that performance.

“The bottom line for producers is that you can go into production without antibiotics,” Kiarie says. “The alternatives work if you want to make that transition.”

Complementary strategies

What’s important though, is that producers think not just about the additives but the entire diet, including the sources of any nutrients or the quality and type of feed ingredients that are used. And when antibiotics are removed as a tool, farm management also becomes a critical factor in the success equation.

Antibiotic use reductions and restrictions will continue, so producers should consider using complementary strategies in their search for alternatives. This is best done by producers working in tandem with their processor, nutritionist, hatchery representative and veterinarian to pick the best program for their particular farm, recommends Hodgins.

According to Kiarie, this is also where applied industry research with farmer involvement is critical to helping find and expand solutions. True commercial farm conditions can’t be properly replicated in a research setting, for example, and stresses flocks are exposed to in these two situations are different in each setting.

“This was a very unique aspect of this project. Lisa has proven that farmers can be partners in research – the cost of this project was not really different from any other research even though it was much bigger with respect to the number of birds involved,” he says. “We would like to see more of this and will continue to pursue these kinds of opportunities.”

Further research needed

The rations used in these trials were corn-based and with antibiotic restrictions applying to all producers across the country, there is a need for more research focused on wheat as an ingredient.

As well, Hodgins believes, future research should also investigate gut health programs using animal proteins, fats and blood meal, and vitamins coated in gelatin – all of which are restricted under RWA programs currently.

“If we can’t use these products in rations, how will we use them in the future? Will they go into landfill, for example?” she asks. “There is also the sustainability question to consider here.”

The research project was funded by the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance (formerly the University of Guelph – Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs partnership), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Centre Discovery Program.

Print this page