Healthy hearts for healthy birds

By Lilian Schaer

Features Health BroilersScientist employs innovative approaches to advancing cardiovascular health in broilers.

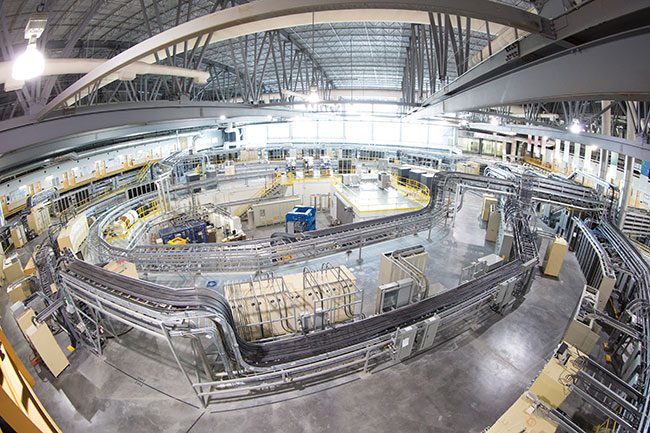

For his latest research, Andrew Olkowski worked with the Canadian Light Source synchrotron at the University of Saskatchewan to take a closer look at the proteins in the hearts of broilers. PHOTO: University of Saskatchewan

For his latest research, Andrew Olkowski worked with the Canadian Light Source synchrotron at the University of Saskatchewan to take a closer look at the proteins in the hearts of broilers. PHOTO: University of Saskatchewan Next to infectious diseases, heart failure has become a leading cause of sickness and death in broiler chickens. With improvements in genetics and nutrition, modern broiler chicken strains are growing to larger market weights and reaching those weights much more rapidly than before, putting increased stress on their health.

According to research by Andrew Olkowski, Scientist Emeritus in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan who has studied poultry heart health for decades, healthy hearts are key to healthy birds.

In addition to direct bird mortality, he suggests heart problems could be underlying causes of other poultry health issues related to muscles, bones and skin, impacting bird welfare and, ultimately, farm profitability.

“Fast-growing chickens are highly susceptible to heart failure, which is actually heart pump failure,” he explained during a presentation at the most recent Poultry Research Impacts Day hosted by the Poultry Industry Council. “Anybody involved in broiler production will have seen the signs of heart failure.”

Early symptoms of heart problems include cyanosis, which is a clinical sign shown by bluish discolouration of the comb. Birds with more advanced cases will show ascites or what is commonly called water belly – an accumulation of fluid in the abdomen.

Earlier work

In early studies, Olkowski used echocardiograms to examine and compare hearts of normal birds and those with heart failure. He found dramatic differences in the function and anatomy of the left and right ventricles or heart chambers.

He also found microscopic lesions on the small fibres responsible for contracting the heart and changes in the mitochondria, which supply the chemical energy for the heart to perform properly.

“The direct effects of heart pump failure are decreased cardiac output, which translates into poor blood oxygenation and poor blood circulation,” he said. “In the end, it is decreased oxygen delivery to the organs (of the chicken).”

Multiple studies led by Olkowski into the prevalence of heart failure in the broiler chicken population ultimately concluded that, whether they display visible symptoms or not, between 20 and 30 per cent of broilers may be affected by heart pump problems.

When he first began working in poultry research in the 1990s, heart health was a key priority for the industry due to high mortality from sudden death syndrome and condemnation rates as a result of ascites associated with chronic heart pump failure.

Due to rapid implementation of research findings by primary broiler breeders in selection programs, the numbers around those direct losses are no longer as high today. Olkowski believes, though, that hidden losses caused by subclinical or underlying, non-visible heart problems may be a more significant problem because of the additional performance and health impacts they create.

“There is some correlation between insufficiency of heart pump function and growth,” he said. “The best performing chickens have excellent hearts.”

According to Olkowski, literature suggests insufficiency of heart pump function as a predisposing factor for other conditions, like skeletal problems associated with bone weakness, skin conditions and muscle necrosis that science has been trying to solve for years.

“Recent research from the U.S. did correlate hypoxia – low tissue oxygen levels – with general breast muscle myopathies that include white striping and woody breast, so there might be more to heart failure than just death of the bird,” he noted.

New approach

Researchers have yet to find a treatment that is both effective and practical, although diet and environmental conditions like interior barn temperature have been known to have some positive impacts.

This is largely due to insufficient knowledge about the true underlying causes of heart failure, which led Olkowski to his latest research study, conducted with the help of the Canadian Light Source synchrotron at the University of Saskatchewan, that involved taking a closer look at the proteins in the hearts of broilers.

He examined samples of hearts taken from Leghorns, clinically normal broilers whose diets were restricted, broilers with subclinical heart issues fed ad libidum or free-choice and broilers with classic symptoms of heart failure who were also given an unlimited diet.

“I’ve never seen heart failure in Leghorns, so they are an excellent model of normal heart health,” he said. “It’s also a well-known phenomenon that when you restrict broilers to only 70 per cent of their ad libidum food intake, you can practically eliminate all problems of heart failure.”

The synchrotron scans showed pristine heart protein conformation in Leghorns, with some slight changes in the broilers on the restricted diet, and much more dramatic changes in the subclinical and clinical cases.

What this means, he noted, is that heart failure in broilers is associated with conformational changes, when misfolded and damaged proteins build up in the hearts of affected birds. And they are controllable by dietary restriction, he added.

Another important observation is that these are heritable changes associated with problems of gene expression and regulation, so they could potentially be controlled in the future through epigenetic intervention – a switching on or off of specific genes.

This latest project involving the Canadian Light Source was funded by Poultry Industry Council and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Print this page