Troubleshooting Water

Kristy Nudds

Features Business & Policy Trade a professor and extension specialist with the University of Arkansas Center for Poultry Excellence. Poultry Production Production they often turn to water expert Dr. Susan Watkins When broiler growers in the U.S. experience poor performance despite good management (and absence of disease)Some tips and guidelines on how to ensure quality and quanity

Dr. Watkins says the best way to know if you have something in your waterline is to go looking for it.

Dr. Watkins says the best way to know if you have something in your waterline is to go looking for it.

When broiler growers in the U.S. experience poor performance despite good management (and absence of disease), they often turn to water expert Dr. Susan Watkins, a professor and extension specialist with the University of Arkansas Center for Poultry Excellence.

She gets numerous “Dear Dr. Watkins” letters outlining performance issues where an issue with the water could very well be the causative factor. But she said that water is such a wide-open topic, it’s important to know how to identify the problem.

She gets numerous inquiries from growers and poultry companies who suspect they may have a water problem when they’ve examined their operation and are at a loss as to the cause of performance issues. “Could it be the water?” is the question directed at Dr. Watkins. She says the answer is always “absolutely it could be – but water is such a wide-open topic, it’s important to know how to identify if it’s the problem.”

To do this, she says start by evaluating and categorizing the symptoms. She says there are two key areas to consider – health challenges and water availability. “If we are witnessing health symptoms, then it’s likely a water quality problem and we suspect contamination, whether it is microbial, something arising naturally in the water, or even something we are adding.” But if there are no obvious health symptoms, the birds look good and livability is fine (even great), “then we have to suspect water consumption issues – they don’t have enough, there are restriction points, or they don’t like it,” she says.

The water poultry drink is the “perfect carrier” of health challenges, she says. Drinking systems are an ideal place for bacteria, viruses, protozoa, roundworms and other infectious agents to grow and multiply, because the water is slow moving, they offer many hiding places and pinch points, and we add substances to the water that help feed the microbes.

She cautions against assuming that water that is clear visually is of good quality. In presentations to industry, she shows a photo of three water samples – one clear, one that is obviously very dirty (you cannot see through it) and one that has what looks like it contains some organic matter but is, for the most part, clear. The sample with the least amount of microbial contamination? The one that was visually the dirtiest.

She also cautions against thinking that your water supply will not change. Even if you have had your water source tested, events such as droughts or floods can change the dynamics of the supply. She says growers must also consider factors that could affect quality such as if there is chemical storage nearby, and the type of rock and soil the water is passing through.

“There will always be something dissolved in the water, the question is, what’s in it today,” she says.

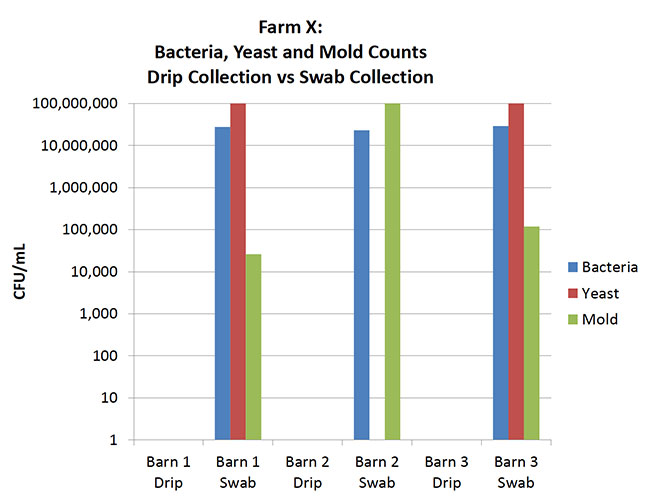

She suggests growers go looking for a possible contamination problem by taking swab samples at the water source and at the end of the water lines. To do this, insert a clean sponge, and swab the line 8-10 centimetres from the opening. Then return the sponge into 25 millilitres of sterile water or BPD and have the sample tested for yeast, mould and bacteria.

This method is far more effective than the traditional method of drip sampling, she says. Her research data shows that on many farms, drip samples can give a false sense of security. Often when drip samples indicate no contamination problems, a swab sample will show a very different picture (see chart on page 42).

|

| Comparison of mould, bacteria and fungus counts vs. sampling method. |

According to Dr Watkins, the key for success with water quality is a good sanitization program. “There are some wonderful products out there, but it is essential that you use them right.”

Concentration of the product used, and perhaps most importantly the exposure time of the product, is critical for sanitation. For example, tests by the University of Arkansas using a 3% bleach solution found that, even after four hours, there were still bacteria in the water at almost 1,000 cfu/litre, and this had come down little after 24 hours.

Monitoring is also crucial, both pre- and post-cleaning, to provide proof of effectiveness. “I see a lot of weaknesses where people say they are doing something, but there is no verification of it,” she says. Medicators can malfunction and if you miss it, you will get problems, she says.

Biofilms will always be a challenge, no matter what system or product is being used. Nasty microbes such as streptococcus, pseudomonas and E. coli thrive in biofilm so cleaning the lines properly is essential. Chlorine has been the go-to product for many years, says Watkins, and is a great sanitizer. But getting the pH level of the water is critical, because it will determine whether or not the efficacy of the chlorine.

Although chlorine works well, Watkins questions whether or not current cleaning programs are creating “superbugs” because contaminants may becoming resistant.

In the U.S. more broiler growers are turning to hydrogen peroxide as a daily sanitizer. Stabilized products give the best results and need to be delivered at 25-50ppm residual in drinking water.

Chlorine dioxide is also gaining popularity, produced by taking sodium chloride activated with an acid. The product has a number of advantages, including that it is pH insensitive and is more selective than hydrogen peroxide, targeting pathogens even at low dose rates. But it has to be activated properly, requiring correct pH levels and enough contact time.

Watkins is also “cautiously optimistic” about new water sanitation technology that uses ultra-violet light to infuse electrolyzed air into water, disinfecting it via a process called advanced oxidation. She thinks it may be helpful for sanitizing well heads and holding tanks, and is currently testing the technology.

As well as choosing the right product, poultry producers should pay close attention to their water delivery.

Watkins says growers need to understand the entire water system, and do an inventory. How many drinkers do you have? How long is the system? What are the distribution lines made out of? Do you have any dead end lines? How far is the distribution from the source to the barns? She notes that despite thorough cleaning of the lines in the barn, if you miss the distribution lines, “problems will keep coming back.”

Routine checking of injectors is also key. Running a gallon of water through it is not sufficient – she says you need to run twenty to thirty gallons through, to allow the injector to get up and running and ensure you’re getting the proper dosage to the birds.

WATER QUANTITY

Research by the University of Arkansas shows that, compared with 10 years ago, broilers are now drinking 38 per cent more water in the first seven days of life, and 16 per cent by the time they reach slaughter weight – equivalent to 15 gallons more water. Ensuring they get enough is key. “You must be sure you are not creating restriction points.” Water lines must be of a suitable diameter to deliver the required volume at peak demand times, otherwise birds will fail to put on sufficient weight, will have higher mortality and layers and broiler breeder will have reduced egg numbers.

If pressure reducers are in place, these must be checked to ensure they are not becoming clogged. Since chlorine can harden regulator seals, these should be checked, and drinker flow rates should also be monitored.

Water temperature is also important, she says. Day-old chicks like cool or room-temperature water, but will shy away from warm water, and this can affect weight gain.

Since water can literally make or break an operation, Watkins stresses that determining what factors may be affecting quality or quantity needs to be constantly monitored and fixed so that chronic problems can be avoided.

This article is based on presentations given by Dr. Susan Watkins at the 2014 Poultry Service Industry Workshop and the 2015 Western Poultry Conference.

TOP SANITATION TIPS

Do a total bacterial plate count to identify contaminants

- Use the right concentration and exposure time of product

- Clean everything, including storage tanks and

- distribution lines

- Follow cleaning with a sanitizer that birds can drink

- Swab the water lines regularly to monitor

- Sanitize between flocks

Print this page