Finding a Niche

By David Schmidt

Features Bird Management Production Organic and specialty chicken production Poultry Production ProductionOranya Farms produces the majority of specialty birds for the Canadian market and the bulk of B.C.’s organic chicken

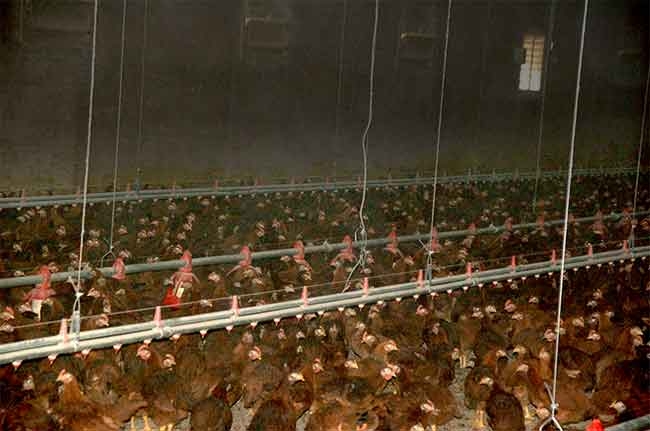

Oranya Farms is building an additional 10 two-storey buildings over the next two years to accommodate its expansion in organic and specialty birds

Oranya Farms is building an additional 10 two-storey buildings over the next two years to accommodate its expansion in organic and specialty birds

Organic and specialty chicken production may only represent a small fraction of Canadian chicken production, but it’s big business at British Columbia’s Oranya Farms.

Corry Spitters and his sons Jeffrey and Jordan have over 50 barns (floors) and are building 10 more.

“We now have about 250,000 birds in production at any given time,” they say.

Oranya produces Taiwanese chicken and Silkies on side-by-side farms in Aldergrove and organic chicken on an ever-expanding farm in Abbotsford.

“We grow about 80 per cent of the Silkies and Taiwanese chicken for the Canadian market.”

Each flock of Silkies (so named because of their snow white soft silk-like feathers which, ironically, cover a jet-black skin) is about 24,000 birds and takes 120 days to reach maturity.

“Silkies eat very little,” the Spitters explain. “We supplement the automatic feeders with paper feed to encourage them to eat.”

They are also not very good at converting what little they eat. A good Silkie feed conversion ratio is only 3.6-4.2:1 (3.6 kgs of feed produces 1 kg of bird weight), less than half the 1.5 conversion ratio for conventional broilers. As a result, Silkies are mostly skin and bone, weighing only 1.2-1.3 kgs when shipped. They are, however, very flavourful, and used to make a chicken soup highly prized at Chinese weddings and festivals.

The Taiwanese chickens (TCs) are also destined for the ethnic Chinese market, but as a meat bird. Shipped at 78 days, their meat is more yellow than conventional broilers. Marigold and other ingredients are added to the pelletized feed to enhance both colour and flavour.

“The meat takes on the flavour of what the birds eat,” Corry notes.

Breeders are trying to introduce some broiler genetics into the TCs so they grow faster but that is fraught with danger as it reduces the flavour – the TCs primary selling point.

Oranya has up to 32 flocks of TCs and Silkies on the go at any given time, but that pales compared to their organic chicken production.

“We produce 65-70 per cent of the organic chicken in B.C.,” Corry says, noting the farm ships out about 50,000 birds each week. The chicken is grown on demand for three B.C. processors: Lilydale (Sofina Foods), Sunrise Farms and Rossdown Natural Foods.

Although Silkies and TCs have a separate quota allocation, Oranya had to acquire mainstream quota to produce its organic chicken. The B.C. Chicken Marketing Board is grandfathering organic growers until July 2016, but what will happen after that is anyone’s guess. Oranya appealed the BCCMB’s rules governing quota allocations for organic chicken, but the B.C. Farm Industry Review Board has rejected the appeal, telling the two sides to negotiate a solution.

In the meantime, Oranya is moving ahead with expansion of their organic production. They already have 24 barns (each building is two storeys and counted as two barns) and are building another 10 over the next two years, each about 80X200 feet.

“Costco alone currently markets 25,000 kg/week of organic chicken in B.C. and Alberta and told us they expect to grow that market to 100,000 kgs,” Spitters says. “We intend to grow with them.”

When fully built out, the farm will be capable of producing 50,000 birds/week. Once market demand exceeds that, the Spitters intend to build another farm just like it.

To avoid paying the City of Abbotsford development cost charges of about $5,000/building, the farm built its own water treatment system. It uses two 26-foot-deep wells, producing up to 130 gallons/minute. The system includes state-of-the-art filtration to remove the 5 ppm iron content and soften the water, making it virtually pure.

“Our facility could service a town of 25,000,” Spitters says, noting the farm uses 1000-1200 cubic metres of

water/day.

At first glace, using double decker barns seems to go against organic standards. But the Spitters have found an innovative way to comply. They note the standards only require chicken to have outdoor access after three weeks old. Therefore the birds are raised on the upper floor for three weeks, then sent down a chute to the main floor which does have outdoor access, where they remain for the next seven weeks. This allows Oranya to reduce overall building footprints and helps minimize disease pressure, critical when organic standards forbid the use of antibiotics. Each barn is thoroughly cleaned after each flock and filled with fresh litter.

“Because birds get fresh litter partway through the growing cycles, it arrests pathogen buildup,” Spitters says.

Outdoor pastures are located between two barns and shared by the two flocks. Trees have been planted in the pastures and “toys” placed in the barns to meet the criteria for humane certification.

“Everything we do not only has to be sustainable but meet both organic and humane certification standards,” Spitters explains.

Oranya used to contract out moving and catching but now use their own crews. “When a bird is worth $10 or more, you can’t afford losses and the contractors weren’t as careful as we wanted them to be.”

By starting one flock while the previous one is still on its way out, the Spitters are able to grow up to 210 flocks per year.

Corry has been in the poultry equipment business since 1977 and lauds the cost and production benefits of using the latest technology. The Spitters use LED lighting in all barns and are the first producers in Canada to start using a SKOV system to manage feeding and ventilation.

“Our older system works on set points,” Corry explains. Vents are opened and closed and fans turned on and off based on specific climate settings.

The SKOV system “is a smart algorithm. It works on anticipation.” It uses current and historical data to predict conditions and manages the barns accordingly. Not only can everything be monitored remotely by smartphone, but the system sends out alerts when it detects an issue. It also monitors load cells on each of the feed bins using the data to communicate with the supplier when feed is required.

“We monitor everything and can sample a lot faster than most growers,” Corry says. “We can see instantly when a flock isn’t performing.”

Print this page