Pest Control: Hitting When It Counts

Kristy Nudds

Features Bird Management ProductionFly parasites target flies right at the source

Fly parasites target flies right at the source and are an effective component of Integrated Pest Management

Virgil Unruh has a standing joke with his local post office. Every spring and fall, he has been receiving rather unusual packages from Ontario.

Virgil Unruh has a standing joke with his local post office. Every spring and fall, he has been receiving rather unusual packages from Ontario.

The packages contain live insects known as fly parasites. The Acme, Alta., farmer has used these beneficial bugs as part of his pest management program to control filth flies in his layer barns for the past three years. He’s had such success with the parasites that he doesn’t mind the giggles from the ladies at the post office.

“There isn’t much I brag about, but these bugs are definitely something to brag about,” he says.

Unruh says when he changed his operation over to free run commercial layers over three years ago, “I knew I was going to have a big fly problem.” And he did. The first flock of birds was placed in the fall and utilize long-term litter, which he says is mostly dry but has a few wet spots now and then. By spring, he had crawling, black walls due to flies.

“I looked into the pits and could see more trouble coming,” he says.

Spraying with a pesticide helped in the short term but Unruh knew the flies would just keep coming back.

That’s when he decided to give a biological solution a try. “I’ve never been much for the green hype. I’ve always thought, get a chemical and kill it, and be done with it. But I was getting desperate and willing to try anything,” he says.

He began using fly parasites that spring and has never looked back. “The flies aren’t just suppressed, they are controlled. The parasites do a phenomenal job,” he says.

Essentially, fly parasites are a form of biological pest management. They are a “good” insect that is used to control a “bad” insect.

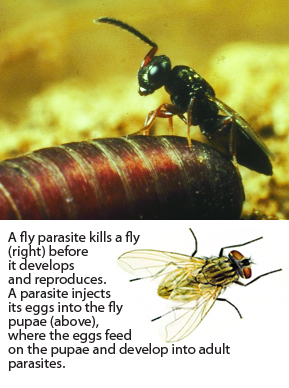

The parasites resemble tiny wasps (about the size of a flea) and their life cycle is dependent upon species of flies that are normally present in animal manure, decaying feed, hay, and garbage. They are completely harmless to humans and other animals and they can only survive by attacking the immature pupal stage of flies.

Fly parasites instinctively search for fly pupae, the stage of a fly’s development where it is going through metamorphosis (changing from a larva to a mature fly) and are encased in a hard shell. The female fly parasite has a special appendage called an ovipositor that enables her to puncture a hole through this hard shell and inject her eggs inside. These eggs soon hatch into larvae of their own and feed on the fly pupa as they grow.

Effectively, fly parasite larvae eat fly pupae from the inside out before the pupae can develop into adult flies. The fly parasites then perform their own development and emerge as adults, ready to attack more fly pupae.

Frank Marchetti, general manager of Bugs for Bugs, a natural pest management company that offers these fly parasites, says that this is the “real beauty of the program.”

“Fly parasites deal with the problem at the root cause,” he says. “They don’t wait until you have all kinds of flies and then you have to target the adult phase, like chemical pesticides do.”

Marchetti says that taking just a chemical approach doesn’t always take care of the problem. Pesticides can give a good, quick knockdown in the fly population, but it doesn’t address the fact that within the manure exists overlapping generations of flies in various stages of development. In a few days or weeks, a barn can be covered in flies once more.

“If you deal with the flies where they are breeding so they don’t even become an adult, then you’re getting to the root cause of the problem,” he says.

This approach can be particularly helpful in the summer months, when higher temperatures mean quicker development cycles for filth flies. Generations of flies can reproduce so quickly that a generation can be completed in a week or less. Marchetti says that filth flies can lay up to 500 eggs per female, an amount 10 times greater than other insects, including fly parasites.

The fly parasites are indigenous North American species and are not genetically manipulated to be aggressive or wreak ecological havoc, says Marchetti.

They are mass produced in an insec-tory, or “bug factory” under optimal growing conditions. They are provided with fly pupae and they are collected and shipped before they become adults and emerge from the fly pupae via Canada Post’s Xpresspost™. The pupae are mixed with wood shavings to help absorb excess moisture from respiration (and to act as a carrier material) in packages that have one side made of Tyvek, a breathable strong paper, and a see-through plastic on the other side.

Marchetti says that he ships packages containing 25,000 parasites. When customers receive the box, they can see inside through the plastic and when they start to see the tiny wasp-like parasites crawling around, it’s time to sprinkle them out of the package where flies are breeding in the barn, normally near manure or waste build-up.

Marchetti is an advocate of using an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach to pest control (see sidebar page 28). He says that when farmers have a pest problem, they should use all of the tools available to them to get the best results.

Fly parasites are a biological control option and offer the benefit of using fewer chemical controls, which can have harsh side-effects, says Marchetti. “Chemicals also act on non-target species and if we can use less of them, then why not try?” he says.

To ease chemical use and utilize the full potential of fly parasites, Marchetti says that the key to success is taking an inundative approach and overpowering the filth flies.

To do this, the fly parasites must be introduced before the flies get out of control. When a new flock comes into the barn and the first layer of manure gets tacky and flies start to emerge, that’s when fly parasites should be used. Parasites are introduced every two weeks through susceptible periods (normally begins in spring) and continue through to the fall, but it’s up to the individual operation, he says.

“By doing these repeated introductions, flies never get the chance to get the upper hand,” he says.

It’s sheer numbers that make this work. Flies have considerable reproductive advantages over the parasites, so doing repeated introductions allows many, many more parasites to be present. This will allow the parasites to control and overcome the reproductive advantages of the flies.

Virgil Unruh says for his operation, he introduces the parasites every two weeks for four weeks in early spring and again in the fall. “The first year I used the parasites, I probably had two flies in the barn all summer, about a dozen the following year and have only seen two so far this year,” he says. He uses sticky strips in his service area to comply with HACCP and says he knows that if flies are on his farm, they aren’t coming from his barn.

Unruh and many of Marchetti’s customers don’t have to use chemical sprays anymore. Marchetti’s customers also include dairy and horse farms and depending on the set-up, some find that they have to use spray every four to six weeks in addition to the parasites to combat flies, but that “they don’t see it as a failure,” he says. “They are quite happy with using 20 per cent of what they were in the past.”

Just how many fly parasites are needed is a bit of grey area, says Marchetti. “A lot of it depends on an individual farm’s manure management and other IPM tactics employed on the farm,” he says. Generally, he recommends two fly parasites per bird, except for the first introduction, where it should be doubled.

If flies have already become a problem in the barn, he recommends doing some sprays and then following with a heavy dosing of parasites, to give them a chance to catch up.

Other components of IPM should also be used to bring the populations down.

For more information on fly parasites and IPM, Frank Marchetti can be reached at 519-836-8166, e-mail: frank@bugsforbugs.ca n

Print this page