CEMA Searching For Agreement

Jim Knisley

Features 100th anniversary Key Developments Business/PolicyMay 1999

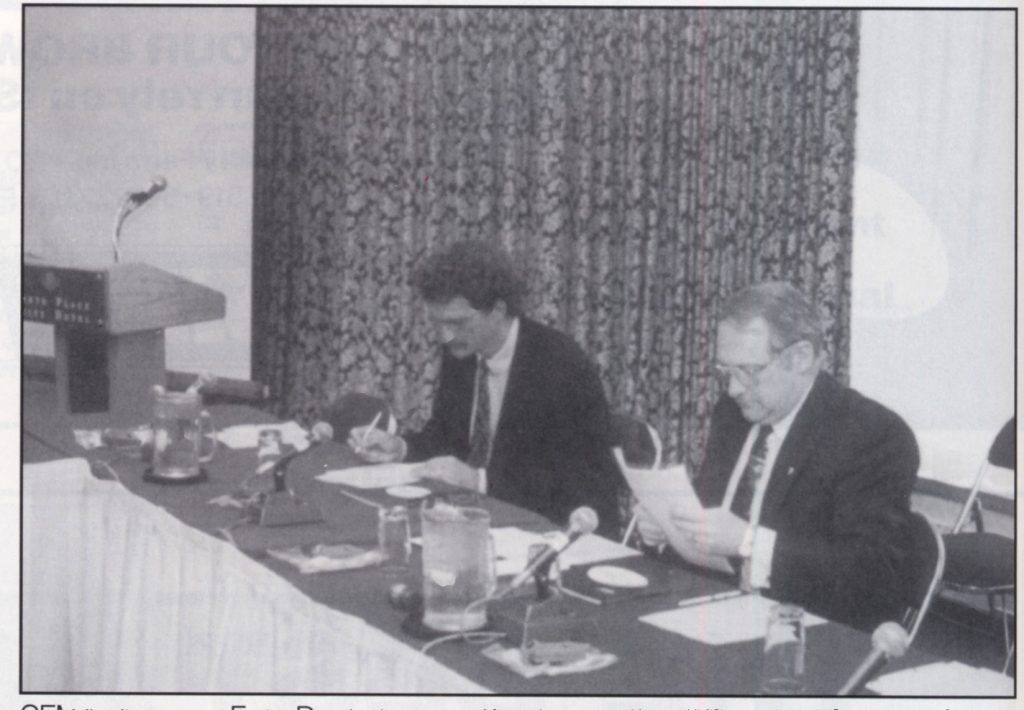

CEMA Chairman Felix Destryker and Chief Executive Officer Neil Currie at the national agency’s annual meeting in Ottawa.

CEMA Chairman Felix Destryker and Chief Executive Officer Neil Currie at the national agency’s annual meeting in Ottawa. The national egg production and allocation system has been so successful in increasing consumer demand that it has created a crisis that threatens the existence of the CEMA and the well being of Canada’s egg producers, CEMA chairman Felix Destryker said at the agency’s annual meeting in Ottawa.

“It is somewhat ironic, but the challenges we face are the result of our accomplishments,” he said at the March meeting.

The cooperative work of CEMA’s marketing team and the provincial boards has paid off and now agreement must be reached on how to share the market and the allocation of new production.

But agreement has been hard to find.

Last year, directors and staff worked long and hard to find a way to resolve the issue. A discussion paper was circulated in January. That was followed by meetings through the summer.

“Directors repeatedly went through exhaustive debates. We had to take into account everyone’s point of view. The views were many and they were complex. In some cases, they reflected fundamental questions about the philosophy of our system and how it ought to function,” he said.

In November a package was approved by CEMA’s board that would meet growing domestic needs.

It included 430,000 new layers to be allocated across the country on a regional basis, a uniform national levy and an increase in the buy back price. Ontario and Quebec each got 35 per cent of the allocation–150,000 new layers each. Other provinces were allocated between 8.5 per cent of the total for British Columbia and 0.4 per cent for PEI.

To meet the processors’ export needs Ontario and Manitoba were each allocated 200,000 quota units for 1999. The agency also had to create an export market development quota to accommodate new ventures between processors and individual producers. The pressure from government to open the door to such new ventures was enormous, he said.

But CEMA was concerned that such private agreements “could disrupt markets if they were not properly managed within the Canadian egg marketing system.” After producers, the processors and the provincial government agreed to security measures ensuring the project would not disrupt markets, up to 500,000 units were allocated to Manitoba.

When CEMA directors reached this agreement last November, DeStryker said: “ I had a great sense of relief.”

“I dreaded a looming egg war and my fear was erased when an agreement was reached.”

The agreement wasn’t perfect and plans were to continue negotiations.

“But I took some satisfaction from the fact that we had a new framework in place to allow expansion and increased prosperity,” he said.

But the satisfaction of achieving a breakthrough was short lived.

In January, the Quebec board withheld payments to the Pooled Income Fund. Quebec had given notice in July 1998 that they would withhold payments beginning in January 1999 if their concerns over allocations weren’t resolved.

“There is very clearly a disconnect between, on the one hand, what was negotiated and agreed to, or at least what we, in good faith thought was agreed to, and what, on the other hand happened last January.”

Now, Ontario has said it will have no choice but to discontinue financing the national pool if Quebec’s concerns are not addressed, he said.

“I sometimes get the impression that some of us imagine the overall egg marketing system in Canada to be some kind of tool with or without options that can be borrowed for a period of time to better suit each user,” he said.

“I do not think our egg producers, and maybe even those much closer to the scene, realize just how serious the situation is and to what degree the cannibalization of each others’ markets is imminent. It is an ugly scenario,” he said.

Dealing with the industrial products program is the most complex challenge facing CEMA and the provincial boards. But this program lies at the heart of the supply management system.

“It prevents provinces and regions from cannibalizing each other’s markets in an effort to sell their products. And preventing cannibalization in breaking eggs is the key to preventing cannibalization in table eggs.”

“If we lose agreement in the national industrial products program, we lose agreement on the heart of supply management,” he said.

There is the danger of a domino effect of competition among provinces and regions leading to the loss of price supports.

“The chicken and egg wars of the late 1960s and early 1970s underline that this is an ugly yet realistic scenario,” he said.

The way to avoid that scenario is to cooperate and communicate.

“We look after the interests of producers most effectively when the provincial boards put forth their best cooperative efforts within the national agency,” he said.

But cooperation alone won’t provide all the answers. Communication is the other key.

“We must escape from this predicament of not understanding each other,” he said.

To help resolve the communications problem CEMA has hired RANA International, a firm specializing in communication and conflict resolution.

The firm has already met each of the provincial boards and will work through the spring to assist the agency and its members.

“I am convinced they can help us by providing us with the necessary tools to avoid these cynical crises which make our lives unbearable and jeopardize our future,” he said.

Print this page