The story of a Kentucky super-brand: Kentucky Fried Chicken

By John Y. Brown Jr.

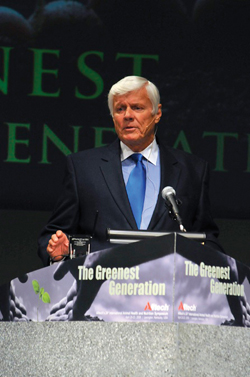

Features New Technology ProductionThe following is John Y.

Brown Jr.'s speech to the 1,700 delegates at Alltech's 24th Annual

International Health and Nutrition Symposium on April 23, 2008.

In it he discusses buying Kentucky Fried Chicken from "Colonel" Harlan

Sanders, growing the business, and creating a super-brand.

The following is John Y.

The following is John Y.

Brown Jr.'s speech to the 1,700 delegates at Alltech's 24th Annual

International Health and Nutrition Symposium on April 23, 2008.

In it he discusses buying Kentucky Fried Chicken from "Colonel" Harlan

Sanders, growing the business, and creating a super-brand.

The dream – A super-brand

This is exciting for me to be able to tell the story of Kentucky Fried Chicken because it was truly the great American dream, not only about the life of the Colonel and how he started, but also the opportunity I had as a young man.

Colonel Sanders was 65 years of age when he started Kentucky Fried Chicken. He was out of money and Highway 75, which went around his restaurant and filling station, had moved. He had developed a little restaurant while perfecting a fried chicken recipe with 11 herbs and spices. He had developed a pressure cooker method of retaining the juices of chicken. He really had an unusual product.

I asked him what happened when he was 65. He said, "John, I just went out and did what I thought I could do better than anyone else in the world. That was fry chicken."

He got in the car with his wife and they travelled around the country in an old jalopy, pots and pans and seasoning in the trunk, knocking on restaurant doors and getting restaurateurs to taste his chicken. He'd get out of the car, go in, and fry some chicken. If they liked it, they would put in some money.

Over a period of time, he started wearing a white suit and a goatee. Imagine how bold to walk down the street in a white suit, goatee, and a mustache. We didn't know what to think of the Colonel. He had his picture on the side of his Cadillac. We didn't know what he was up to.

One time the Colonel was the witness in a court case. The opposing attorney asked him, "Colonel, will you tell the jury what war you fought in?" The Colonel said, "I didn't fight in any war." The attorney said, "Will you explain to the jury what that Colonel means before your name." The Colonel said, "It means about the same thing as that Honorable before your name. It doesn't mean a darn thing."

Here was an unusual entrepreneur to have the imagination to put chicken in a bucket and to use a logo of "finger-lickin' good." He had 17 employees and literally changed the eating habits of the world.

Today Kentucky Fried Chicken is in over 80 countries with $16 billion in sales last year in over 14,000 units. As Victor Hugo said, "This is truly an idea whose time has come."

I had an opportunity in 1964 when the Colonel called me about wanting me to be his real estate lawyer. I delayed meeting with him for four or five months because I thought the guy was a little bit strange and I didn't really know what he wanted.

Finally, one day when I had nothing else to do I stopped by to visit him. I was fascinated with the story of what he was doing. We didn't know we were in Kentucky. (As you know, a man is never a prophet in his own town.) Instead, he took me upstairs and started going through the files of these royalty checks. He had 600 little restaurants with his picture, featuring Kentucky Fried Chicken. He showed me where one would pay $300 a month, another $280, and another $500. I was fascinated. Right then and there, even though I was a practising attorney, I said I am going to find my home here.

That particular day the Colonel had an idea; he wanted to start a barbeque franchise. I said, "Colonel, I am your man." We did a joint venture. I had a right to open up what we called "Porky Pig." We had barrel furniture and a big fire furnace to cook the barbecue. I borrowed $16,000 from a finance person in Nashville named Jack Massey, who eventually became my partner. After we opened, we sold 80 per cent Kentucky Fried Chicken and 20 per cent barbecue. I knew then that I was in the wrong end of the right business.

Once we realized the dynamics of Kentucky Fried Chicken and its potential, we immediately approached the Colonel and made arrangements to buy him out for $2 million with $500,000 down, $1.5 million over six years at three per cent interest. I remember shortly after that he spoke to the Rotary Club about how he fleeced a couple of city slickers out of $2 million for his chicken recipe. But what an opportunity it was for us, because he had the basic ingredients.

I spent most of my time building the brand. Here was the only person in the world outside of the Pope who wore a white suit. He had the goatee and the mustache; he stood out under any and all circumstances.

Over the first three years, I was able to get him on 31 national TV shows, from Johnny Carson to What's My Line? They had never heard of him, didn't know who he was. He even danced on The Lawrence Welk Show. Any way to get the man in the white suit before the public. Every time we had him on a national show, sales would jump 10 per cent.

Every day we promoted the Colonel, whether he was in a parade or whether he was on the phone talking to the Des Moines Register or a radio station. We did nothing but promote the Colonel.

The first thing we did was to tell the story of his life. He was 74 years old. We didn't know how long he would live. But what a promotional opportunity he was.

Out of that effort, we grew so fast. We realized that some of the restaurants were doing 40 per cent of their sales in Kentucky Fried Chicken alone. So, why not create a store to sell only chicken? We were entrepreneurs, and we'd try anything. After all, if your leader wore a white suit, why can't you try something unusual?

So, in Florida, we opened what we called our first "take-home" and realized, "Gee, that's the business we should be in." Thereafter, in the next six years, we opened 3,500 of what we called take-homes with just chicken, and we got out of the restaurant business.

The Colonel had one-page contracts. We worked on the honour system. We got along fabulously with the franchisees. They were making money, and we were making money. We did not have to close a single store or deal with a single lawsuit. It was just one big family.

I remember when we went public. The New York Stock Exchange made history by inviting Colonel Sanders to the floor with all the brokers. You can imagine all the excitement the Colonel made on the floor the first day we opened our stock. Out in front of the New York Stock Exchange, we had a big truck giving away buckets of chicken. He was a promoter's delight because once you saw him, you remembered him.

One thing about a brand is that you have to build credibility and you have to build consistency. Today Kentucky Fried Chicken is the same as it was 45 years ago when the Colonel created it.

If there is anything I learned, it was that I didn't know anything. I listened to the Colonel. Of all the 10,000 employees, he knew more about his concept and his passion than all the employees combined. So we stuck with that concept – it's the same today, same products, same recipes, and even pretty much the same size of buildings. Most ideas don't endure for that period of time. People want to come in and change them.

Yet, today as a fast-food chain, Kentucky Fried Chicken is second in size only to McDonald's. Back in the 1960s, KFC was larger than McDonald's. It was the world's largest food service company.

In 1969, we had the opportunity to go overseas. We ended up being established in 57 foreign countries before we sold in 1971. I met a man by the name of Loy Westin, who worked in Lexington at IBM. He lied to me. He told me he spoke Japanese during the Korean War. I said, "That's perfect. We will send you to Japan, and you can open up." I gave him $100,000 and pots and pans and seasoning and sent him on his way. We signed a deal with Mitsubishi. (You had to have an investment in Japan at that time.) It took 30 minutes. The next time I saw Loy was when I was governor. I went to Japan; Loy had opened 800 stores. We didn't operate like McDonald’s; they did their research. I just said, "Build one, Loy. If it works, build two." He built a chain. And that is what franchising is all about. If you have a better idea, you just duplicate it time and time again.

Today Kentucky Fried Chicken is in China. And last year KFC made $375 million in China, twice what it made here in the United States. So, today 60 per cent of Kentucky Fried Chicken is sold overseas.

I have been very fortunate in my life to be closely associated with the two greatest brands that the world has ever known. One, of course, is Colonel Harlan Sanders. The other is Muhammad Ali. In fact, over the last 25 years, more people would recognize Muhammad Ali and Colonel Sanders than would recognize Ronald Reagan, both George Bushes, Clinton, and Oprah combined. And these two super-brands were developed right here in Kentucky.

I led the development of the KFC super-brand. And I think most of the things we did we did because we just didn't know any better. We didn't know we couldn't do them until we did them.

Even after three years, we all decided that old Brown needed to go to Harvard and learn how to run a business. So, I went up to see George P. Baker at the Harvard Business School. This is a true story. I asked him, "What can I learn? Do you have any summer programs?" Fortunately, I had lunch with 11 professors. They were asking about Kentucky Fried Chicken, and I had never read a balance sheet or PNL (profit and loss). I thought that to run IBM you had to be a genius or go to Harvard or Stanford. After about an hour, one of them asked, "Mr. Brown, how have your sales been?" I said, "Well, we've gone from about $3 million to a little over $100 million." I thought everybody did that. I didn't think it was anything extraordinary. "What about your profits?" he asked. I said, "Well, we've gone from about $300,000 to a little over $10 million pre-tax." My host just looked at me and smiled, "Mr. Brown, you go on back and keep doing whatever you are doing. Don't let us confuse you."

So, that was the first time I realized that there are no geniuses; there are no experts. Most everything that happens in life is a matter of selling.

In this room there are many great researchers from the fields you represent, who are so important in developing the future and the unknown potential of Alltech. However, understand one thing – nothing happens until the sale is made.

You take the brands of Colonel Sanders and Muhammad Ali. They say a brand is worth 10 times whatever the time and expense of advertising. Ali and the Colonel were very much alike. They separated themselves from the crowd. Can you imagine someone coming out on this stage and saying, "I am the greatest. I am going to change the world." And he did. Can you imagine a man in a white suit coming out and saying, "I've got a product for you and it's the best in the world." And it was. So, these two Kentuckians were the greatest showmen I have ever been exposed to. I don't know of any two personal brands that have had more impact worldwide.

Once you build a brand, the selling is so much easier because you have built the credibility, you have built the attachments, and you have built the emotional association. Some women like to say they have been to Saks or Neiman Marcus or you may be an athlete who likes to wear or use certain kinds of sporting gear. We all have an ego to be proud of what it is that we use. So, branding in the building of any company is essential.

Alltech – the new Kentucky super-brand

I think Alltech has unusual opportunities. I think public relations is probably the best vehicle, certainly the cheapest, to promote any product. You have limitless opportunities to promote all your different products because they have to do with health, with areas that are curious and pretty much unknown. What Pearse (Lyons) has planned for the state of Kentucky with his biofuel and what he is doing with feed for animals and for our crops and even getting into the whiskey business – he is covering the board. He is ready to run for governor. I am ready to support him. He can still run Alltech on the side. He has the key to unlock the potential of our great state. Our great state is sitting here, and we applaud and are excited about the opportunity to work with Pearse.

There are so many other important changes in the world. Today America is no longer a dominant marketplace. Today America doesn't have the richest person in the world; that person is in Mexico. The tallest building is in Taipei. The largest refinery is in India. The largest company and richest bank are in China. The 10 largest malls in the world are all outside the United States. We live in a different world today.

The Internet has taken over as a method of communication. My oldest son, 27 years of age, graduated from The Wharton School of Business. He developed a business called Entertainment Media Works whereby if you see an item on television, you can go to his website and buy it immediately. There are 23 national television shows signed up including American Idol. Now if you see this tie or that hat or pair of shoes or table on TV, it can be yours! The world is changing!

What I see about Alltech at your symposium is that you are ahead of the curve. And you have the greatest salesman in Pearse Lyons. Remember, it all boils down to selling. Nothing happens until a sale is made.

I speak to you because I am an entrepreneur. America has been built on entrepreneurism. Eighty per cent of all jobs in America come from small business. This development has happened in the last 30 years. It comes from small ideas. Big companies are usually not capable of starting new businesses. I know, in my restaurant business that there was only one chain that was ever developed by a big company. It takes the entrepreneurial spirit that Alltech has to develop the future.

I had the chance six years ago to be a keynote speaker in Great Britain in a presentation given by the U.S. Ambassador on entrepreneurism. I was surprised to find out that in that part of the world they don't believe in being an entrepreneur. I asked the cab driver going to Wimbledon, "Why are they against you owning your own business?" He said, "To tell you the truth, it's just that you are embarrassed. If you fail, they don't allow failure. I have six cabs, but I can't tell anybody." One thing about America – we don't ever fail as entrepreneurs. We just change until we get it right.

When I look at Alltech, I see a company with $400 million in sales now, but, if my instincts are right, someday it will be $4 billion and maybe even $40 billion. The sky is the limit. It reminds me so much of my Kentucky Fried Chicken days where everyone is so excited and so enthusiastic and so confident about the future. It was Ralph Waldo Emerson who said, "Nothing great in life is ever achieved without enthusiasm."

Alltech people are thinking about building and being creative, not keeping the score but making the score. Pearse said on Monday, "Don't worry about getting it right. Just get it going." You know, winners make it happen and losers wait for it to happen. So, with you, all I can say is go to the front and increase your lead.

I would like to close with a poem written by the English poet Everett Martin:

"Oh, how great it is to stand in youth and dream your dreams before the stars. A greater thing yet is to fit life through and find at the end that your dream is true."

Print this page